5 Minutes

New deep-sea drilling in the South Atlantic has revealed that broken lava deposits on the seafloor lock away far more carbon dioxide than scientists expected. These porous rubble layers, known as lava breccia, become natural carbon sponges as seawater moves through and mineralises within them.

How rubble on the seafloor becomes a long-term carbon store

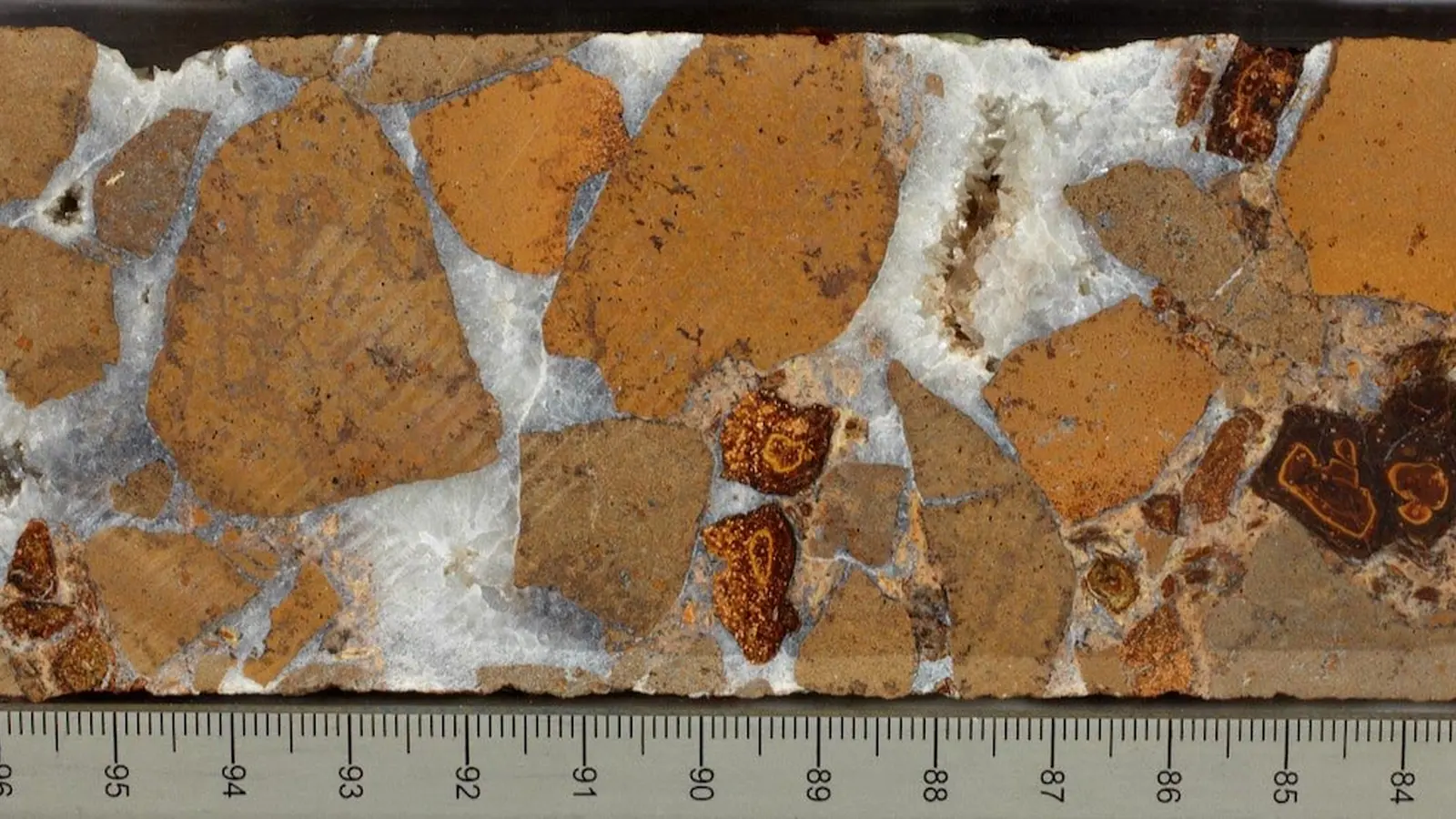

Imagine piles of volcanic rubble slowly sliding down the flanks of an underwater mountain. Over millions of years, those fragments—called breccia—are transported and buried on the seafloor. When seawater percolates through the porous pile, it reacts with the volcanic rock and drives chemical reactions that lock CO2 into solid minerals, notably calcium carbonate.

Researchers from the University of Southampton analysed sixty-million-year-old cores drilled from deep under the South Atlantic Ocean to quantify how much carbon this process captures. The material came from International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 390, including sampling at Site U1557 on board the research vessel Joides Resolution.

