7 Minutes

Younger women are accounting for a surprisingly large share of breast cancer cases—and many of those tumors are biologically aggressive. New regional data covering an 11-year span show that nearly one-quarter of breast cancers occurred in people aged 18–49, challenging age-based screening assumptions and arguing for earlier, risk-focused evaluation.

What the data show: a persistent signal under age 50

Researchers reviewing records from seven outpatient breast centers in western New York found 1,799 breast cancers diagnosed in 1,290 women between the ages of 18 and 49 over 2014–2024. That translated to roughly 145–196 diagnoses per year in this age range. The average age at diagnosis was 42.6 years, with cases as young as 23.

Crucially, although women under 50 made up only about 21–25% of the screened population each year, they consistently represented about 20–24% of all cancers detected. In plain terms: younger patients are a steady, disproportionate share of the disease burden.

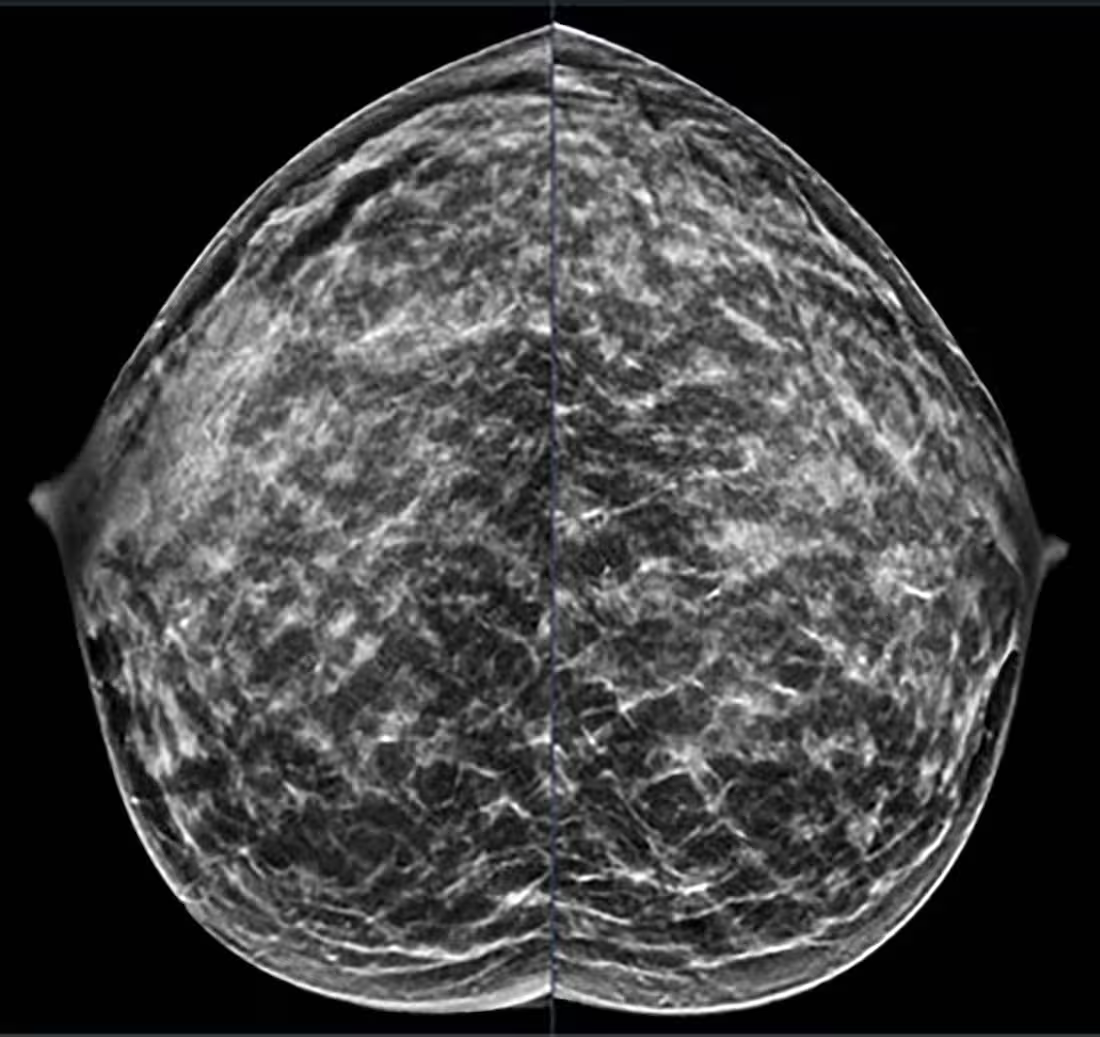

40-year-old patient presents for routine screening. Family history of paternal grandmother age 55. Extremely dense breast tissue is noted on mammography right and left craniocaudal (taken from the top of the breast) view. Credit: Stamatia Destounis, M.D., and RSNA

