9 Minutes

New high-resolution views from ESA’s Mars Express orbiter reveal striking glacial traces in the Coloe Fossae region, evidence that Mars once experienced widespread ice advances that reached far into the planet’s mid-latitudes. These surface scars—grooves, ridges and crater fills—offer a clear record of ancient martian ice ages driven by shifts in the planet’s tilt.

Reading the Martian Landscape: Coloe Fossae’s Grooves and Ridges

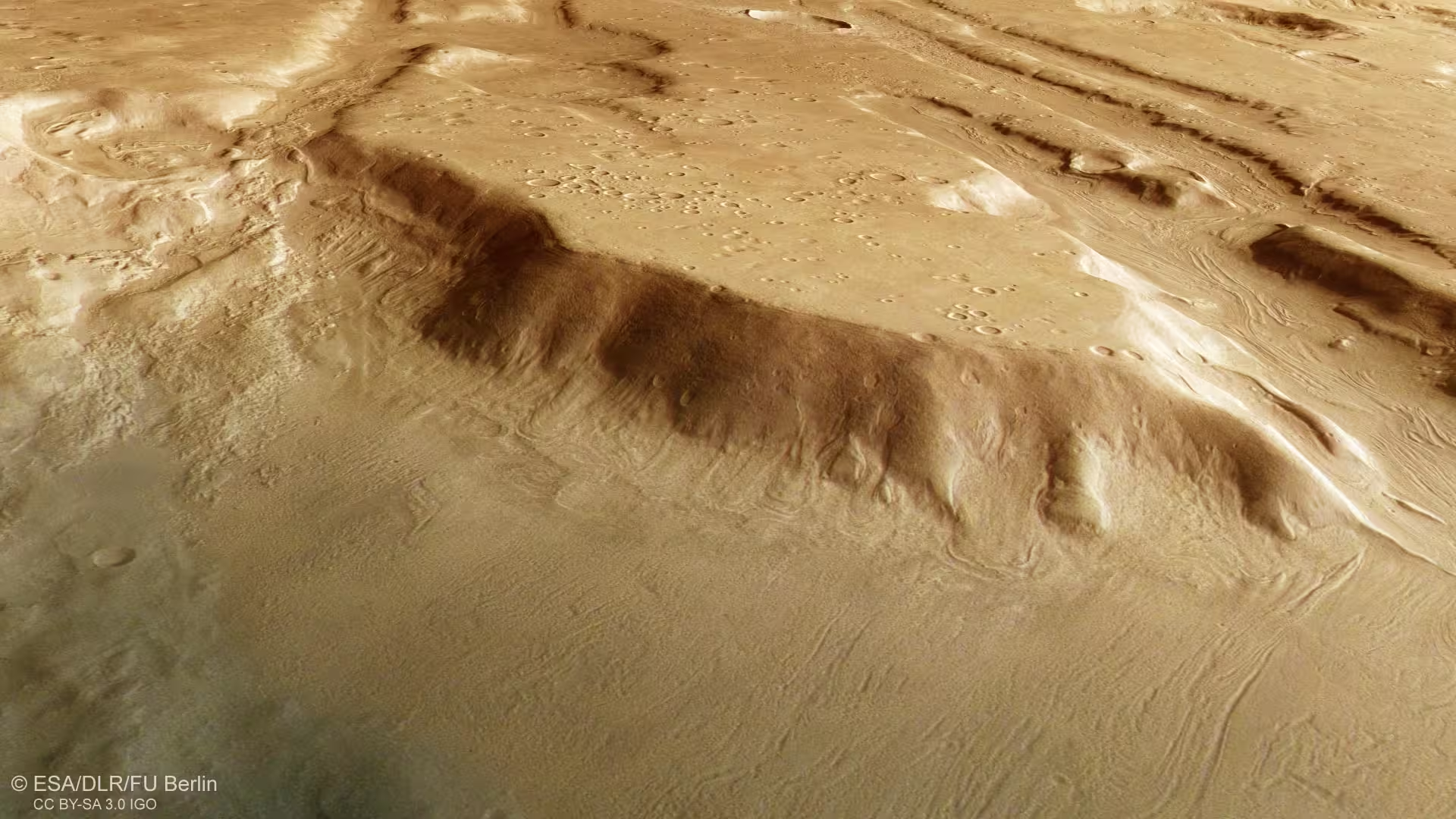

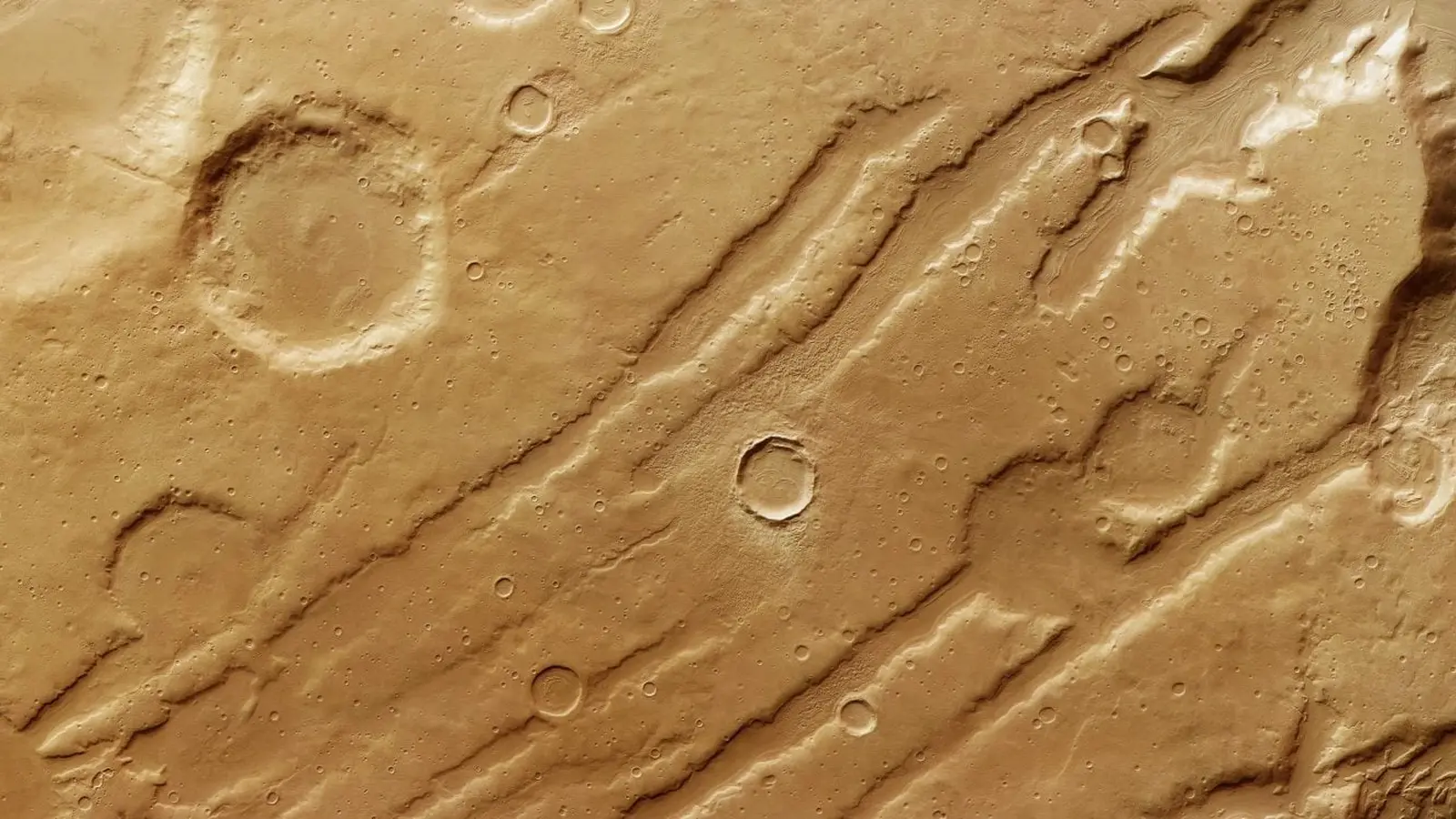

Traveling north from Mars’s equator toward its northern plains, the Coloe Fossae region stands out: long, shallow troughs cut across a terrain pocked with steep valleys and impact craters. In recent Mars Express images, those troughs are crossed by near-parallel lines and wavy textures—geological signatures that point to flowing ice in Mars’s past.

Some of the lines in the images represent faults where alternating crustal blocks dropped down, forming the characteristic fossae. But within the valleys and on crater floors, a different story appears: textures that resemble the flow and burial patterns of icy debris—patterns planetary scientists recognize from terrestrial glacial geology.

