7 Minutes

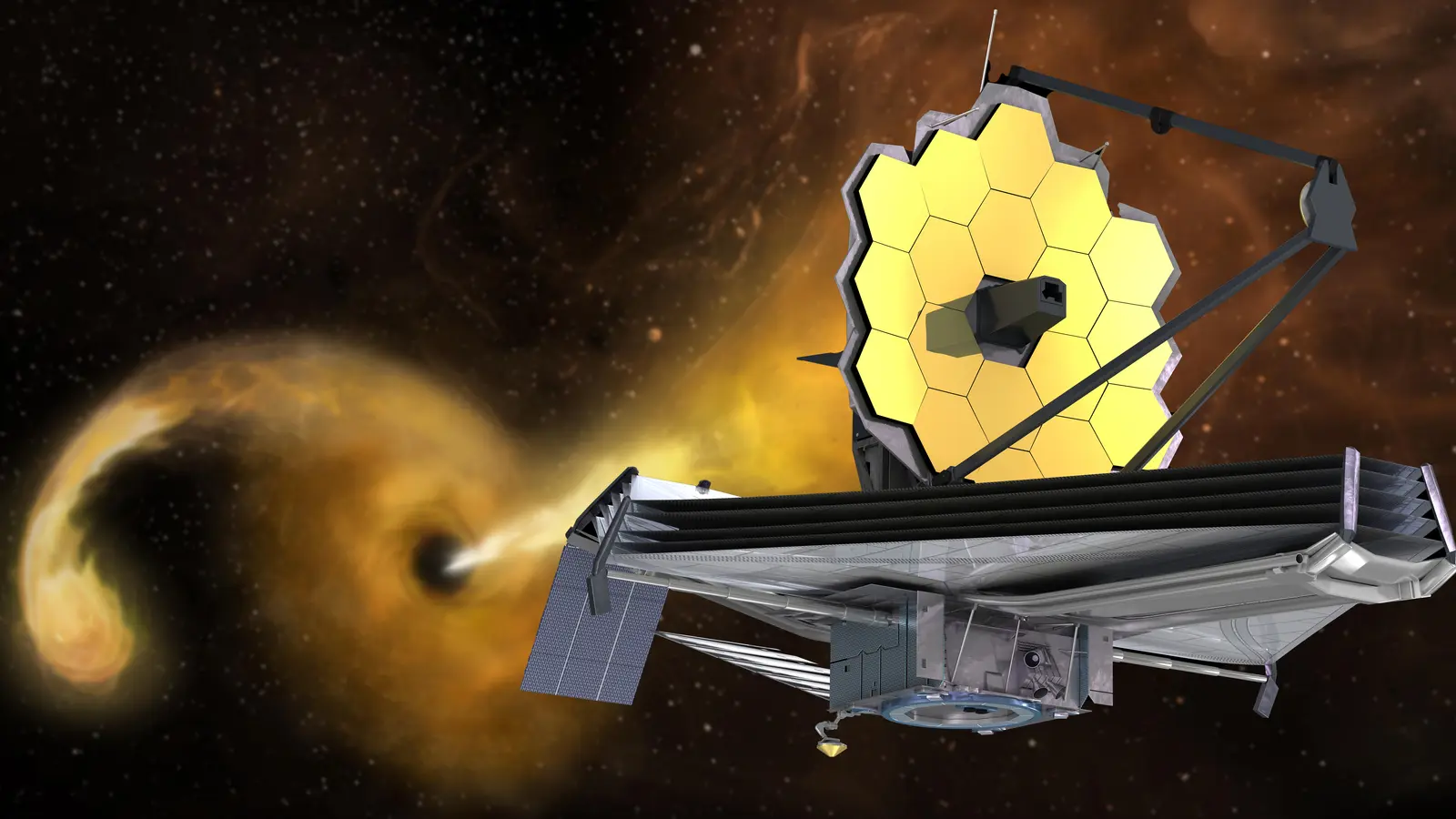

The James Webb Space Telescope has produced the first three-dimensional map of an exoplanet atmosphere, revealing blazing regions where water molecules are torn apart by extreme heat. Researchers used spectroscopic eclipse mapping to chart temperature and chemical differences across WASP-18b, an ultra-hot Jupiter whose dayside reaches nearly 5,000°F.