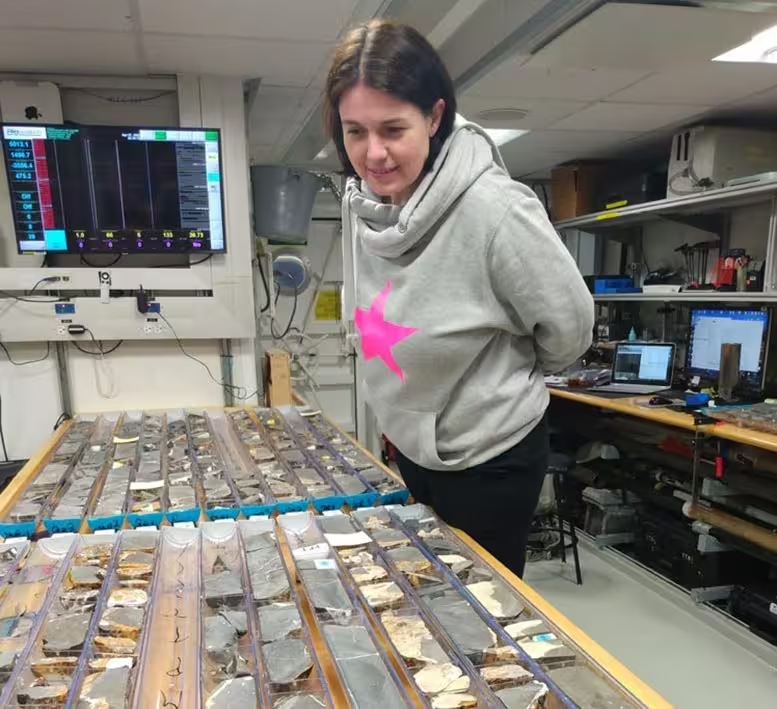

Dr. Rosalind Coggon examining cores of upper ocean crust lavas cored during IODP Expedition 390. Credit: Alyssa Stephens, IODP JRSO

What the drilling found—and why it surprised scientists

Mineralogical analysis and geochemical measurements show that these breccia deposits contain between two and forty times more CO2 than previously sampled, intact lava flows. The reason: breccia is both porous and permeable. Its pore spaces let seawater circulate for millions of years, allowing carbonate minerals to precipitate and effectively cement the rubble while trapping dissolved inorganic carbon.

As Dr. Rosalind Coggon, lead author and Royal Society Research Fellow at the University of Southampton, explained: 'We recovered the first cores of this material after it has spent tens of millions of years being rafted across the seafloor. These porous, permeable deposits have the capacity to store large volumes of seawater CO2 as they are gradually cemented by calcium carbonate minerals.'

Scientific context: The long-term carbon cycle and mid-ocean ridges

The long-term carbon cycle controls atmospheric CO2 on geological timescales by exchanging carbon among Earth’s interior, the oceans, and the atmosphere. Mid-ocean ridges—where tectonic plates diverge and new ocean crust forms—produce vast quantities of basaltic rock. As newly formed crust cools and fractures, seawater penetrates the rock, promoting reactions that move elements and carbon between ocean and lithosphere.

Until now, most attention focused on intact basaltic crust and alteration within sheeted and massive flows. This study highlights that breccia generated by erosion on ridge flanks is a previously underappreciated reservoir. In effect, the rubble behaves like a sponge and a slow chemical factory: seawater delivers dissolved CO2, and mineral precipitation locks it away as carbonate over millions of years.

Research vessel Joides Resolution. Credit: Dr. Rosalind Coggon

Implications for climate history and carbon budgets

Finding that breccia can hold substantially more CO2 affects how geoscientists estimate the solid-Earth sink for carbon. If widespread, these deposits could alter reconstructions of past atmospheric CO2 and help refine models of how Earth regulated climate through deep time. That matters when researchers compare rates of volcanic CO2 release at ridges with the ocean's capacity to remove and store that carbon geologically.

Beyond paleoclimate, the discovery refines baseline knowledge needed for any future consideration of subsurface or geological carbon sequestration analogues. The natural process—seawater-driven mineralisation in permeable rock—offers a real-world example of efficient long-term carbon fixation.

What the expedition involved

- Drilling and coring at IODP Site U1557 during Expedition 390, sampling upper ocean crust and associated breccia.

- Petrographic and geochemical analyses to quantify carbonate content and estimate CO2 storage.

- Comparative assessment against previously sampled intact lavas to measure the increase in stored carbon (2–40x).

Expert Insight

'This discovery fills an important gap in our understanding of seafloor carbon sinks,' says Dr. Maya Singh, marine geochemist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 'Breccia layers are heterogeneous and often overlooked, yet they offer extensive pore networks where mineralisation can proceed over geological timescales. Incorporating them into global carbon budgets will sharpen our view of Earth's long-term climate regulation.'

As scientists continue to map ocean crust alteration and quantify mineralised carbon, these rubble reservoirs will be a critical piece of the puzzle—reminding us that small fragments of rock, given time and chemistry, can store enormous amounts of carbon.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

coinflux

Is this for real? 2-40x more CO2 sounds huge, but sampling bias? need more sites, stats, pls show error bars

geolook

Wow, ocean rubble locking CO2 away? That's wild. If breccia really stores that much, paleo CO2 curves need tweaking. Curious about how widespread tho, and rates over time...

Leave a Comment