6 Minutes

Astronomers have identified a potentially habitable world close to the Solar System: a rocky "super-Earth" orbiting an M-dwarf just 18 light-years away. Early measurements suggest the planet, called GJ 251 c, could lie in its star's habitable zone where temperatures may permit liquid water on its surface — a key ingredient for life as we know it.

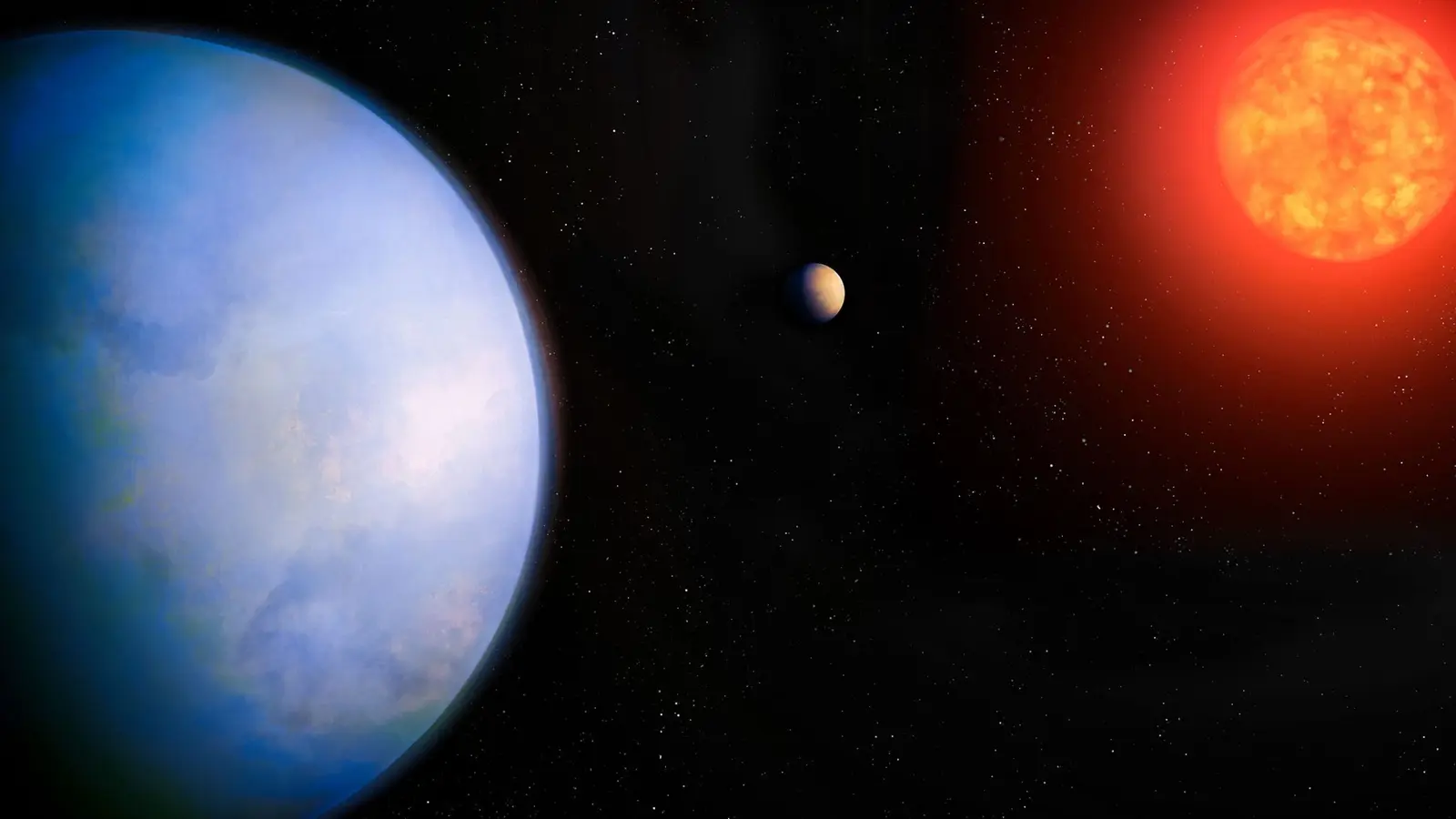

An international team of scientists dubbed the exoplanet, named GJ 251 c, a “super-Earth” as data suggest it has a rocky composition similar to Earth and is almost four times as massive. Credit: Illustration by University of California Irvine

A nearby world with big implications

GJ 251 c stands out for two reasons: its proximity and its composition. Located roughly 18 light-years from Earth, the planet orbits an M-dwarf — the most abundant stellar type in the Milky Way. Observations indicate a rocky bulk with a mass several times that of Earth, placing it in the "super-Earth" category. Because it lies within the star's habitable zone, researchers say conditions could allow surface temperatures compatible with liquid water.

