7 Minutes

When an experiment goes wrong in the lab, it can open a new door. That is exactly what happened to Andrea Stöllner and her team: an unexpected behavior of a single trapped particle has become a fresh, high-resolution way to probe how nature might ignite lightning. Using lasers as optical tweezers, the researchers observed microscopic charging and abrupt discharges that echo, in miniature, one of atmospheric science's oldest mysteries.

Why lightning initiation still puzzles scientists

Lightning lights up the planet nearly 9 million times a day, producing dramatic electrical discharges that have fascinated humans for millennia. Yet despite extensive field campaigns, airborne measurements, and high-speed imaging, the mechanism that launches the first step of a lightning bolt inside a thundercloud remains unresolved. The basic ingredients are known: collisions between graupel (soft hail) and ice crystals separate charges, creating strong electric fields inside storms. But measured field strengths usually fall short of the theoretical threshold needed to turn air into a conductor.

That gap between observation and theory has driven multiple hypotheses. Perhaps there are tiny pockets of intense field that elude instruments. Maybe cosmic rays momentarily ionize a column of air and seed a discharge. Or ice particles themselves might undergo microscopic charge exchanges that cascade upward. As Joseph Dwyer and Martin Uman noted in 2014, either our cloud measurements are missing something, or our understanding of discharge physics in storms is incomplete.

How lasers and a single silica particle became a laboratory lightning lab

Stöllner, a physicist at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, was not originally trying to solve lightning. Working with Scott Waitukaitis and Caroline Muller, she used an optical tweezers setup to trap a single submicron silica particle in air and monitor its electric charge. By slowly increasing laser intensity, the team found the neutral particle could become positively charged: multiphoton absorption from the trapping laser liberated electrons, leaving the grain with a net positive charge.

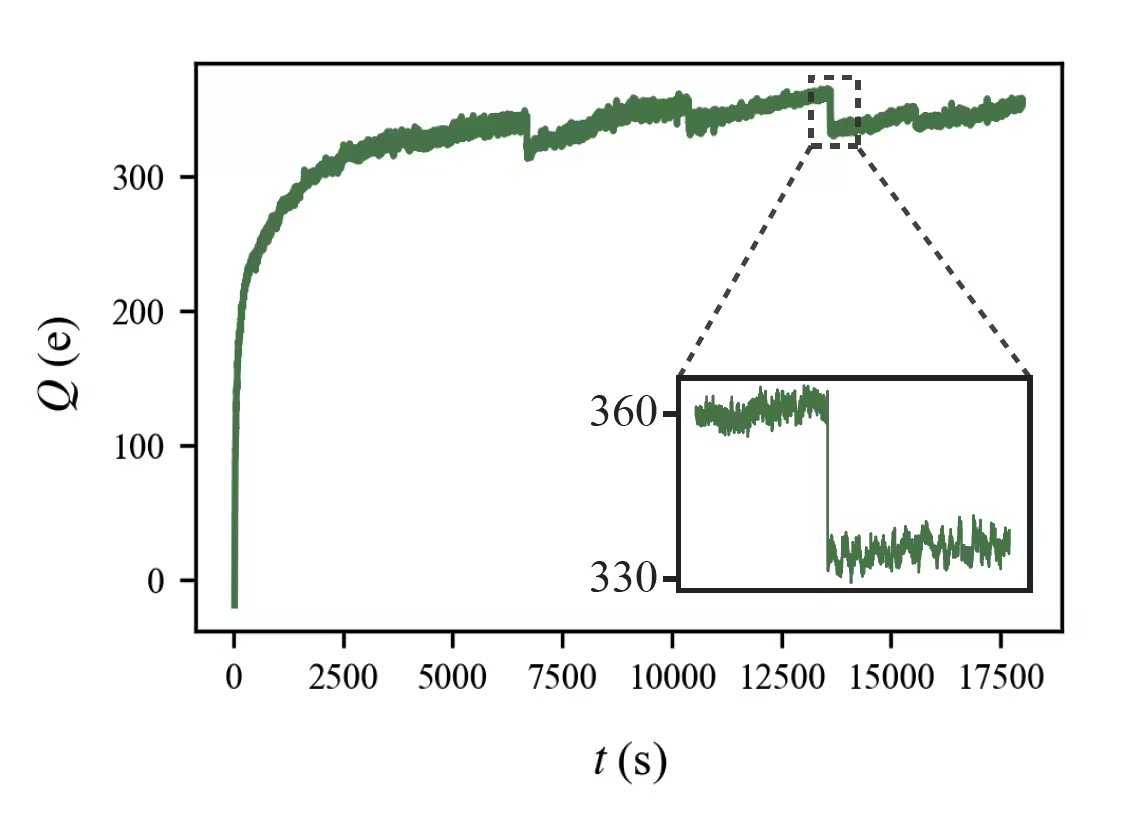

As the particle gathered charge, it started to oscillate in the alternating optical and electric fields of the trap. Those motions were measured with high sensitivity, giving the researchers an unprecedented, continuous readout of the particle's charge state. In some runs, however, the charged particle would suddenly stop oscillating as vigorously — a rapid loss of charge, or 'microdischarge'. That fast discharge event is intriguing because, on a vastly larger scale, a similar runaway could be the seed of a lightning leader.

