6 Minutes

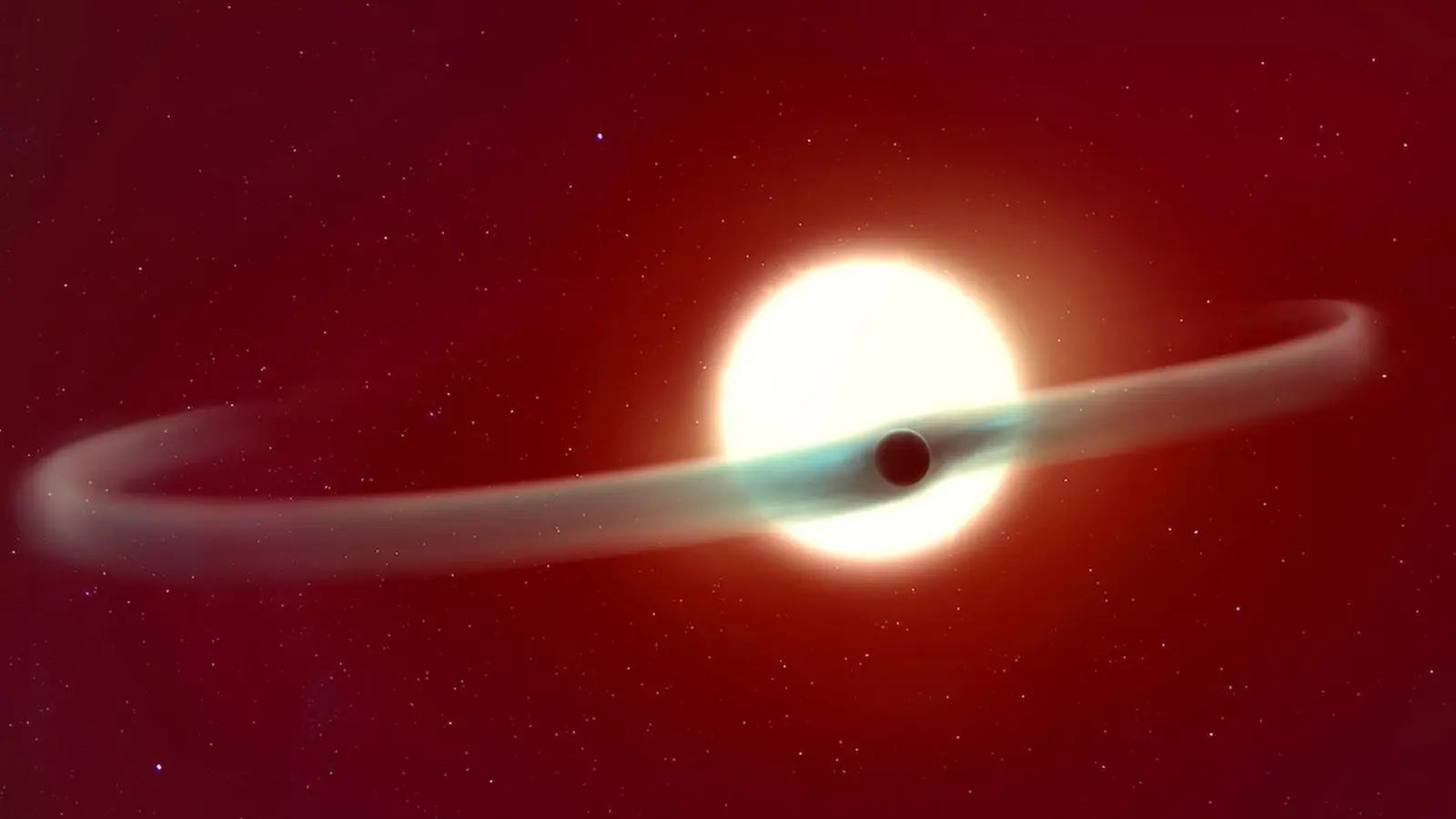

About 880 light-years away a scorched gas giant is literally pouring part of itself into space. New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope reveal that WASP-121b (nicknamed Tylos), an ultra-hot Jupiter, is trailing not one but two enormous tails of helium that span nearly 60 percent of its orbit. This continuous view of atmospheric escape offers the clearest picture yet of how hostile stellar environments can strip a planet’s atmosphere.

A comet-like spectacle: what JWST actually saw

WASP-121b is an extreme world. About the size of Jupiter but orbiting so close to its star that a year lasts roughly 30 hours, the planet bakes under intense stellar radiation. That energy heats the upper atmosphere to thousands of degrees and drives lighter gases like hydrogen and helium to escape. Astronomers have seen signs of atmospheric loss before, usually as brief signals during a planet’s transit across its star. But the new JWST data cover more than one full orbit — nearly 37 continuous hours — allowing scientists to track the escape process over time.

Using JWST’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS), the team scanned for helium absorption lines in the near-infrared. Helium absorption is a reliable tracer of atmospheric outflow because excited helium atoms absorb infrared light at specific wavelengths. The result: a persistent, large-scale helium haze that occupies almost 60 percent of WASP-121b’s orbital path. Rather than a compact cloud, the escaping gas forms elongated structures — two distinct tails — one trailing the planet and one extending ahead of it along the orbit.

