10 Minutes

A new, wafer-thin brain implant called BISC promises to change how humans communicate with machines. Combining extreme miniaturization, thousands of electrodes and a wireless, high-bandwidth link, this device aims to make brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) both more powerful and less invasive than ever before.

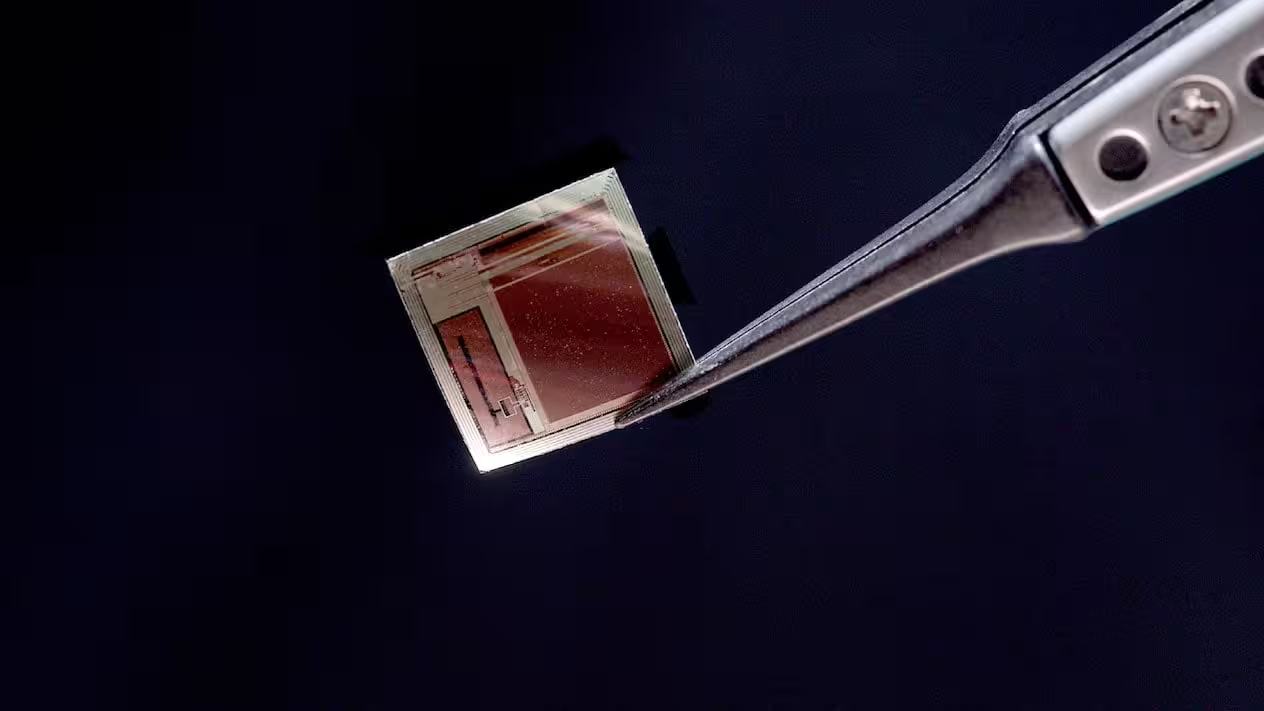

The BISC implant shown here is roughly as thick as a human hair

A startlingly small device with massive data throughput

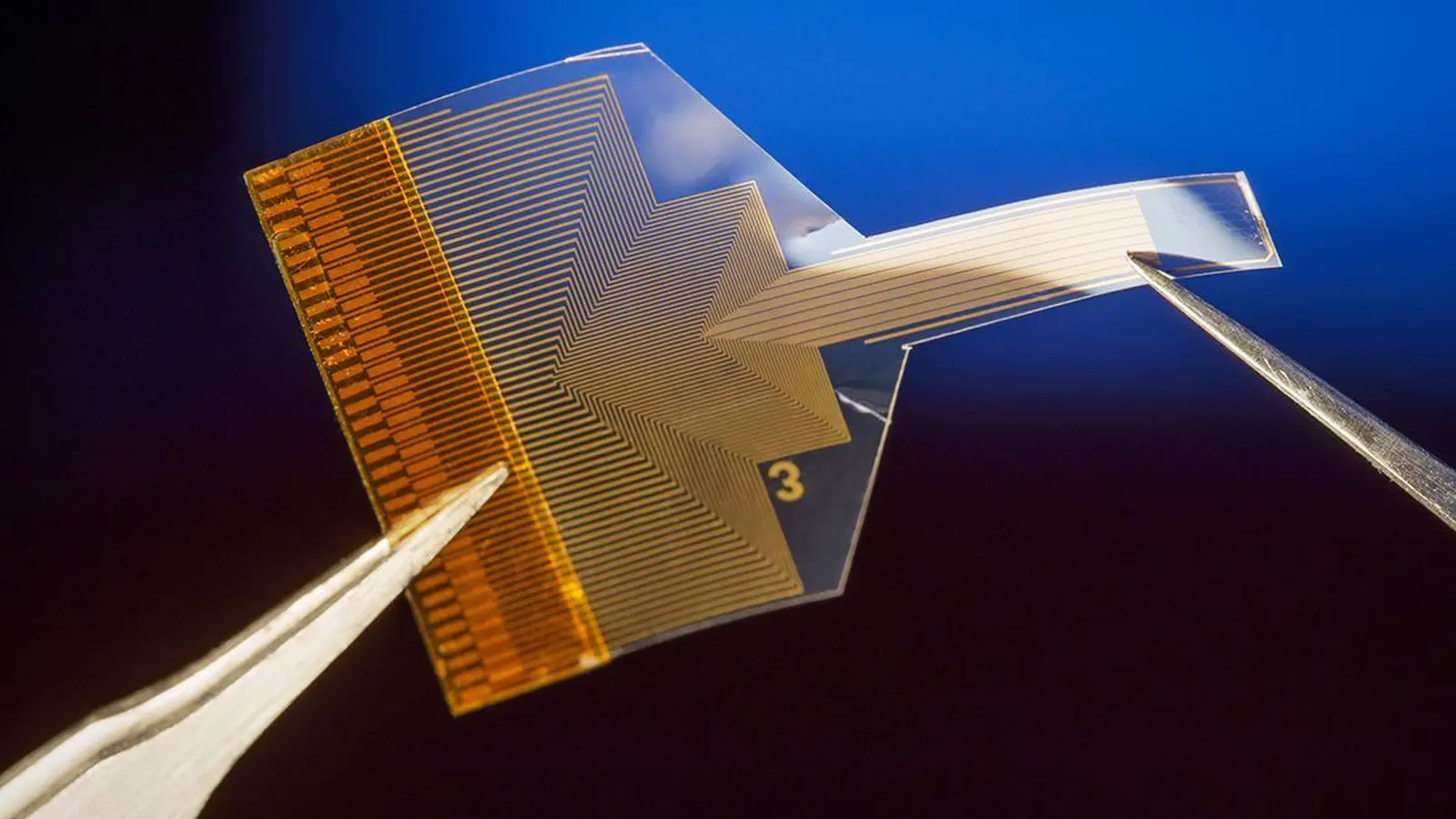

Traditional neural implants pack amplifiers, batteries and radios into bulky canisters that sit under the skin or in the chest. BISC flips that model on its head: the design compresses all essential electronics onto a single complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) chip thinned to about 50 μm. That tiny, flexible chip integrates recording and stimulation hardware, radio transceiver, power circuitry and digital control logic into a volume of roughly 3 mm³ — less than one thousandth the volume of many existing devices.

