5 Minutes

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have uncovered a surprising molecular partnership that helps protect chromosome ends. Their discovery links a well-known DNA-binding protein to telomerase activity, shedding light on why some patients develop unexplained, life-threatening short-telomere disorders.

Why telomeres matter and where the mystery began

Telomeres are repetitive DNA-protein caps that sit at the ends of chromosomes and prevent the genome from fraying. Each time a cell divides, telomeres shorten slightly, a normal part of aging. When telomeres shrink too far or are not properly maintained, DNA becomes unstable and cells can stop dividing or die — processes that underlie premature aging syndromes and several severe blood disorders.

Researchers have long linked defective telomerase, the enzyme that rebuilds telomeres, to clinical conditions such as aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. But in many patients with very short telomeres, no mutation in telomerase itself could explain the disease. That gap in understanding motivated the new study.

How an unexpected partner came into focus

Led by professor Ci Ji Lim, the UW–Madison team used AlphaFold, a machine-learning tool for predicting protein structures and interactions, to search for proteins that might interact with human telomerase. Their computational screens flagged replication protein A, or RPA — a ubiquitous single-stranded DNA-binding protein best known for roles in DNA replication and repair — as a plausible telomerase partner.

From model to molecule: experimental validation

Guided by AlphaFold predictions, graduate student Sourav Agrawal, research scientist Xiuhua Lin and postdoctoral researcher Vivek Susvirkar performed biochemical experiments that confirmed the computational hypothesis. In human cells, RPA was required to stimulate telomerase activity and help maintain telomere length. In other words, RPA not only binds single-stranded DNA during replication and repair, it also helps telomerase do its job on chromosome ends.

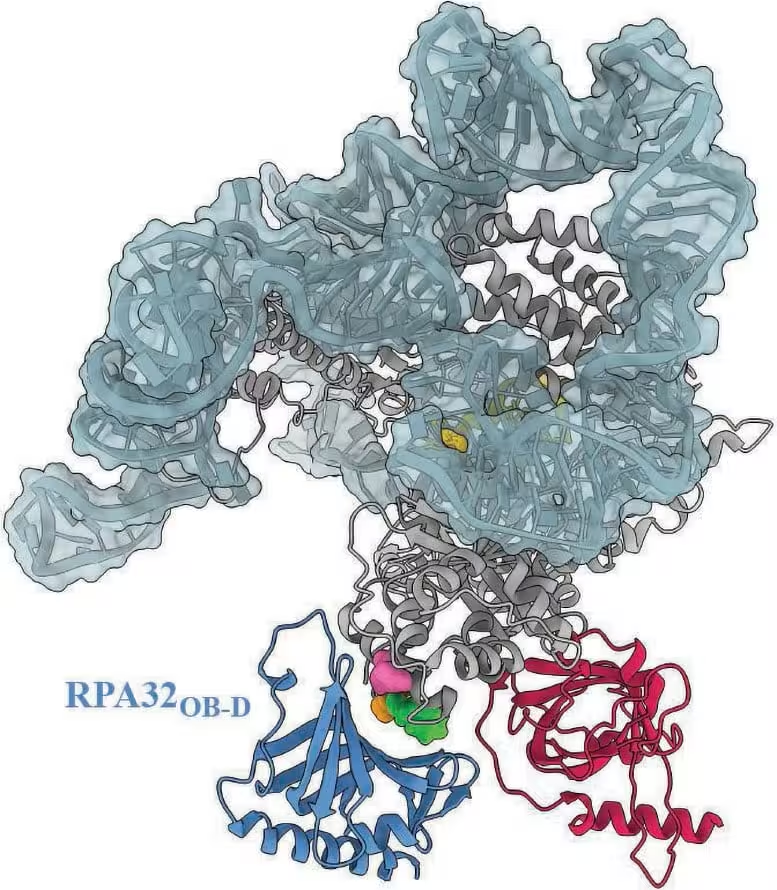

A model of the human telomerase complex highlights where RPA is predicted to dock. Three structural variants of telomerase that have been linked to patients with various diseases fall within this docking zone, suggesting that these variants could inhibit RPA’s interaction with telomerase. Credit: Ci Ji Lim

Clinical implications: a missing explanation for short-telomere diseases

Lim emphasized the clinical importance: 'This line of research goes beyond a biochemical understanding of a molecular process. It deepens clinical understanding of telomere diseases.' The team showed that some disease-associated telomerase variants fall within the predicted RPA docking site. That spatial overlap suggests those variants may block RPA from stimulating telomerase, producing the unexplained short-telomere phenotype clinicians have seen in certain patients.

The discovery gives doctors and geneticists a new target when screening patients with unexplained telomere shortening. Instead of looking only for telomerase mutations, clinicians can now test whether a patient carries variants that disrupt the RPA–telomerase interaction, potentially revealing causes for conditions that were previously mysteries.

Global interest and next steps for testing

The work has already drawn international attention. Lim reports inquiries from clinicians and researchers in countries including France, Israel and Australia who want biochemical tests to evaluate whether their patients’ mutations affect RPA binding or telomerase stimulation.

'There are some patients with shortened telomere disorders that couldn't be explained with our previous body of knowledge,' Lim said. 'Now we have an answer to the underlying cause of some of these short telomere disease mutations: it is a result of RPA not being able to stimulate telomerase.' With biochemical assays, the team can evaluate patient variants and give physicians insights into likely mechanisms, prognosis and potential therapeutic angles.

Tools and technologies that made this possible

The study showcases how modern structural prediction tools like AlphaFold can guide wet-lab experiments. By prioritizing candidate interactions computationally, the researchers narrowed the search space and then validated RPA's role through classical biochemical assays. This combined approach accelerates the path from hypothesis to clinically relevant insight and highlights the role of interdisciplinary collaboration between biochemistry and computational structural biology.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morales, a molecular geneticist unaffiliated with the study, noted: 'Linking RPA to telomerase opens a new layer of regulation for telomere maintenance. Clinically, this helps explain a subset of patients with idiopathic telomere shortening. From a therapeutic perspective, restoring or mimicking RPA's stimulation of telomerase could be an exciting avenue to explore.'

As researchers expand testing and screen patient variants for effects on RPA interaction, we may see faster diagnosis for families affected by short-telomere syndromes and, in time, molecularly informed treatment strategies.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

mechbyte

hmm, sounds promising but is it reproducible across cohorts? blocking RPA is plausible, yet we need more patient functional data and assays before jumping to therapy ideas

bioNix

wow, AlphaFold actually pointed to RPA helping telomerase. Didn't see that coming. Huge for unexplained telomere cases, but how many patients? curious…

Leave a Comment