5 Minutes

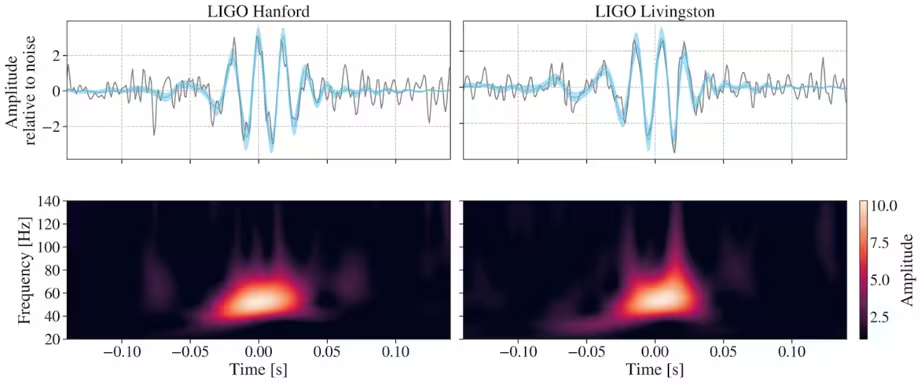

In 2023, gravitational wave observatories recorded a collision so strange it seemed to break the rules physicists rely on. The signal, labeled GW231123, came from a merger seven billion light-years away yet carried the fingerprints of black holes that—by standard stellar theory—should not exist.

A merger that challenged astrophysics

When astronomers unpacked the GW231123 waveform they found two unexpected properties: the component black holes sat inside the so-called pair-instability mass gap, and they were spinning at speeds approaching the speed of light. That combination was puzzling. Stars that start with roughly 70 to 140 times the Sun’s mass are predicted to experience pair-instability supernovae, a runaway process that completely obliterates the star and leaves no compact remnant behind.

Standard explanations invoked exotic formation channels: repeated mergers in dense star clusters or hierarchical growth where earlier black hole collisions seed heavier second-generation black holes. But those pathways tend to randomize spin—making the discovery of two massive, fast-spinning black holes colliding in a single event highly unlikely.

.avif)

What simulations missed: magnetic fields

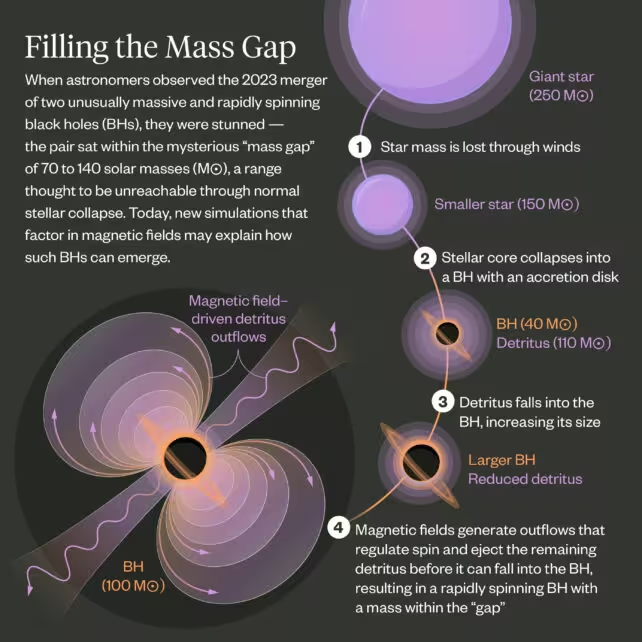

A team led by researchers at the Flatiron Institute's Center for Computational Astrophysics revisited the problem with a crucial ingredient: magnetism. Previous computational models had focused on gravity and nuclear physics but commonly simplified or omitted magnetic fields. The Flatiron simulations traced a very massive star—initially about 250 times the mass of the Sun—through its lifecycle and collapse, while explicitly modeling magnetic fields in the dying star's leftover disk.

The result flips part of the standard story. After late-stage nuclear burning, the simulated star had shed much of its outer layers and weighed in at roughly 150 solar masses—right at the edge of the forbidden mass gap. When the core collapsed, it formed a newborn black hole surrounded by a dense, rapidly rotating accretion disk threaded with magnetic fields.

Magnetic pressure: a hidden moderator

Strong magnetic fields act like an extra source of pressure inside the disk. Instead of allowing all remaining mass to spiral into the hole, magnetically driven winds can eject a substantial fraction of the disk—up to half the mass—at relativistic speeds. That ejection reduces the final black hole mass, shifting objects that would otherwise sit inside the pair-instability gap down into allowed mass ranges. Magnetic torques also remove angular momentum from the forming black hole, lowering its spin.

Crucially, the simulations show a systematic link: stronger fields produce lighter, slower-spinning black holes, while weaker fields permit heavier, faster-spinning remnants. This creates a mass–spin relationship that could explain the unusual parameters extracted from GW231123 without invoking improbable formation histories.

Observational tests and wider implications

One attractive feature of the magnetic-wind scenario is that it makes testable predictions. The same magnetically powered outflows that strip mass from the collapsing star should produce high-energy transients—brief gamma-ray bursts or other electromagnetic counterparts—when they break out of the stellar envelope. If future gravitational-wave detections of in-gap, high-spin mergers come with corresponding short gamma-ray signals, that would strongly support the magnetic interpretation.

More broadly, this work suggests astrophysicists should treat stellar magnetism as a first-order effect in models of black hole birth. It also supplies a new diagnostic: measuring both mass and spin across many black hole mergers could reveal the imprint of magnetic processes and help map the distribution of massive star magnetic fields in the early universe.

Expert Insight

“These simulations show how messy, real stellar deaths can be,” says Dr. Mira Patel, an astrophysicist who studies compact-object formation. “Magnetic fields are not a small correction here—they can fundamentally change whether a star leaves behind a black hole and how fast that black hole spins. Observationally, this gives us clear signatures to chase: in-gap masses tied to specific spin ranges and potentially coincident gamma-ray flashes.”

As gravitational-wave catalogs grow and multimessenger follow-ups become faster and more sensitive, researchers will be able to test whether magnetic shaping of stellar collapse is the rule or an exception. If confirmed, the magnetic-wind mechanism would resolve one of the sharpest puzzles raised by GW231123 and alter how we think about the final act of the most massive stars.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyforge

Sounds neat but is magnetism really that dominant? Simulations can be tuned, maybe selection bias? Need multiple detections and em counterparts...

labmesh

Whoa, magnetic winds rewriting black hole birth? Mind blown. If gamma flashes show up, that's huge… gotta see more data, pronto.

Leave a Comment