Why does size matter? Smaller devices reduce surgical trauma, lower the risk of infection, minimize tissue reaction and can be placed without removing large sections of skull. BISC’s flexible form allows it to conform to the cortical surface and rest in the subdural space with minimal disturbance. Yet despite its minimal footprint, BISC supports remarkably high data throughput — up to 100 Mbps over a custom ultrawideband link — enabling the transmission of rich neural datasets to external computers and AI systems in near real time.

How the system is organized: chip, relay and software

BISC is not a standalone chip. The platform is three-part: a single-chip implant, a wearable battery-powered relay station and a dedicated software stack. The implant houses 65,536 electrodes, 1,024 simultaneous recording channels and 16,384 stimulation channels. Because the platform relies on semiconductor foundry processes, the same manufacturing scale that makes consumer electronics cheap and plentiful can, in principle, produce many implants at high yield.

Single-chip integration

All analog front-end components, data converters, power-management circuits and a radio transceiver are fabricated directly on the chip. Integrating these functions eliminates the need for sizable implanted canisters and long tethered wiring, substantially reducing the implant’s physical profile and surgical footprint.

Wireless relay and compatibility

Outside the skull, a small wearable relay supplies power and mediates the high-bandwidth radio link between the implant and external computers. The relay behaves like an 802.11 Wi-Fi device to the outside world, effectively bridging any machine learning platform to the brain without a physical cable. This arrangement creates a practical path for pairing BISC with advanced decoding algorithms, cloud-based AI, or localized edge compute for low-latency control.

From raw signals to AI-decoded intentions

BCIs derive value from the ability to read (and sometimes write) neural activity with sufficient temporal and spatial resolution. BISC’s micro-electrocorticography (μECoG) array captures a high-density map of cortical surface potentials that, when combined with modern machine-learning models, can be decoded into intentions, sensory experiences and motor commands.

Andreas Tolias of Stanford, who collaborated on tests of BISC, emphasizes the partnership between hardware and AI: training deep-learning models on large-scale neural datasets — including recordings collected with BISC — allowed the team to evaluate how effectively this implant allows algorithms to decode neural states. In short, the system turns the cortical surface into a high-bandwidth portal for read–write communication with AI and external devices.

Clinical targets: who could benefit?

The potential clinical applications are broad. High-resolution, wireless BCIs promise improvements in managing drug-resistant epilepsy by enabling finer seizure monitoring and more targeted stimulation. For people with spinal cord injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or stroke, these interfaces could restore motor or communication abilities by decoding intended movements or speech and driving prosthetic limbs, speech synthesizers or assistive devices.

Vision restoration and sensory prostheses are other key targets. Because BISC supports both dense recording and stimulation channels, it can potentially feed patterned electrical inputs to visual cortex regions that correspond to specific percepts — a pathway toward next-generation sight-restoring implants. For patients with paralysis or locked-in states, a combination of decoding and stimulation offers pathways to regain interactive function.

Surgical approach and early testing

Moving a new implant from lab to clinic requires careful surgical design. The BISC team developed minimally invasive insertion techniques that allow the chip to be slid into the subdural space through a small opening in the skull and laid across the cortical surface. Because the device is ultra-thin and does not penetrate brain tissue, it minimizes mechanical mismatch and chronic tissue reaction, both of which can degrade signal quality over time.

Preclinical studies tested the chip in motor and visual cortices and confirmed stable recording across experimental timelines. Early short-term human recordings are underway in surgical settings to collect data on intraoperative performance and to refine protocols for safe use. Columbia neurosurgeon Brett Youngerman and epilepsy neurologist Catherine Schevon have collaborated on clinical implementation efforts, including a National Institutes of Health grant to test BISC in drug-resistant epilepsy.

Engineering trade-offs and technical innovations

Designing such a compact platform required several technical leaps. Existing BCIs often rely on separate modules: amplifiers, digitizers, radios and power management each occupy physical space. BISC consolidates these elements into a single silicon die, leveraging advances in CMOS scaling and mixed-signal design to compress many functions while controlling heat dissipation and power draw.