A 3D First: Mapping an Ultra-Hot Jupiter

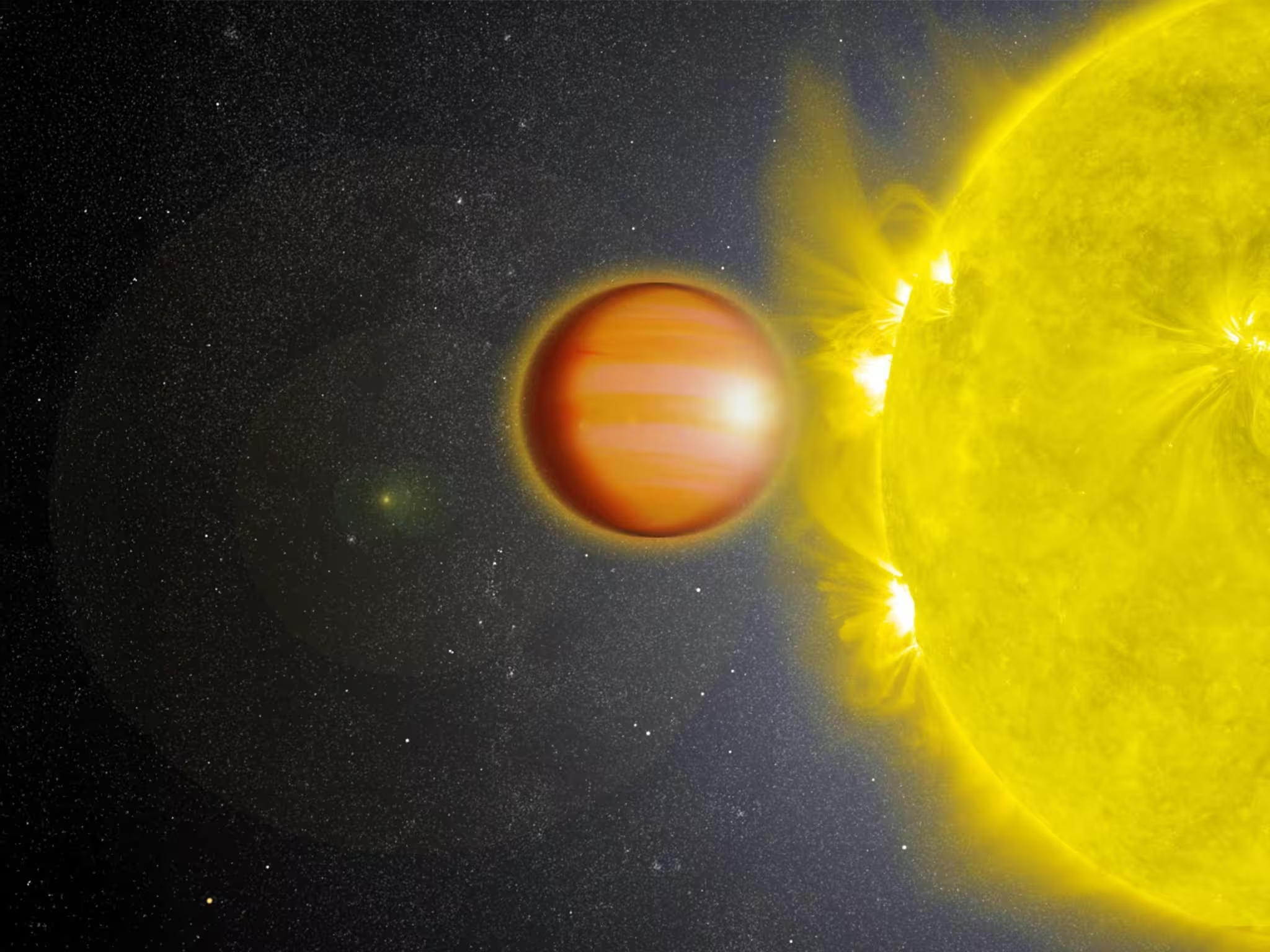

WASP-18b is a testbed for new observational techniques. Located roughly 400 light-years from Earth, this gas giant is about ten times the mass of Jupiter and completes an orbit in just 23 hours. Tidally locked to its host star, one hemisphere endures constant stellar irradiation while the other basks in near-perpetual night. Those extremes make WASP-18b a powerful infrared beacon for JWST and ideal for exploring atmospheric physics at temperatures that can exceed ~5,000°F (around 2,760°C).

Led by teams at the University of Maryland and Cornell University, the study (published in Nature Astronomy, October 28, 2025) expands a 2023 two-dimensional brightness map into a full three-dimensional reconstruction that spans latitude, longitude and altitude. The crucial advance comes from spectroscopic eclipse mapping: measuring tiny changes in starlight as the planet slips behind its star across multiple wavelengths, then converting those signals into a layered temperature-and-chemistry model.

How Eclipse Mapping Peels Back the Layers

Eclipse mapping exploits the fact that different wavelengths of light probe different atmospheric depths. Instruments like JWST’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) can record spectra across a range of wavelengths while the planet is eclipsed. As portions of the dayside are sequentially hidden from view, the subtle drop in flux at each wavelength encodes the brightness distribution on the planet at that specific atmospheric depth.