One of the 'microdischarges' observed in the experiments. The inset shows a discharge with a magnitude of around 30e.

What the microdischarges tell us — and what they don't

The experimental system offers several strengths compared with older lab approaches. It measures charging without metal electrodes, so the particle hovers freely in air like an aerosol or dust grain in the atmosphere. The electric fields used are relatively weak, closer to the conditions inside thunderclouds than many previous setups. And the charge readout works with exquisite resolution: the team can detect changes of just a few elementary charges.

Still, there are clear limitations. Ice crystals, not silica dust, are thought to play the central role in cloud electrification, and they have complex shapes and surface chemistries that affect charge transfer. Sunlight and solar UV that reach Earth's atmosphere are far weaker than the lasers used in the lab, and while multiphoton processes can dominate under intense laser illumination, natural ionization by UV or cosmic rays may follow different pathways. Dan Daniel, a physicist at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, praised the technical precision of the method while noting the need to relate those microphysics to real cloud particles like ice and water droplets.

Implications for atmospheric electricity and planetary science

Even if 10 electrons will never create a thunderbolt, the experiments provide a microscopic window into charge accumulation and sudden discharge on airborne particles. That matters because lightning initiation likely depends on a chain of microscopic events that amplify into macroscopic currents. If single-particle discharges can be triggered by ambient conditions such as humidity, pressure, or particle size, those triggers could be modeled and sought inside storms.

Beyond Earth, the approach has planetary relevance. Lunar dust becomes charged under solar UV and plasma, leading to levitation that can impair instruments and rovers. Understanding how tiny grains gain and lose charge helps mission planning and surface operations on the Moon, Mars, and other dusty worlds. Likewise, laboratory methods that avoid electrodes and measure free-floating particles more closely mimic aerosol and dust dynamics across the Solar System.

What comes next for the research

Stöllner and colleagues are expanding their experiments to test how particle size, humidity, gas pressure, and material composition affect charging and discharge behavior. They aim to trap water droplets and ice particles to see whether similar microdischarges appear. If they do, that would strengthen the relevance of the findings to cloud electrification and lightning initiation. The team is also investigating the trigger for the spontaneous discharges: is it a change in surface states, a mechanical instability, or a sudden local breakdown of the surrounding air?

The researchers are careful to avoid overclaiming. 'We don't know how it happens, but basically the charge just drops very quickly,' Stöllner told colleagues. 'We're very interested in finding out what causes that, and that is actually pretty much the same question as lightning initiation, just on this tiny, tiny scale.'

Expert Insight

'Laboratory precision at the single-particle level is exactly what we need to bridge the gap between cloud-scale observations and microscopic physics,' says Dr. Lena Moreno, a hypothetical atmospheric physicist and science communicator. 'If even modest discharges occur in realistic ice or droplet analogs, we can start to map how microphysics cascade into macro-scale leaders. That would be a major step toward resolving a long-standing puzzle in atmospheric electricity.'

Broader technologies and future prospects

The techniques used in the study — optical trapping, sensitive charge readout, and controlled multiphoton ionization — are maturing rapidly. They could be applied to study charging of aerosols in polluted atmospheres, charging of cometary grains, or interactions of dust with spacecraft surfaces. If cross-disciplinary teams can trap ice in controlled environments while varying UV flux and cosmic-ray analogs, the gap between lab and cloud could narrow further.

For now, the link between microscopic laser-induced discharges and a thundercloud's massive electrical architecture remains speculative but promising. These experiments do not yet claim to reproduce lightning initiation, but they point to a new experimental pathway: study the tiniest sparks, and you may gradually reconstruct how the largest ones begin.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

Is multiphoton ionization really comparable to cosmic rays in clouds? feels like laser conditions are way too extreme, but the single-particle readout is neat. still skeptical

labcore

wow didn't expect a lab oops to echo lightning physics, kinda poetic and spooky. If ice and UV match this, thats huge. curious about humidity effects… quick thought

Leave a Comment