4 Minutes

New research suggests that when it comes to following a conversation in a crowded room, what matters may not be your ears alone but also how your brain handles sound. A recent study led by the University of Washington links lower cognitive ability with greater difficulty understanding speech amid background noise — even if standard hearing tests come back normal.

Untangling voices: the cocktail party problem and cognition

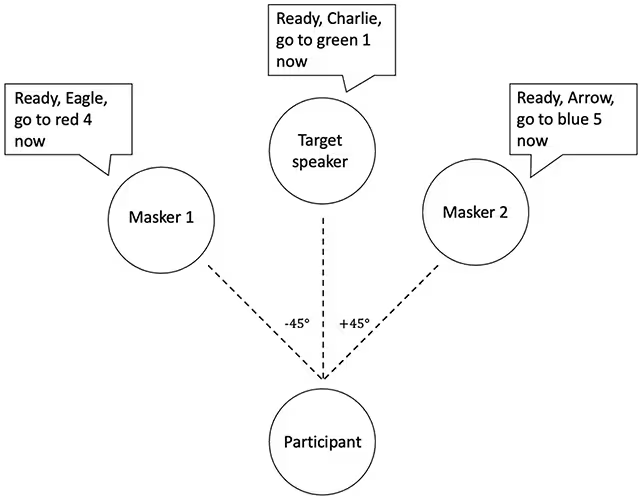

Researchers tested volunteers on a classic listening challenge often called the 'cocktail party problem' — the ability to focus on a single voice while multiple others are talking. Rather than relying on real conversations, the team used computer-generated speech streams so they could precisely control how voices overlapped. Participants were asked to follow instructions embedded in target conversations while other voices played simultaneously.

The study group included 12 people with autism and 10 with fetal alcohol syndrome, conditions previously linked to trouble hearing in noisy settings and spanning a range of IQ levels. A control group of 27 neurotypical participants, matched for age and sex, completed the same tasks. Importantly, all participants had clinically normal peripheral hearing, meaning their ears detected sounds within expected ranges on standard tests.

What the results reveal about speech perception and IQ

Across the three groups, lower cognitive ability corresponded with worse performance on the speech-in-noise task. As auditory neuroscientist Bonnie Lau at the University of Washington put it, 'The relationship between cognitive ability and speech-perception performance transcended diagnostic categories.' In short: IQ-related differences in processing — rather than measurable hearing loss — appear to drive difficulty picking out speech from background chatter.

That makes intuitive sense. Isolating a single voice requires rapid segregation of audio streams, selective attention, working memory to hold parts of the sentence, and sometimes visual cues such as lip reading. All of these processes increase cognitive load, especially in complex acoustic scenes. 'All these factors increase the cognitive load of communicating when it is noisy,' the researchers note.

Practical implications: more than a hearing test

The study's authors emphasize that standard audiograms can miss these central, cognitive sources of listening difficulty. Someone can 'pass' a hearing test yet still struggle to follow a conversation in a busy café or classroom. Recognizing this opens up low-cost, practical interventions: moving a student closer to the teacher, improving classroom acoustics, or using targeted auditory training to strengthen attention and stream segregation skills.

The researchers acknowledge limitations, including a relatively small sample size and the use of synthesized speech rather than natural conversations. Still, the findings add weight to a growing body of work showing that speech-in-noise problems are multifactorial and sometimes linked to broader cognitive decline; earlier research has even connected similar listening difficulties to increased dementia risk.

Why scientists are paying attention

Understanding the neural and cognitive underpinnings of speech perception has wide-ranging relevance. For clinicians, it reframes diagnostic approaches to listening complaints. For educators, it suggests seating and acoustic strategies that could dramatically improve comprehension for some students. For technologists developing hearing-assistive devices and algorithms, the results underline the need to incorporate models of attention and scene analysis, not just amplification.

As the authors conclude, you do not need to have measurable hearing loss to find everyday noisy places exhausting and confusing. The next steps include larger studies, more diverse participant samples, and interventions that target the brain systems involved in separating, prioritizing, and remembering speech.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment