5 Minutes

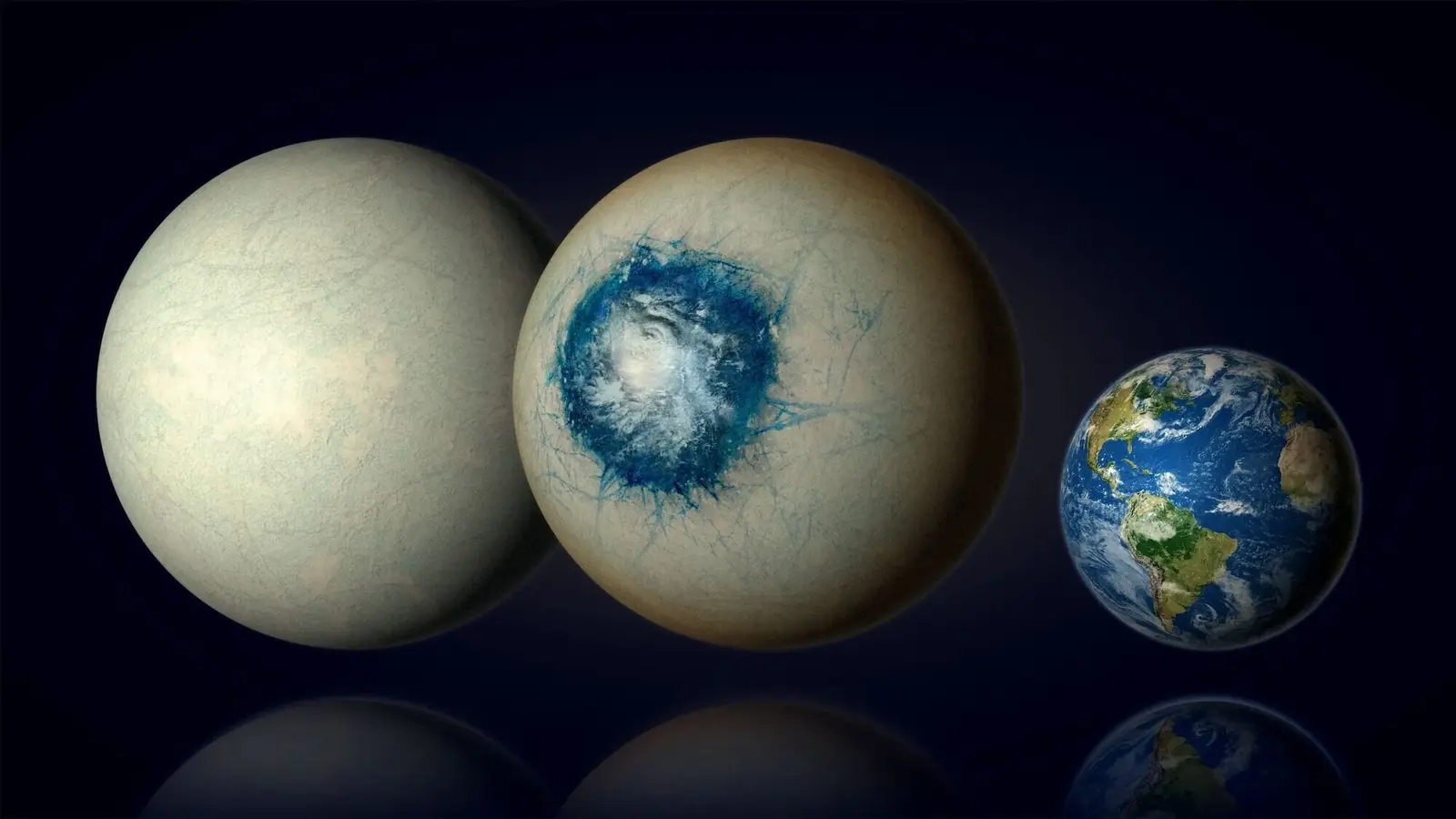

Astronomers have long worried that wild stellar behavior — flares, spots and magnetic storms — can strip atmospheres and dry out planets that otherwise sit in a star's habitable zone. A new analysis of nine exoplanets and their active host stars offers fresh, cautious optimism: variability alone appears to have limited impact on a planet’s equilibrium temperature and, under many conditions, may not prevent water from surviving on worlds near the inner edge of habitability.

