6 Minutes

The Moon is a calm, airless world to the naked eye — no weather, no wind, no storms — but it sits beneath a relentless drizzle of micrometeoroids. As NASA's Artemis program plans long-duration stays and a permanent base, researchers are quantifying how this invisible rain could shape design choices, site selection, and astronaut safety.

Why the Moon is under constant fire

Micrometeoroids are tiny fragments of rock and metal — often much smaller than a grain of sand — that travel at extremely high speeds, sometimes up to 70 kilometers per second. On Earth, the atmosphere burns most of them away. On the Moon, with no air to slow or vaporize incoming debris, every particle that intersects the surface arrives at full hypervelocity and can deliver significant destructive energy.

Using NASA's Meteoroid Engineering Model (MEM), a team led by Daniel Yahalomi calculated impact rates for a notional lunar outpost about the size of the International Space Station. Their results are stark: a habitat that size could endure roughly 15,000 to 23,000 micrometeoroid impacts per year. The particles responsible range from a millionth of a gram to ten grams. Even a one-microgram grain — invisible without magnification — can crater metal and has the potential to puncture thin equipment, degrading seals or thermal layers over time.

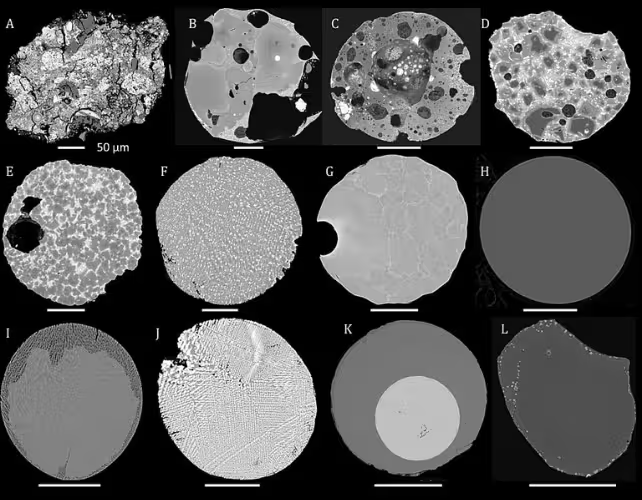

Cross sections of different micrometeorite classes: a) Fine-grained unmelted; b) Coarse-grained Unmelted; c) Scoriaceous; d) Relict-grain Bearing; e) Porphyritic; f) Barred olivine; g) Cryptocrystalline; h) Glass; i) CAT; j) G-type; k) I-type; and l) Single mineral. Except for G- and I-types, all are silicate-rich, called stony MMs. Scale bars are 50 μm. (Shaw Street)

Impact frequency and energy are not uniform across the lunar surface. Yahalomi's modeling shows geographic differences tied to the Moon's orbital geometry and its interaction with meteoroid streams. The lunar poles experience the lowest bombardment rates — a favorable factor for the south pole, which NASA has targeted for Artemis Base Camp. By contrast, regions near the sub-Earth longitude (the hemisphere permanently oriented toward Earth) face the highest flux. Overall, impact rates vary by about a factor of 1.6 between the calmest and most exposed zones.

Shielding strategies and mission implications

Protection will be central to long-term lunar operations. The team evaluated aluminum Whipple shields — multilayer bumper systems similar to those used on the International Space Station — to see how they perform in the lunar environment. A Whipple shield uses an outer sacrificial sheet to shatter and vaporize an incoming particle, spreading the resulting energy across a broader area before it reaches the primary habitat wall.

The researchers derived mathematical relationships that link shield configuration, local impact flux, and penetration probability. These formulas let engineers calculate the precise thickness and layering needed to reduce puncture risk to acceptable levels without carrying excessive mass from Earth — a key trade-off because every kilogram launched increases mission cost and complexity.

But shielding is only part of the solution. Operational strategies such as orienting habitats to minimize exposure, burying modules under regolith, using berms or prefabricated subsurface cavities, and regular inspection and maintenance of vulnerable systems will all factor into resilient designs. For spacesuits and EVA operations, redundancy and quick-repair kits could mean the difference between a minor breach and a mission-ending emergency.

