5 Minutes

A long-running shingles vaccination program in Wales has produced surprising results: researchers now link the jab not only to fewer new dementia cases but also to slower decline and lower dementia-related mortality in people already diagnosed. The findings add to growing evidence that vaccines targeting nervous-system viruses could become part of dementia prevention and care strategies.

A real-world program turned into a natural experiment

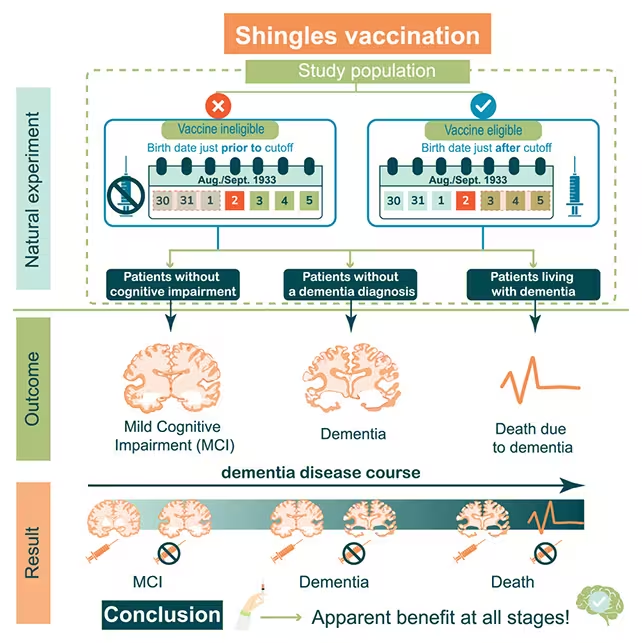

When the UK National Health Service rolled out a shingles vaccine program in Wales in 2013, a seemingly minor policy decision created a rare research opportunity. To prioritize distribution, the program offered vaccination to people aged 79 but not to those aged 80. That single-year cutoff produced two nearly identical cohorts separated by just one year of age, allowing scientists to compare outcomes while minimizing many common confounding factors such as education, long-term health status, and socioeconomic background.

Analyzing health records from that rollout, an international research team found that among 14,350 people who had already been diagnosed with dementia before the program began, those who received the shingles vaccine were almost 30 percent less likely to die of the condition over the following nine years. The same dataset also reinforced earlier results linking vaccination to lower rates of mild cognitive impairment and fewer new dementia diagnoses overall.

The vaccine protected against dementia and mild cognitive impairment.

Why this matters: prevention and possible treatment

Most dementia research focuses on prevention or slowing decline before diagnosis. These new observations suggest the shingles vaccine may do both: lower the chance of developing cognitive decline and temper progression in people who already have dementia. That dual potential—both preventive and therapeutic—has major public-health implications because the vaccine used in Wales is already inexpensive, safe, and widely available.

Cardiff University epidemiologist Haroon Ahmed notes that the vaccine's existing safety profile and availability make this an especially promising avenue for further investigation. Researchers stress, however, that observational data cannot prove causation. The Welsh rollout functioned like a randomized trial by accident, but more controlled studies will be needed to confirm how strong and direct the protective effect is.

Possible biological mechanisms

Scientists are exploring several plausible explanations for the association. Shingles is caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), which can lie dormant in nerve tissue and reactivate later in life. Viral activity in nervous tissue has been linked in animal models to the accumulation of abnormal proteins—like those seen in Alzheimer's disease—which can damage neurons and promote cognitive decline.

Other hypotheses center on immune system modulation. Vaccination could reduce neuroinflammation or alter immune responses that otherwise accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Disentangling these pathways will require laboratory studies, animal models, and prospective clinical trials that include biomarkers of neurodegeneration as well as cognitive outcomes.

What researchers want to test next

- Expand analyses to larger, more diverse populations across different age ranges to see if the protective signal holds.

- Compare the older vaccine formulation used in 2013 with newer, more effective shingles vaccines to evaluate whether updated shots provide similar or stronger protection.

- Run prospective clinical trials or nested studies that collect biological samples and imaging to probe mechanisms—viral reactivation, immune changes, and protein aggregation.

Pascal Geldsetzer, a biomedical scientist at Stanford University, describes the results as encouraging because they hint at therapeutic potential for people already living with dementia. He and other authors say the findings justify investing research resources to investigate the pathways that could link herpesvirus activity, immune response, and neurodegeneration.

Public-health implications and caution

If future trials confirm causation, shingles vaccination could become a low-cost intervention in dementia risk reduction strategies, complementing lifestyle and vascular-health approaches. For now, clinicians and policymakers should view the results as promising but preliminary: observational links can point the way, but only rigorous trials and mechanistic studies can establish medical guidelines.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Reed, a neurologist focused on neuroinfectious disease, offers a practical read: "These results are a reminder that infections and immunity matter for brain health. A widely available vaccine that reduces not only incidence but also mortality from dementia would be a game-changer—but we must test it carefully. The next steps are controlled trials and biomarker work to show whether the effect is direct or mediated through reduced inflammation or viral suppression."

In short, the Welsh program gave scientists a valuable, though imperfect, lens on how vaccines might influence brain aging. The evidence now calls for deliberate, well-funded follow-up studies to determine whether a familiar vaccine could play a new role in the fight against dementia.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Tomas

is this even true? observational studies often overstate effects. 30% fewer dementia deaths sounds huge, need RCTs and biomarkers, not convinced yet

bioNix

Wow this is wild, shingles jab linked to less dementia and slower decline? If that’s real it could change prevention big time, curious what trials show…

Leave a Comment