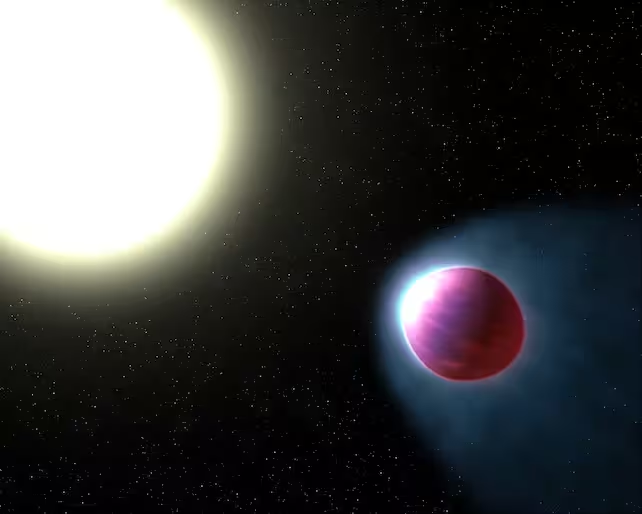

An illustration of exoplanet WASP-121b, or Tylos, and its star

Why two tails are a surprising puzzle

Most models of atmospheric escape predict a single stream of gas shaped by the planet’s motion, the push of stellar radiation, and the ram pressure of the stellar wind. WASP-121b’s twin tails complicate that picture. The trailing tail fits conventional expectations: stellar radiation and the combined orbital motion sweep material back into a wake. The leading tail, however, implies material is being pulled or redirected in the direction of the planet’s motion — perhaps under the influence of the star’s gravity or complex interactions with the stellar wind and magnetic fields.

Current 1D or simplified 3D simulations struggle to produce two large, long-lived tails separated in the way JWST observed. The data suggest a richer three-dimensional geometry: expanding gas launched from the dayside, accelerated and ionized by stellar photons, then sculpted by competing forces. The helium structures together cover an area more than 100 times the diameter of the planet, marking one of the largest continuous detections of atmospheric escape to date.

Scientific context and implications for planetary evolution

Atmospheric escape matters because even slow leaks, sustained over millions or billions of years, can transform a planet. For smaller worlds, losing a hydrogen-helium envelope can convert a sub-Neptune into a rocky super-Earth. For giant planets like WASP-121b, mass loss can alter atmospheric chemistry and structure, possibly exposing deeper layers or changing observable signatures such as metal vapor clouds and high-speed winds.

WASP-121b is already known for exotic weather — vaporized metals, ruby- and sapphire-like condensates, and blistering jet streams. The discovery of extended helium tails adds another layer: stellar irradiation not only sculpts the upper atmosphere but can fling large quantities of light gas into circumstellar space. Understanding the fate of that gas — whether it dissipates into the star’s environment, forms transient circumstellar structures, or is recycled — requires more sophisticated 3D magnetohydrodynamic and radiation-hydrodynamic models.

What the JWST observation adds

- Unprecedented continuous coverage along >1 orbit (≈37 hours) using JWST NIRISS.

- Clear detection of helium absorption stretching across ≈60% of the planet’s orbit.

- Identification of two spatially distinct helium tails, raising new questions about star–planet interactions.

- Direct observational constraints for future 3D simulations of atmospheric mass loss.

Expert Insight

“This observation changes how we must think about atmospheric escape,” says Romain Allart of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets and Université de Montréal, who led the study. He notes that continuous, full-orbit monitoring was the key to revealing structures that brief transit snapshots miss.

Dr. Elena Ruiz, an astrophysicist who studies star–planet interactions, adds in a fictional but realistic commentary: “Seeing two helium tails of this scale is like watching a planet leave fingerprints all around its star. It forces modelers to include 3D flows, stellar gravity, and magnetic effects simultaneously. JWST has opened a window on processes that dictate how planets age, migrate, and — in extreme cases — are stripped down to their cores.”

Next steps and future prospects

Researchers will use these JWST results to refine simulation codes and plan follow-up observations. Multi-wavelength campaigns — combining infrared helium searches with ultraviolet observations of hydrogen and metal lines — can map the full composition of escaping gas. Monitoring other ultra-hot Jupiters over full orbits will reveal whether twin-tail morphologies are rare curiosities or an overlooked common outcome of intense star–planet interaction.

The study, published in Nature Communications, is a reminder that exoplanets are dynamic systems. With JWST and future observatories, astronomers will increasingly capture planets in the act of changing, offering direct evidence of the processes that sculpt worlds beyond our solar system.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

RaZoM

Is this even true? Two helium tails spanning 60% of the orbit sounds cinematic. Could stellar activity or instrument effects mimic that, or is it real? idk...

astroset

Wow that's wild! A planet literally leaking helium like a comet tail... mind blown, JWST is insane. But why two tails? magnetic fields? stellar wind? so cool but weird.

Leave a Comment