This view was generated from the digital terrain model and the nadir and colour channels of the High Resolution Stereo Camera on ESA’s Mars Express. It shows a bird’s-eye view of the Coloe Fossae region of Mars, more specifically the wavy lines that indicate where material flowed during a previous martian ice age. The lack of impact craters in the low terrain at the foot of the cliff shows that this is much younger than the (more heavily cratered) highland terrain. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

What the Patterns Mean: Lineated Valley Fill and Concentric Crater Fill

Planetary geologists use specific terms for the textures seen in the Coloe Fossae images. Lineated valley fill describes linear, flow-like deposits that occupy valleys, while concentric crater fill refers to layered, ringed deposits inside impact basins. Both form when ice mixed with rock slowly moves downslope and is later covered by debris.

On Earth, glaciers carve similar marks when they advance and retreat. On Mars, however, the driving mechanism for such large-scale redistribution of ice is different: long-term changes in orbital parameters—especially the planet’s axial tilt, or obliquity—alter the distribution of sunlight and cold traps, causing ice to move from poles toward mid-latitudes and back again over hundreds of thousands to millions of years.

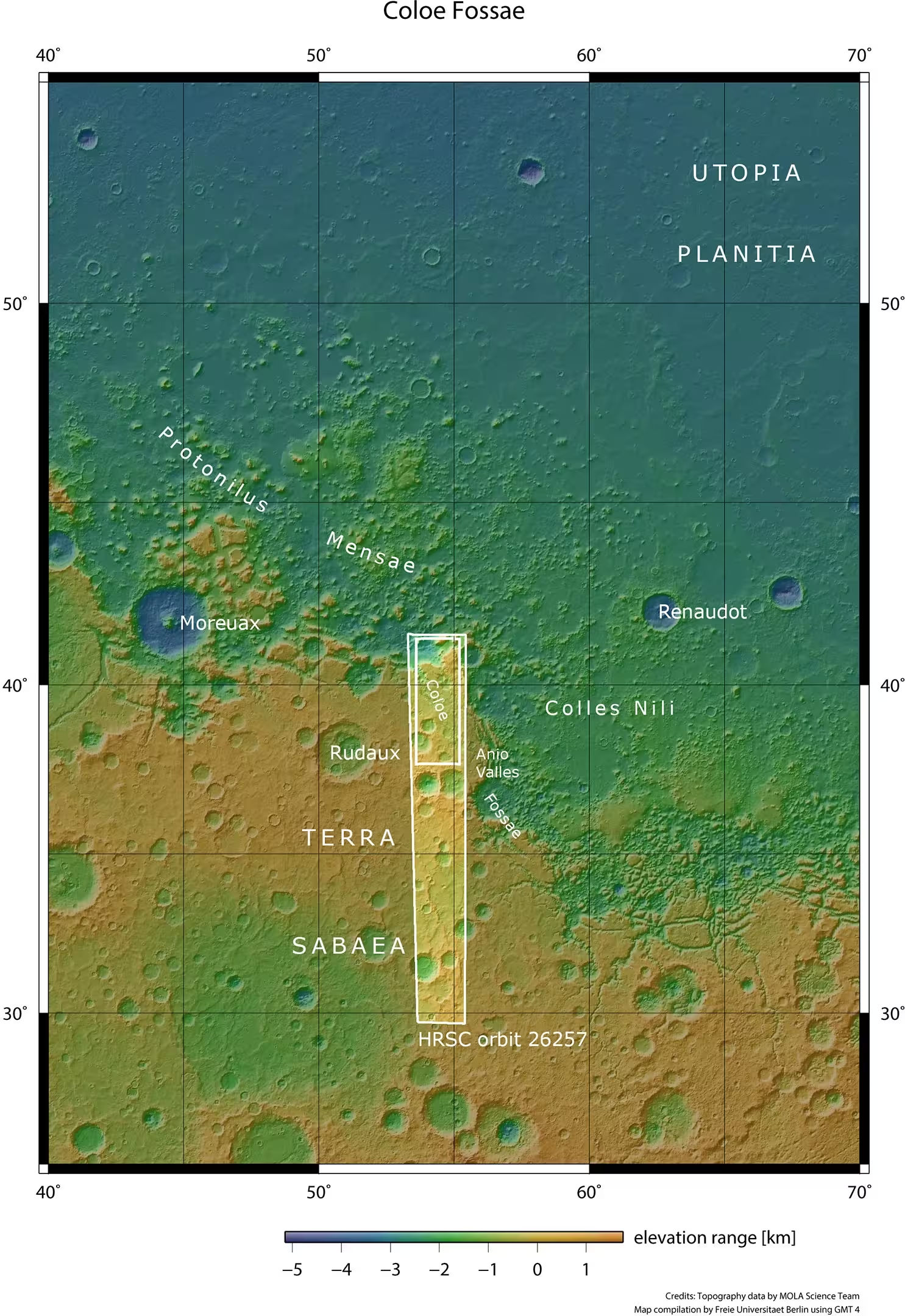

This image shows the Coloe Fossae region of Mars in wider context. It shows the divide between the northern lowlands and southern highlands of Mars. This divide wraps around the entire planet; in some places it’s marked by a sharp, two-kilometer-high cliff-face, while in others – such as here – it’s more of a broad, broken-up transitional zone (known as Protonilus Mensae). The blue area covering the upper half of the frame is the start of lowlands, which cover much of the northern hemisphere. The yellow-orange area below is the start of highlands, which cover the southern hemisphere. The area outlined by the larger white box indicates the area imaged by the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) aboard ESA’s Mars Express orbiter on October 19, 2024 (orbit 26257), while the smaller white box within shows the part of the surface featured in new images released in November 2025. Credit: NASA/MGS/MOLA Science Team

Mars’s Tilt: The Engine Behind Ancient Ice Ages