The chip’s ultrawideband radio and external relay are equally important: achieving 100 Mbps wireless throughput is at least two orders of magnitude better than many current wireless BCIs, and that throughput is critical for streaming dense multi-channel neural data needed by state-of-the-art AI decoders. The platform also defines a custom instruction set and software stack optimized for neural interface workloads, enabling standardized control, stimulation paradigms and compatibility with machine-learning pipelines.

Commercialization, partnerships and ecosystem

To accelerate translation beyond academic labs, the researchers spun out Kampto Neurotech, a company led by project engineer Nanyu Zeng. The startup aims to produce preclinical versions of the chip and to secure partnerships and regulatory support for human use. The project itself was incubated under DARPA’s Neural Engineering Systems Design program, which deliberately funds ambitious integrations of neuroscience, microelectronics and clinical translation.

Because BISC is built using foundry processes common to the semiconductor industry, the path to scale is clearer than for bespoke implants. Mass manufacturing could drive down unit costs and enable broader research access, accelerating innovation in decoding algorithms and neuroprosthetic applications.

Ethics, safety and real-world hurdles

Even with impressive technical specs, BISC must navigate scientific, clinical and ethical challenges. Long-term biocompatibility remains a crucial unknown: how will the subdural interface behave over years or decades? Will signal fidelity hold up as tissue response matures? Clinical trials and long-term animal studies are necessary to address these questions.

Beyond biology, societal concerns about privacy, consent and the possibility of cognitive augmentation must be considered. High-bandwidth connections between brains and AI could provide enormous therapeutic benefit, but they also raise questions about who controls neural data and how it might be used. Clear regulatory pathways, robust encryption, transparent consent and public engagement will be essential as these technologies move from lab prototypes toward clinical reality.

What BISC could mean for neuroscience and AI

BISC reframes the brain as a dense, accessible sensor network — one that can be sampled at resolutions previously reserved for large, invasive arrays. For neuroscience, that means more detailed maps of population activity across the cortex, enabling better models of perception, decision-making and motor control. For AI, it means richer training data and opportunities to develop decoders that translate neural patterns into actions or percepts.

Imagine a future operating room where a surgeon places a hair-thin chip that immediately begins streaming thousands of channels of cortical activity to a decoding engine capable of translating intention into movement or speech. That scenario remains aspirational, but BISC narrows the gap between current clinical BCIs and that future.

Expert Insight

“The novelty of BISC isn’t just that it’s thin — it’s that it integrates so much capability into a single, manufacturable piece of silicon,” says Dr. Maya Hollis, a fictional neuroengineer and science communicator with experience in medical device startups. “High channel counts and wireless bandwidth are game-changers because they let researchers and clinicians work with richer neural representations. But the real test will be durability and safety in chronic human use. That’s where careful trials and transparent reporting matter most.”

Dr. Hollis’s perspective underscores the balance needed between engineering ambition and clinical caution: pushing technical boundaries must be matched by rigorous evaluation of patient safety and real-world benefit.

Looking ahead

BISC represents a bold direction for brain–computer interfaces: instead of scaling devices by adding external modules or bulky implants, it compresses functionality into an ultra-thin, mass-manufacturable chip while pairing that hardware with high-bandwidth wireless links and advanced software. The potential clinical impacts — from epilepsy management to motor restoration, communication aids and sensory prostheses — are significant.

Still, the path from promising preclinical results and short-term intraoperative recordings to chronic, approved human implants demands time, data and oversight. If BISC’s early promise holds up in extended human studies, we may be watching a turning point: a new class of brain interfaces that make seamless, practical connections between human brains and AI systems both possible and safe.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

skyspin

Promising tech, feels a bit overhyped. manufacturing scale ok but clinical years away, if that's real then...

bioNix

Is this even safe long-term? Microchip on cortex sounds neat but what about scarring, encryption, who owns the data... big questions

atomwave

Wow, a hair-thin chip streaming thousands of brain channels at 100 Mbps? feels like sci-fi, but kinda unreal, nervous lol

Leave a Comment