"This technique is really the only one that can probe all three dimensions at once: latitude, longitude and altitude," said Megan Weiner Mansfield, co-lead author and assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland. "This gives us a higher level of detail than we’ve ever had to study these celestial bodies."

Ryan Challener, the paper’s co-lead author at Cornell, added: "Eclipse mapping allows us to image exoplanets that we can’t see directly, because their host stars are too bright. With this telescope and this new technique, we can start to understand exoplanets along the same lines as our solar system neighbors."

A Planet Where Water Doesn't Survive

The 3D map reveals a concentrated, circular hot spot on the planet’s permanent dayside and a cooler annulus near the terminator (the day-night boundary). Importantly, spectral layers that are sensitive to water vapor show markedly lower water abundance in that hottest region than in the surrounding cooler zones. The interpretation is straightforward: at temperatures approaching a few thousand degrees Celsius, water molecules thermally dissociate into hydrogen and oxygen — effectively destroying water as a detectable molecule in the atmosphere.

"We’ve seen this happen on a population level, where you can see a cooler planet that has water and then a hotter planet that doesn’t have water," Weiner Mansfield explained. "But this is the first time we’ve seen this be broken across one planet instead. It’s one atmosphere, but we see cooler regions that have water and hotter regions where the water’s being broken apart. That had been predicted by theory, but it’s really exciting to actually see this with real observations."

Scientific Context and Methods

Ultra-hot Jupiters like WASP-18b occupy a regime where molecular dissociation, ionization and radiative processes strongly shape atmospheric structure. In addition to water dissociation, other molecules (for example, titanium oxide or vanadium oxide) and atomic species can become dominant absorbers at extreme temperatures, altering infrared emission patterns. The new 3D maps combine multi-wavelength eclipse data, atmospheric modeling and inversion techniques to assign temperatures to discrete latitude-longitude-altitude voxels, producing a volumetric view rather than a flat brightness map.

This approach complements other JWST methods such as transit spectroscopy (which probes limb composition) and phase-curve monitoring (which traces longitudinal heat transport). By resolving altitude as well as surface coordinates, spectroscopic eclipse mapping connects chemistry and dynamics: where heat is strongest, molecules break; where it’s cooler, chemistry is preserved.

What This Means for Exoplanet Science

- Proof of concept: The method demonstrates JWST’s capacity to produce 3D atmospheric diagnostics, opening pathways to study many hot Jupiters already known among the 6,000+ confirmed exoplanets.

- Chemistry and circulation: Maps like this reveal how stellar irradiation, winds and vertical mixing distribute heat and species across a planet, validating or challenging atmospheric circulation models.

- Comparative planetology: With more targets, astronomers can compare atmospheric breakdown across a range of temperatures and gravities, linking molecular survival to planetary properties.

- Beyond gas giants: Researchers hope to adapt the method to smaller, potentially rocky worlds; even for airless planets, eclipse mapping could trace surface temperature maps and hint at composition.

Expert Insight

Dr. Lena Ortiz, a fictional astrophysicist and atmospheric modeler at the Institute for Exoplanet Studies, commented: "Seeing water dissociate spatially across a single planet is a watershed moment. It confirms long-standing predictions from high-temperature chemistry and shows that JWST can separate vertical and horizontal signals that were previously blended. The next step is to apply these maps to a diverse sample — then we can begin to chart atmospheric evolution as a function of incident flux and planetary mass."

Future Prospects: Sharper Maps, Smaller Worlds

The research team notes that additional JWST observations will refine resolution and reduce uncertainties, enabling denser sampling of altitude layers and more precise chemical retrievals. As telescope time accumulates and mapping techniques improve, astronomers expect to produce 3D atmospheric atlases for dozens or even hundreds of transiting hot Jupiters. Ambitious efforts may push the technique toward sub-Neptune and terrestrial regimes, where mapping could someday reveal surface variability, cloud patterns or even indirect biosignatures under the right conditions.

For now, WASP-18b stands as a dramatic preview: a world with a searing dayside that literally rips water apart and a cooler periphery where molecules can still persist. That contrast, mapped in three dimensions, gives scientists a new, more complete way to read the weather and chemistry of planets beyond our solar system — and to ask bolder questions about how atmospheres behave under extremes we cannot replicate on Earth.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

datapulse

not convinced yet, sounds like model heavy inference. if that mapping relies on assumptions, could they be misreading dissociation vs clouds? hmm

astroset

whoa, water literally ripped apart on one side? crazy. JWST is insane but also, how clean are those maps, any chance of artifacts? gotta read the paper lol

Leave a Comment