6 Minutes

When a planet is torn apart and absorbed by its dying star, its ingredients don’t disappear — they become forensic evidence. Astronomers observing a nearby white dwarf have read those chemical fingerprints and uncovered the makeup of an ancient, Earth-like world long gone.

A startling find at Mauna Kea: a white dwarf eating a planet

Using the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, researchers have detected the spectral signatures of 13 heavy elements in the atmosphere of a white dwarf known as LSPM J0207+3331. Located roughly 145 light-years away in the constellation Triangulum, this dead Sun-like star appears to be accreting material from a shattered planetary body — and the evidence suggests the disruption happened more than 3 billion years after the star became a white dwarf.

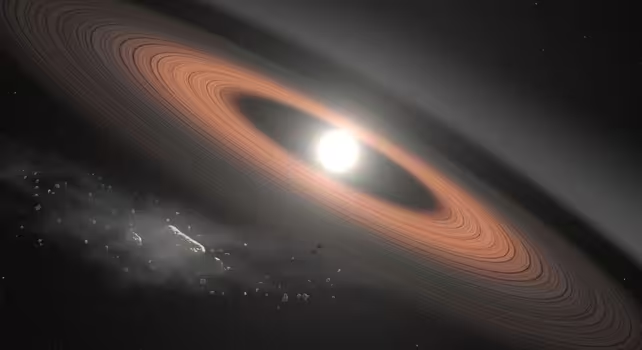

Artist's impression of the white dwarf LSPM J0207+3331 gravitationally destroying an asteroid. It is the oldest, coldest white dwarf known to be surrounded by a debris disk

Discovering active accretion around such an old, cool white dwarf is unexpected. As Érika Le Bourdais of the University of Montreal, lead author on the study, points out, late-stage destruction “challenges our understanding of planetary system evolution.” More importantly, it gives astronomers a rare window into the internal composition of an exoplanet that otherwise would be invisible to direct imaging or transit spectroscopy.

Chemical fingerprints: what the star’s atmosphere revealed

White dwarfs normally have simple, clean atmospheres. But when a broken planet spirals inward and vaporizes, heavy elements like magnesium, iron, silicon and nickel pollute the star’s outer layers. In LSPM J0207+3331, scientists identified 13 distinct heavy elements embedded in a hydrogen-rich photosphere — the largest elemental tally yet reported for a hydrogen-dominated white dwarf.

That matters because hydrogen-rich white dwarfs are common and, for cooler examples, their atmospheres are opaque. Heavy elements sink rapidly into the star’s interior — sometimes on timescales of days — making detection difficult. In contrast, helium-rich white dwarfs keep pollutants visible for millions of years. Finding so many elements in a cool, hydrogen-dominated dwarf implies a substantial and recent delivery of planetary material.

From the measured abundances, researchers infer the destroyed object had a high core mass fraction of roughly 55 percent. In other words, more than half of the planet’s mass was in a metallic core. For context, Mercury’s core fraction is around 70 percent and Earth’s is roughly 32 percent. The parent body was at least ~200 kilometers (120 miles) across and had a differentiated structure — a rocky mantle surrounding a dense metal core — similar to terrestrial planets in our own Solar System.

How does a planet get shredded so long after the star died?

One of the biggest puzzles is timing. Why would a planet be driven into a white dwarf billions of years after stellar death? There are a few leading possibilities: losing mass as a star evolves can destabilize orbital resonances, surviving massive planets can slowly perturb smaller bodies onto star-crossing orbits, or long-term chaotic dynamics within a multi-planet system eventually deliver a planetary fragment inward.

“Something clearly disturbed this system long after the star’s death,” notes co-author John Debes of the Space Telescope Science Institute. The precise mechanism remains unclear. Detecting distant, cold giant planets that might trigger such late instability is difficult, but archival astrometry from ESA’s Gaia mission combined with infrared observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope could expose the hidden culprits.

Implications for the Solar System and exoplanet science

There’s a sobering take-away: our own Sun will become a white dwarf in roughly 5 billion years. The eventual fate of Earth and the other planets will depend on complex orbital evolution; studies like this show that planetary systems can remain dynamically alive for billions of years after their stars die. More broadly, every polluted white dwarf offers a natural laboratory to sample planetary interiors across the galaxy.

By cataloguing element-by-element compositions of disrupted bodies, astronomers can test models of planet formation, differentiation, and migration on a galactic scale. Which planets preserve volatiles? Which grow large metallic cores? How common are Earth-like rocky interiors? Each white dwarf with a debris signature helps answer those questions.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Chen, an astrophysicist specializing in stellar remnants, comments: “White dwarf pollution is like cosmic archaeology. When a planet is destroyed, it writes its chemical story into the star’s atmosphere. Finding so many elements in a cool, hydrogen-rich dwarf is rare and exciting — it tells us the parent body was differentiated and massive enough to retain a substantial metal core.”

She adds, “Combining spectroscopy from ground-based telescopes with Gaia astrometry and JWST infrared imaging gives us the best chance to reconstruct the system’s dynamical history and identify any surviving giant planets that might have caused the instability.”

Where researchers go next

Follow-up work will seek archival Gaia data for subtle astrometric wobbles and target the system with deeper infrared searches. If distant, cold giants are found, they would strengthen the case for long-term, planet-driven instabilities. Meanwhile, expanding the sample of polluted white dwarfs — especially hydrogen-rich examples — will refine our picture of how common Earth-like cores are across the Milky Way.

Ultimately, the graveyard of dead stars could become the richest catalogue for studying how rocky worlds form, differentiate and decay — and, in the process, teach us about our own planet’s distant future.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

Is this even true? 13 elements in a cool hydrogen-rich white dwarf sounds too neat, maybe contamination or modeling bias. if it's right, wild.

astroset

wow didn't expect planets to turn into evidence like a crime scene, kinda poetic and terrifying. our Sun doing that someday... yikes

Leave a Comment