Tumor biology matters: many younger patients present with invasive, aggressive cancers

The review found that 80.7% of cancers in the cohort were invasive and 19.3% non-invasive. Most were detected via diagnostic workup (59%) rather than routine screening (41%). Among the cancers in younger women, a higher proportion showed aggressive features—some were triple-negative, a subtype that does not respond to hormone or HER2-targeted therapies and is associated with poorer short-term prognosis.

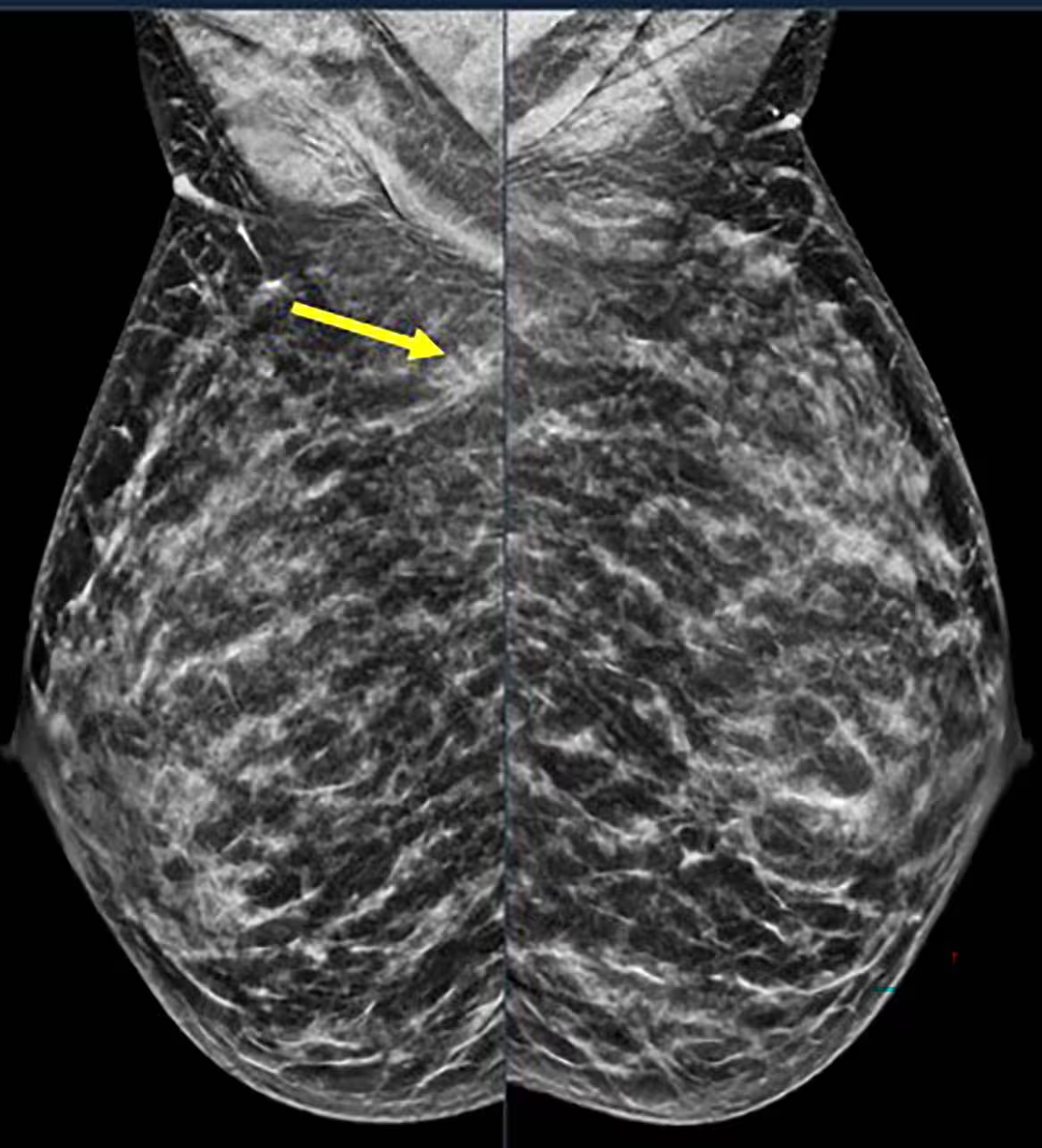

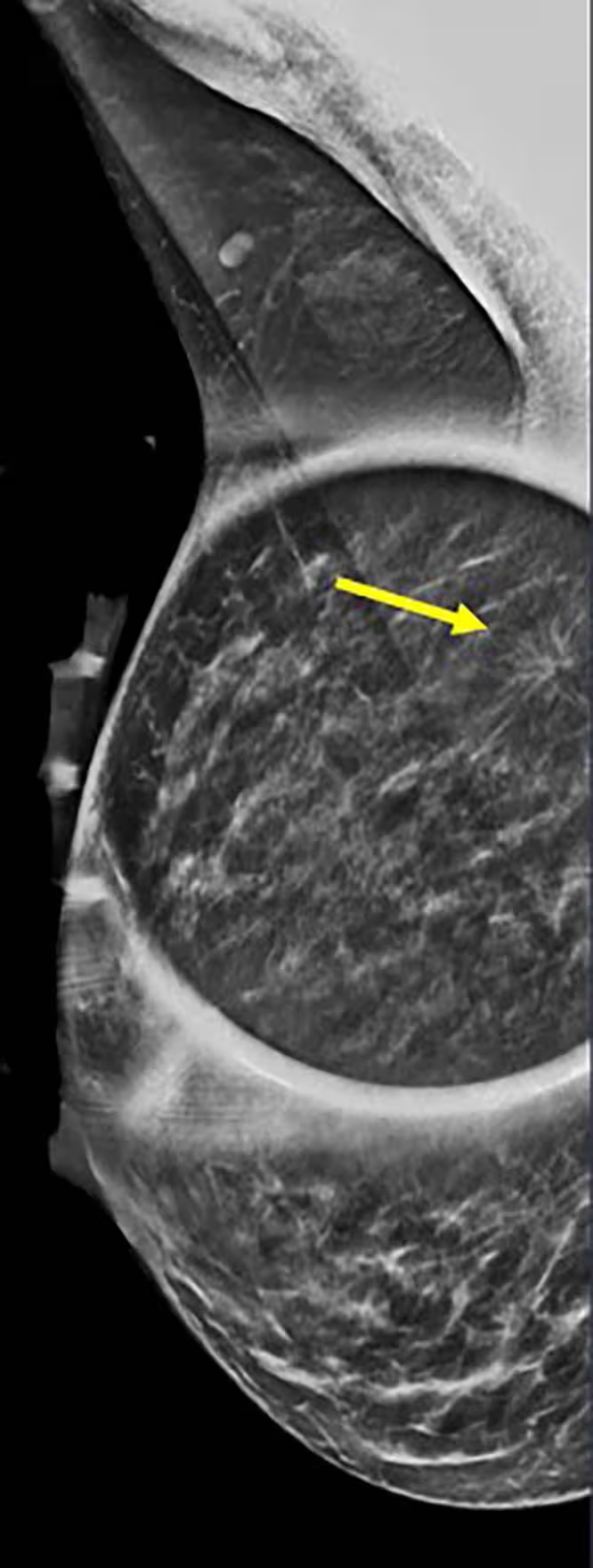

Spot on right mediolateral oblique (side angle) view. Area of distortion persists on additional mammographic views, and a mass is identified on subsequent breast ultrasound. Ultrasound guided biopsy was performed and revealed nuclear grade 1 invasive ductal carcinoma. Credit: Stamatia Destounis, M.D., and RSNA

Why these findings challenge age-only screening rules

Current major screening recommendations differ by organization. For average-risk women, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) suggests biennial mammography starting at age 40; the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends annual screening from 45 with the option to start between 40 and 44. For those at elevated genetic or familial risk, annual MRI plus mammography may begin at about age 30.

