5 Minutes

An unexpected discovery beneath the Pacific Ocean is rewriting ideas about where life can survive. Researchers examining mud volcanoes near the Mariana Trench pulled up startlingly blue serpentinite mud from nearly 3,000 meters depth and found intact molecular signs of living cells — in a mixture so alkaline it would burn human skin.

Why this blue mud caught scientists' attention

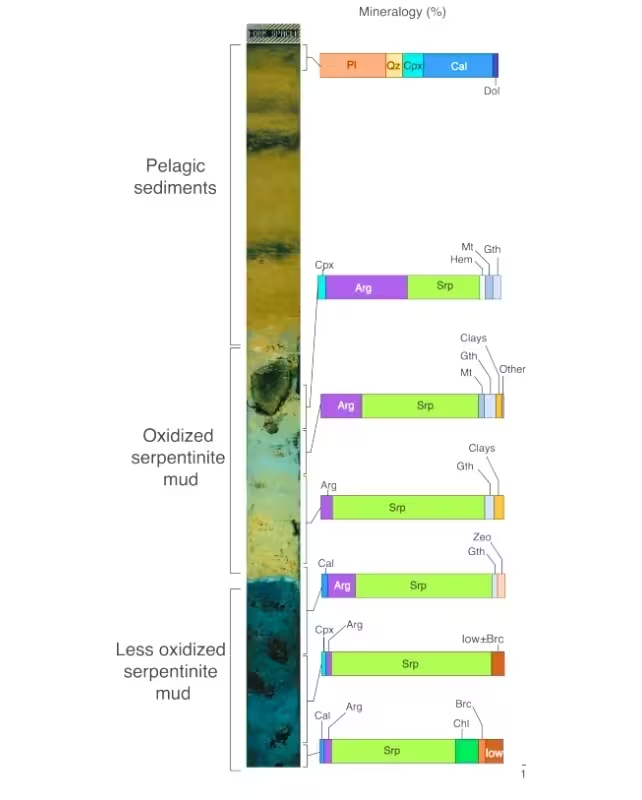

The samples were recovered during the R/V Sonne expedition SO292/2 in 2022. Palash Kumawat and colleagues analyzed two of nine cores and found one core's deepest section dominated by serpentinite rock with visible brucite crystals — minerals that give the material its electric blue color when protected from seawater. At shallower levels, where seawater had percolated in, the blue paled as brucite dissolved and the chemistry shifted.

Most striking was the chemistry: the mud registered an extremely high pH of around 12, among the most alkaline natural environments known. It is a nutrient-poor, low-organic habitat where you'd least expect life to flourish. Yet the team detected bacterial and archaeal lipids — fats that form cell membranes — preserved in remarkably intact form inside the serpentinite layers.

How microbes survive in a caustic world

Serpentinite systems arise from slow geochemical reactions called serpentinization, which generate hydrogen gas and raise pH. Those conditions favor chemosynthetic ecosystems — communities that make energy from chemical reactions instead of sunlight. In this case, the detected lipids suggest communities that metabolize methane and reduce sulfate, producing hydrogen sulfide as a byproduct.

'It is simply exciting to obtain insights into such a microbial habitat because we suspect that primordial life could have originated at precisely such sites,' says University of Bremen organic geochemist Florence Schubotz, who co-authored the research. She and colleagues emphasize that intact membrane fats indicate living or recently active populations adapted to extremes of high alkalinity and very low organic carbon.

Previous studies inferred the presence of methane-consuming and methane-producing microbes in similar systems, but this work provides direct molecular evidence from deep, dense serpentinite mud — extending the known depth and density range for such life.

Anatomy of the core sample retrieved from the Pacman mud volcano, showing serpentinite (Srp) and brucite (Brc) at lower depths. (Kumawat et al., Commun. Earth Environ., 2025)

What this tells us about Earth's deep biosphere

Life beneath the seafloor may account for roughly 15% of Earth's biomass, playing a major role in long-term nutrient and carbon cycles. Yet most of that biosphere remains unexplored. Finding biosignatures preserved within alkaline serpentinite mud shows that complex microbial ecosystems can persist in pockets shielded from seawater and sustained by geochemical energy.

The evidence also highlights abrupt ecological shifts: the team saw a clear change in organism types between the pelagic sediment that overlays the ocean floor and the deep serpentinite mud below. That boundary looks like a sharp transition from seawater-influenced communities to ancient, rock-hosted ecosystems.

Expedition, methods and implications for origins research

The research combines careful coring from seafloor mud volcanoes, mineralogical analysis to identify serpentinite and brucite, and organic geochemistry to isolate membrane lipids. Such biomarkers are robust indicators of bacteria and archaea; their preservation in high-pH, low-carbon settings is notable because alkaline water tends to break down organic molecules.

Scientists are excited because serpentinite-hosted habitats are prime candidates for scenarios about the origin of life. If simple microbes can thrive in these high-pH, methane-rich niches today, similar environments on the early Earth — or subsurface worlds on other planets and icy moons — could have supported the chemical pathways that gave rise to life.

Future steps and ongoing research

Kumawat and collaborators plan to broaden sampling across more mud volcanoes, combine lipid data with DNA and single-cell studies, and run lab experiments simulating the high-pH, low-organic conditions found in the cores. Understanding how membrane chemistry and metabolic pathways adapt to extreme alkalinity will be key.

Expert Insight

Dr. Leah Moreno, an astrobiologist at the Institute for Planetary Science, comments: 'These findings strengthen the idea that life is tenacious and opportunistic. Serpentinizing systems are natural laboratories for studying prebiotic chemistry and microbial survival strategies. For astrobiology, they are particularly compelling analogs for subsurface habitats on Mars or ocean worlds like Europa.'

By extending exploration into these dense, blue muds, scientists hope to map previously hidden ecosystems and better constrain the environmental windows where life can start and persist.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

is this even real? intact membrane lipids in super-alkaline mud sounds like contamination risk. did they rule out modern seepage or lab artefacts?

labcore

wow blue serpentinite at 3,000m? microbes surviving in pH ~12... mind blown. if primordial life liked this, that shifts hypotheses big time, ok

Leave a Comment