Unlike Earth, where the Moon helps stabilize axial tilt, Mars’s obliquity varies widely over geologic time. These tilt cycles have a powerful influence on climate: at higher obliquities, polar ice becomes unstable and sublimates, while mid-latitudes can accumulate seasonal and longer-term ice deposits. During lower obliquity phases, ice returns to the poles.

The Coloe Fossae features—spread around 39°N latitude—are compelling because they show ice-related deposits far from the present-day polar caps. The pattern of lineated valley fill and concentric crater fill across the mid-latitudes indicates repeated glacier expansion and retreat. Some studies suggest the most recent significant mid-latitude glaciation on Mars may have ended as recently as a few hundred thousand years ago, making these deposits among the youngest large-scale ice records on Mars.

This color-coded topographic image shows the Coloe Fossae region of Mars. It was created from data collected by ESA’s Mars Express on October 19, 2024 (orbit 26257) and is based on a digital terrain model of the region, from which the topography of the landscape can be derived. Lower parts of the surface are shown in blues and purples, while higher altitude regions show up in whites and reds, as indicated on the scale to the top right. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

Why These Discoveries Matter

Understanding where and when ice accumulated on Mars informs several scientific and practical questions. First, it refines our picture of Mars’s climate history and the pace of its environmental change. Second, buried ice represents a potential reservoir of water that could be relevant for future robotic or human missions. Third, the presence and preservation of ice-related sediments could affect searches for preserved organic matter or biosignatures—if any ever existed—because ice can both protect and alter chemical signatures over time.

Moreover, mapping the boundary between Mars’s northern lowlands and southern highlands—especially transitional zones such as Protonilus Mensae—helps scientists link surface morphology with past climate models. These maps, built from stereo and colour channels, give researchers the topographic context needed to interpret flow patterns and estimate the relative ages of deposits compared to heavily cratered highlands.