Why stellar variability matters for exoplanet habitability

Star variability describes changes in a star’s brightness, magnetic field and high-energy output over time. For planets, especially rocky ones close to their stars, those changes can alter surface conditions, drive atmospheric chemistry, and in extreme cases strip atmospheres through intense ultraviolet (UV) and particle radiation. The most extreme examples come from M-type (M-dwarf) stars — small, cool, and long-lived — which frequently show powerful flares and large magnetic activity. Because M-dwarfs are abundant in the galaxy and produce many detectable planets, understanding how their variability affects habitability is a top priority in exoplanet science.

The study: nine worlds tested against active stars

Accepted to The Astronomical Journal, the recent study examined nine exoplanets orbiting stars with elevated variability. The sample spans a range of stellar types and distances: TOI-1227 b (328 ly), HD 142415 b (116 ly), HD 147513 b (42 ly), HD 221287 b (182 ly), BD-08 2823 c (135 ly), KELT-6 c (785 ly), HD 238914 b (1,694 ly), HD 147379 b (35 ly) and HD 63765 b (106 ly). Stellar masses in the sample range from about 0.17 to 1.25 solar masses and include M-, K-, G- and F-type hosts. By comparing measured flux variations from stellar activity with orbital factors like eccentricity, the team evaluated how much a star’s variability changes an exoplanet’s equilibrium temperature — the theoretical temperature a planet would have if it didn't redistribute heat internally.

Key findings: small temperature changes, water can persist

Contrary to some expectations, the researchers found that, for this set of systems, stellar variability produced only modest changes in equilibrium temperature. In other words, fluctuations in a star’s output caused only small swings in the baseline temperature estimate for these planets. Crucially, the analysis suggests that planets orbiting near the inner boundary of the habitable zone can still retain water despite host-star variability — provided other factors (atmosphere, magnetic field, and orbital dynamics) are favorable.

What equilibrium temperature actually means

Equilibrium temperature is a simplified measure: it assumes a planet absorbs and re-emits stellar energy without internal heat transfer, clouds, or greenhouse effects. Real-world surface temperatures depend heavily on atmosphere composition and circulation, so a small change in equilibrium temperature does not automatically doom a planet’s habitability.

Why M-dwarfs remain a mixed bag

M-type stars dominate the galaxy by number and can live for trillions of years — vastly longer than Sun-like stars. That longevity makes them attractive targets for the search for life. But their propensity for intense magnetic activity, UV bursts and frequent flares raises legitimate concerns. Famous nearby examples include Proxima Centauri (4.24 ly) and TRAPPIST-1 (≈39.5 ly). Both are highly active: Proxima Centauri’s single known rocky planet faces a harsh radiation environment, while TRAPPIST-1’s seven rocky planets include at least one that still appears marginally capable of holding water when other conditions are right.

Implications and next steps for exoplanet surveys

The study’s authors emphasize that this work is an incremental advance. Their models assume stellar variability operates on timescales and amplitudes that can be compared to orbital effects; longer or more extreme events could still change the picture. The takeaways are practical: (1) star variability should be included when prioritizing targets for follow-up atmospheric characterization, and (2) discovering atmospheric signatures (water vapor, ozone, greenhouse gases) remains essential to judge true habitability.

Expert Insight

"This research helps separate the headline-grabbing fear that every flare equals a dead planet from a more nuanced reality," says Dr. Maya R. Singh, an astrophysicist who studies star–planet interactions. "Stellar activity matters, but atmosphere and magnetic shielding can dramatically change outcomes. Future telescopes that can observe atmospheric escape and surface conditions will decide which worlds are truly resilient."

What to watch next

Progress will hinge on three developments: expanded monitoring of variable stars to catalogue flare statistics, more discoveries and precise characterizations of planets around active hosts, and next-generation space and ground telescopes capable of detecting atmospheric constituents. Missions like JWST and upcoming ELTs (Extremely Large Telescopes) will test whether water signatures survive in the atmospheres of planets around volatile stars. Until then, the picture remains cautiously hopeful: variability complicates the story but does not automatically close the door on habitable conditions.

Source: universetoday

Comments

skyspin

wow, kinda hopeful! still nervous about M-dwarfs tho, their flares sound brutal. If JWST finds water that will be wild

astroset

If variability only nudges equilibrium temp a bit, cool, but is that enough long term? extreme flares, CMEs, cumulative loss over Gyrs... curious.

Leave a Comment