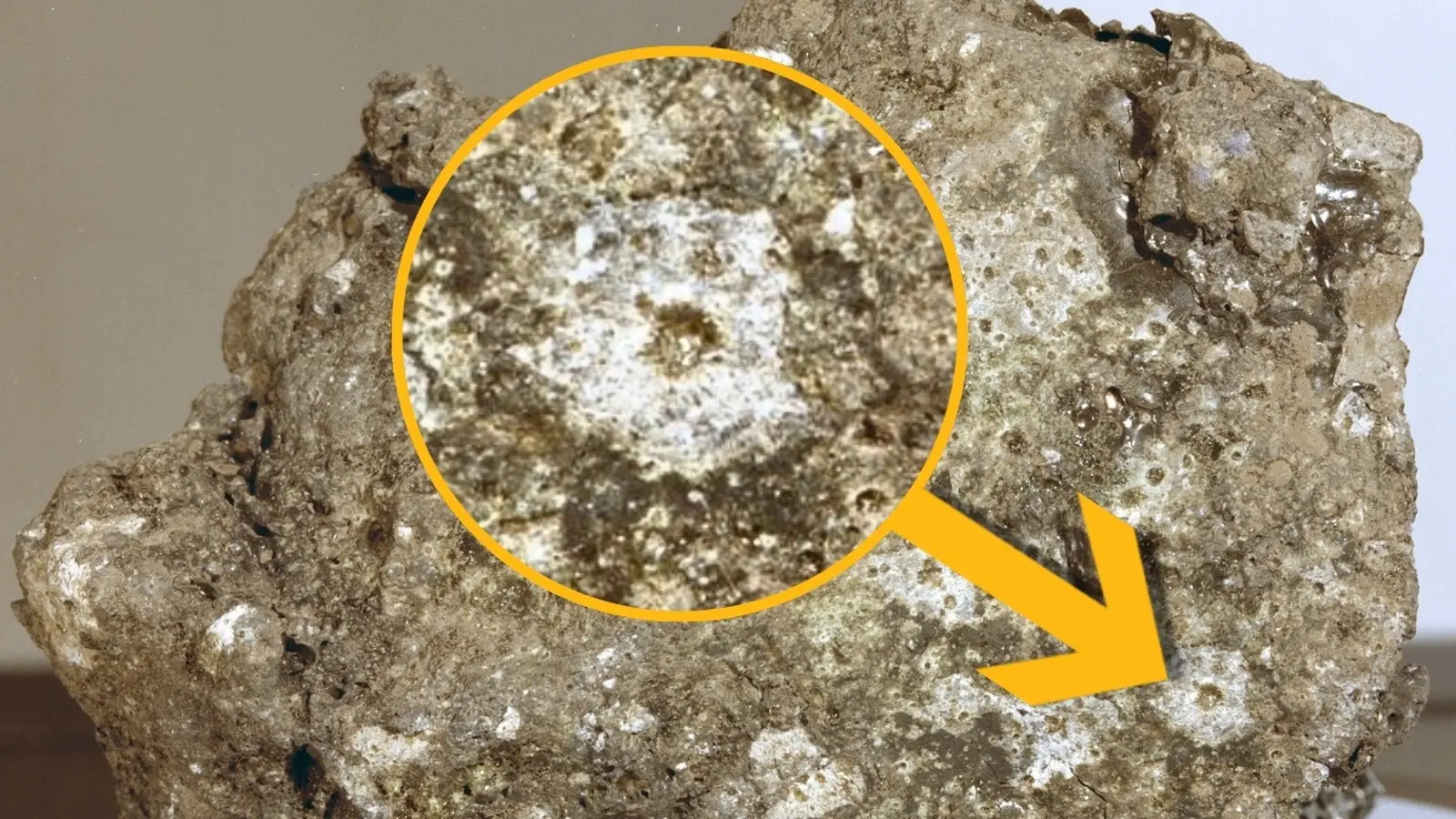

Artist impression of the Artemis Base Camp. (NASA)

Long-term risks and daily life on the Moon

For crews living on the Moon for months at a time, micrometeoroid impacts will be an everyday background hazard: tiny pings on the hull, gradual erosion of exposed surfaces, and a cumulative risk to power, thermal control, and life-support penetrations. Designers must weigh micrometeoroid protection alongside priorities such as access to water-ice, reliable communications with Earth, and solar illumination.

Understanding regional bombardment patterns also helps mission planners pick sites that balance natural protection with science and logistics. The poles offer lower flux and ice resources; equatorial or sub-Earth locations may simplify communications but require beefier shielding.

Expert Insight

"What surprises many engineers is how pervasive the risk is," says Dr. Elena Morales, a lunar systems engineer (fictional) who has worked on habitat protection concepts. "Micrometeoroid impacts are not dramatic explosions — they are relentless and cumulative. You design for thousands of micro-hits over the lifetime of the habitat, not just the occasional big rock. That changes how we think about redundancy, maintenance, and material selection."

As Artemis moves from visits to sustained presence, micrometeoroid modeling, smart shielding, and operational discipline will become foundational components of lunar architecture. The Moon may lack an atmosphere, but it does not lack challenges — and the tiny particles it throws at us are a reminder that even nearby space is a hostile environment that must be respected and engineered for.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

coinpilot

Is that 15k hits per year for an ISS-sized habitat real? sounds crazy, can shields be light enough without huge launch costs, if true then...

astroset

wow ok tiny rocks punching holes nonstop? kinda spooky. designing habitats to take thousands of micro hits, that's a whole new ballgame. yikes

Leave a Comment