"We have found so many exoplanets at this point that discovering a new one is not such a big deal," said Paul Robertson, associate professor of physics & astronomy at UC Irvine and a co-author on the study. "What makes this especially valuable is that its host star is close by, at just about 18 light-years away. Cosmically speaking, it’s practically next door."

How the planet was found: instruments and technique

GJ 251 c was detected using precision radial velocity (RV) measurements from two cutting-edge instruments: the Habitable-zone Planet Finder (HPF) and NEID. These spectrographs measure minute shifts in starlight caused by the gravitational tug of an orbiting planet. As the planet orbits, its gravity makes the star wobble, producing tiny Doppler shifts in the star's spectrum that trained instruments can detect.

Detecting planets around M-dwarfs is especially challenging because these stars are often magnetically active. Starspots and flares can introduce signals that mimic or obscure the faint RV signatures of small planets. The HPF instrument mitigates some of that noise by operating in the infrared, a wavelength range where stellar activity is less pronounced for many M-dwarfs. NEID, operating at optical wavelengths on a different telescope, provided complementary data that helped confirm the periodic signal consistent with an orbiting body.

Why proximity matters: direct imaging prospects

Because GJ 251 c is relatively close to Earth, it becomes a prime candidate for future direct imaging studies. Direct imaging means resolving the faint light of a planet from the glare of its host star — a capability expected from the next generation of extremely large telescopes. The University of California’s Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), with its enormous primary mirror and advanced adaptive optics, may be able to directly image exoplanets like GJ 251 c and test for atmospheric features or surface water.

"TMT will be the only telescope with sufficient resolution to image exoplanets like this one. It’s just not possible with smaller telescopes," said Corey Beard, Ph.D., data scientist at Design West Technologies and the study’s lead author, emphasizing how larger apertures open a new window for characterization.

On Oct. 4, at the closing ceremony for UC Irvine’s Brilliant Future fundraising campaign, Paul Robertson, associate professor of physics and astronomy, shared with the audience some exciting information about a study by he and his colleagues of an exoplanet orbiting a neighboring star. Credit: Steve Zylius / UC Irvine

Scientific context and what remains uncertain

The detection team reports that the statistical evidence for GJ 251 c is strong, but they caution that instrumental limits and stellar activity still leave room for uncertainty. Radial velocity provides a minimum mass and orbital period, not a direct measurement of radius or atmosphere. To confirm whether liquid water exists, astronomers will need direct imaging or transit detections that allow atmospheric spectroscopy.

Even without immediate confirmation, the discovery is an important step. Nearby M-dwarf systems are accessible to multiple techniques — radial velocity, transit photometry, and eventually direct imaging — giving scientists a suite of tools to probe planetary composition, climate, and habitability. The HPF and NEID instruments used for this discovery were built specifically to push these measurement boundaries, demonstrating how targeted instrumentation drives new science.

Looking ahead: community investment and next steps

The researchers emphasize community support for next-generation observatories and follow-up campaigns. Confirming GJ 251 c as a truly habitable world requires sustained observation time on large telescopes and allocation of resources for data analysis and modeling. The team hopes their result will motivate further study of this system ahead of TMT and similar facilities coming online.

Expert Insight

"A nearby super-Earth in the habitable zone is exactly the kind of target we want to prioritize," said Dr. Lena Ortiz, an astrophysicist who studies exoplanet atmospheres. "If we can combine radial velocity, transit data, and direct imaging, we stand a real chance of measuring atmospheric gases and surface conditions. That’s the roadmap to answering whether nearby rocky planets can support life."

GJ 251 c will now join a shortlist of accessible, potentially temperate exoplanets that are within reach of the next wave of instruments. For researchers and the public alike, a world this close sparks both scientific opportunity and renewed curiosity about life beyond Earth.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

skyspin

wait, how sure are they? m-dwarfs mess with RVs, starspots, flares... minimum mass only, no radius or atm info. looks promising but premature, no?

astroset

Whoa, a super-Earth only 18 ly away? This actually gives me chills. If TMT can image it, that'd be wild... fingers crossed but hopeful!

Leave a Comment