5 Minutes

A tiny, stress-sensitive population of neurons deep in the cortex may be orchestrating blood flow and electrical activity across the whole brain. New experiments in mice suggest these rare cells — known as type-I nNOS neurons — play an outsized role in sleep-related brain rhythms, waste clearance, and possibly the early stages of neurodegenerative disease.

How a few cells influence the whole brain

Type-I nNOS neurons are sparse and hidden mostly in deep cortical layers, but they appear to punch above their weight. Researchers at Pennsylvania State University used targeted methods to remove this cell type in mice and then monitored what happened to cerebral blood flow, the slow pulsations of vessels called vasomotion, and overall neural activity.

The results were striking. Animals lacking type-I nNOS neurons showed lower global blood flow, weaker vasomotion, and reduced neural firing. Slow delta waves — the brain rhythms linked to deep sleep and memory consolidation — diminished in amplitude, and the normal synchronization between left and right hemispheres faltered.

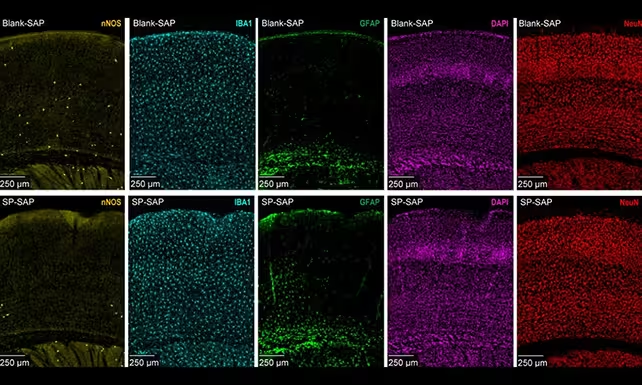

Type-I nNOS neurons (in yellow) are much less abundant than other types, and were selectively removed by the researchers.

Why vasomotion and slow waves matter

Vasomotion refers to the spontaneous, rhythmic dilation and constriction of cerebral arteries, veins, and capillaries every few seconds. This ongoing oscillation helps move interstitial fluid and cerebrospinal fluid through brain tissue, a process that supports the removal of metabolic waste. When vasomotion weakens, clearance of toxic proteins — like those implicated in Alzheimer's disease — can be impaired.

The Penn State team found that the decrease in blood flow and neural activity was most pronounced during sleep, when delta waves normally dominate. That connection raises an important possibility: if type-I nNOS neurons are compromised, sleep architecture and the brain’s nightly cleansing operations could both suffer. Over time, those changes might contribute to cognitive decline.

Experimental details and implications

Using cell-specific ablation in mice, investigators were able to isolate the role of type-I nNOS neurons without broadly damaging surrounding tissue. The intervention reduced the amplitude of spontaneous vascular oscillations and blunted the brain’s slow-wave activity. These linked changes in vascular and neural dynamics suggest the affected neurons act as a hub, coordinating blood supply with network activity.

Biomedical engineer Patrick Drew, whose lab has previously mapped nNOS-related blood-flow regulation, describes spontaneous oscillation as the brain’s way of moving fluid by rhythmically dilating and constricting vessels every few seconds. Loss of the neurons that help time and tune those oscillations, he and colleagues argue, could create a cascade of dysfunction affecting sleep, waste clearance, and long-term brain health.

From mice to humans: what’s plausible?

These findings come from mouse models, and translating them to human brains will require more work. Still, many fundamental vascular and neural processes are conserved across mammals, so the idea that a small, stress-vulnerable neuronal population could influence whole-brain dynamics is credible. If similar cells exist and behave likewise in humans, their loss through chronic stress, aging, or disease could be a previously underappreciated driver of neurodegeneration.

Reduced cerebral blood flow is already recognized as a contributor to impaired cognition and dementia. The new data add nuance by identifying a specific cell type that links vascular tone, slow-wave sleep, and interhemispheric synchrony — all factors relevant to healthy cognition.

What researchers will study next

Future experiments will need to confirm whether human brains rely on an equivalent population of type-I nNOS neurons. Scientists will also probe how stress, inflammation, or aging selectively damage these cells and whether such loss precedes measurable cognitive symptoms. If the connection holds, protecting or restoring this neuronal cohort could become a target for therapies aimed at improving sleep quality and slowing neurodegenerative processes.

Expert Insight

Dr. Claire Mendoza, a neurovascular researcher not involved in the study, says: "The idea that a rare cell type can coordinate vascular rhythms across the brain is exciting. It reframes how we think about blood flow regulation — not just as a local response to activity, but as a networked process that supports sleep and waste clearance. Investigating resilience and vulnerability of these neurons could open new preventative strategies for dementia."

Understanding how stress affects these neurons also has public-health implications. Chronic stress is pervasive in modern life; if it selectively weakens the cells that regulate cerebral blood flow, then stress reduction and vascular-protective interventions may offer a route to preserve brain health as we age.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

skeptical here, mice studies are neat but humans? are these cells even common in our cortex or just a rodent quirk, need better evidence

bioNix

wow this blew my mind, that tiny cell group could mess up sleep and waste clearance… if true, yikes. stress link??

Leave a Comment