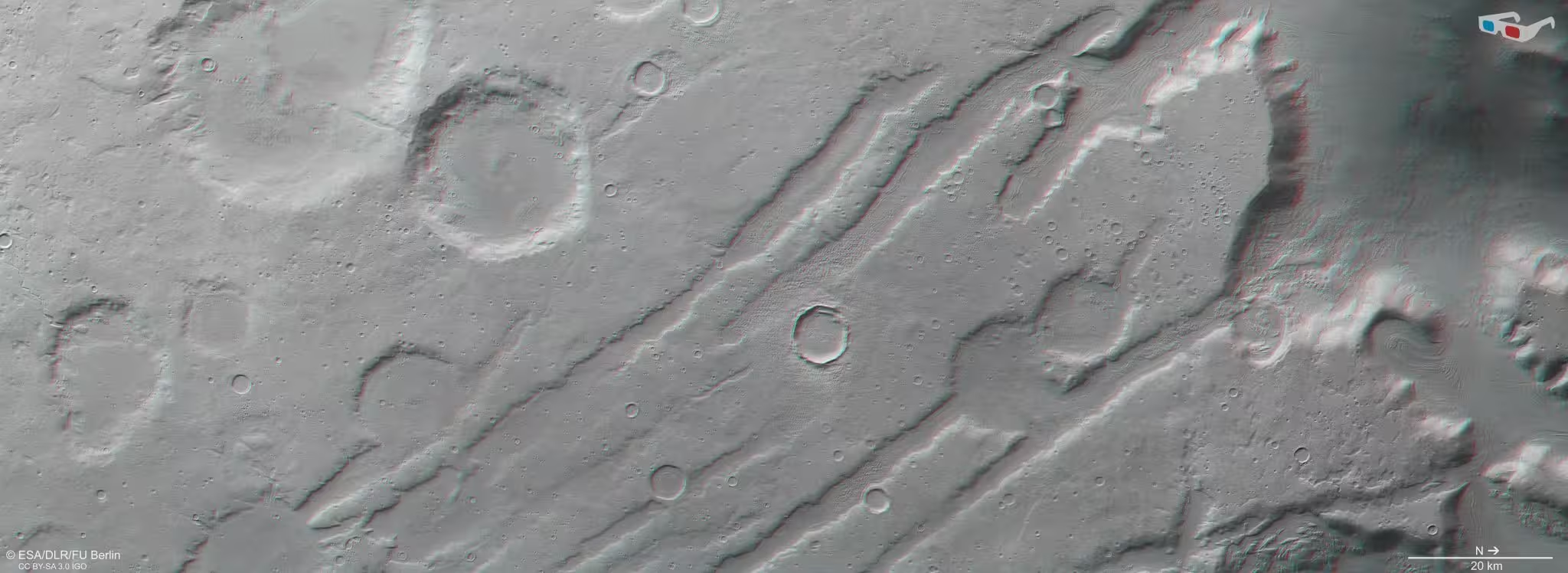

This stereoscopic image shows Coloe Fossae on Mars. It was generated from data captured by the High Resolution Stereo Camera on ESA’s Mars Express orbiter on October 19, 2024 (orbit 26257). The anaglyph offers a three-dimensional view when viewed using red-green or red-blue glasses. Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

Mission Notes: How the Images Were Produced

The imagery comes from the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on ESA’s Mars Express. Developed and operated by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), HRSC captures stereo, colour and nadir channels that are processed into digital terrain models and high-detail image products. Systematic processing of HRSC data is carried out at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof, with final image products produced in collaboration with the Planetary Science and Remote Sensing group at Freie Universität Berlin.

Expert Insight

“These images are a powerful reminder that Mars’s climate has been dynamic and regionally complex,” says Dr. Laura Mendes, a planetary geologist (fictional) who specializes in icy processes on terrestrial planets. “Lineated valley fill and concentric crater fill are not mere curiosities—they’re a record of how orbital cycles redistributed ice across Mars. That record helps us test climate models and identify places where preserved ice might still be accessible beneath thin covers of debris.”

The new HRSC datasets from October 19, 2024 (orbit 26257) and the processed releases in November 2025 add clarity to the timing and extent of these glacial episodes. Researchers will combine these observations with crater-count dating, subsurface radar, and climate simulations to refine estimates of when ice advanced into the mid-latitudes and how long it persisted.

Next Steps and Broader Implications

Future work will integrate these high-resolution visual and topographic maps with subsurface sounding instruments (such as MRO’s SHARAD) and thermal data to better constrain ice thickness and burial depth. As models of Mars’s obliquity history improve, scientists will be able to correlate specific glacial deposits with modeled climate intervals, building a more complete timeline of martian ice ages.

Beyond pure science, these findings inform mission planning. Mid-latitude regions with buried glacier deposits could be strategic targets for missions seeking water resources or cold-preserved materials. The new images of Coloe Fossae therefore contribute to both our basic understanding of Mars’s past and to practical assessments for future exploration.

The Mars Express High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) was developed and is operated by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR). The systematic processing of its data took place at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof. The working group of Planetary Science and Remote Sensing at Freie Universität Berlin created the final image products presented here.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

Interesting images, but feels a bit overhyped. Ice redistribution seems plausible, yet the age estimates? Need more radar + modeling. photos are sweet tho

mechbyte

Is this even legit? looks like glacial flows but could wind or lava mimic those patterns? need SHARAD crosschecks pls.. crater dating can be misleading

astroset

wow, Mars had glaciers that close to the equator? mind blown. pics show flow-like grooves, ridges and crater fills, looks legit though curious about the exact dating, crater counts, radars etc. epic visuals

Leave a Comment