But the new regional analysis underlines a blind spot: when age is the primary gatekeeper for screening, younger people with significant risk factors or aggressive tumor biology may be missed or diagnosed later. The stable annual counts of cancer in younger patients throughout the 11-year period mean this is not a transient blip—it’s an enduring pattern that merits action.

How researchers gathered and interpreted the data

The study team, led by radiologist Stamatia Destounis, M.D., and EWBC research manager Andrea L. Arieno, B.S., reviewed clinical imaging reports from seven outpatient centers across a roughly 200-mile region in western New York. They deliberately excluded non-primary breast cancers and classified cases by detection method (screening vs diagnostic), tumor type (invasive vs non-invasive), and tumor biology (e.g., hormone receptor status).

That approach allowed the investigators to track how often cancers appeared in younger patients, how they were found, and which tumor subtypes were most common. It also enabled analysis of trends across age subgroups within the 18–49 bracket.

40-year-old patient presents for routine screening. Family history of paternal grandmother age 55. Extremely dense breast tissue is noted on mammography right and left mediolateral oblique (side angle) view. In addition, an area of architectural distortion is seen at the posterior right breast on right view (see arrow). Credit: Stamatia Destounis, M.D., and RSNA

Implications for clinical practice and patients

The study’s message is straightforward: age alone should not be the sole determinant of screening strategy. Physicians caring for reproductive-age and younger adult patients should take detailed family and personal histories, assess breast density, consider genetic testing when appropriate, and perform individualized risk assessments.

For patients with a strong family history, known genetic mutations (for example, BRCA1/2), and some minority groups who show higher risk at younger ages, earlier and more intensive screening—including breast MRI in addition to mammography—may be lifesaving.

Practical steps could include earlier clinical breast exams, shared decision-making conversations about the pros and cons of starting mammograms before routine guideline ages, and ensuring that younger patients know the warning signs of breast cancer—new lumps, skin changes, nipple discharge, or persistent localized pain.

Public health and research angles

At a population level, stable incidence of breast cancer in younger women suggests that healthcare systems should not treat this as an occasional exception. Rather, policy-makers and clinical guideline committees may need to revisit screening thresholds and risk stratification tools to better capture younger high-risk groups.

Research priorities include refining risk models that combine genetics, family history, breast density, race/ethnicity, reproductive history, and lifestyle factors; evaluating the cost-effectiveness of earlier MRI or supplemental ultrasound for dense breasts in younger adults; and improving outreach to communities with known disparities in early-age breast cancer.

What patients should take away

- Breast cancer is not only a disease of older age—women under 50 represent a consistent share of diagnoses.

- Many tumors in younger patients are invasive and can be aggressive; earlier detection improves treatment options.

- If you have a family history or known genetic risk, speak with your clinician about earlier and more intensive screening.

- Know your breasts: report new lumps, changes in shape or skin, or abnormal discharge promptly.

Expert Insight

“These findings reinforce what we’ve been seeing in larger datasets: younger patients shouldn’t be dismissed as low risk by virtue of their age alone,” says Dr. Maya Sullivan, a breast imaging specialist and science communicator. “Risk assessment tools are improving, and clinicians need to use them proactively—especially for patients with dense breasts or a family history. Earlier personalized screening can change the trajectory for many individuals.”

Dr. Sullivan’s point highlights a practical tension: broader screening catches more cancers earlier, but it also increases false positives and downstream testing. The key is targeted screening—identifying who among younger adults truly benefits from intensified surveillance.

Next steps and future prospects

Clinics and research centers should continue to collect granular data on tumor biology, detection method, and patient demographics to refine screening recommendations. Artificial intelligence and risk-prediction algorithms may eventually help clinicians personalize screening schedules—integrating imaging features like breast density with genetic and clinical data to create adaptive screening plans.

Meanwhile, public education campaigns can remind younger adults that breast cancer is not only an older person’s disease and that awareness and early action matter. For individuals with suspected elevated risk, early referral to a specialized genetics or high-risk breast clinic is a practical pathway to more tailored surveillance.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Reza

Is this just WNY though? 7 centers is useful but can we generalize nationwide? Curious about race, income, genetics breakdown. Sounds important but need bigger studies, right?

bioNix

Whoa, thats alarming. Younger women ~25% of cases? Dense breasts + family history = recipe for missed cancers. Docs gotta rethink who's screened. My friend was 37 when found, lucky we pushed for tests

Leave a Comment