6 Minutes

For decades doctors relied heavily on cholesterol panels to estimate a patient’s risk of heart attack and stroke. New evidence, however, elevates inflammation — measured by C-reactive protein (CRP) — as a stronger early warning sign. Understanding CRP alongside cholesterol gives a clearer picture of cardiovascular risk and points to practical ways people can lower their chances of heart disease.

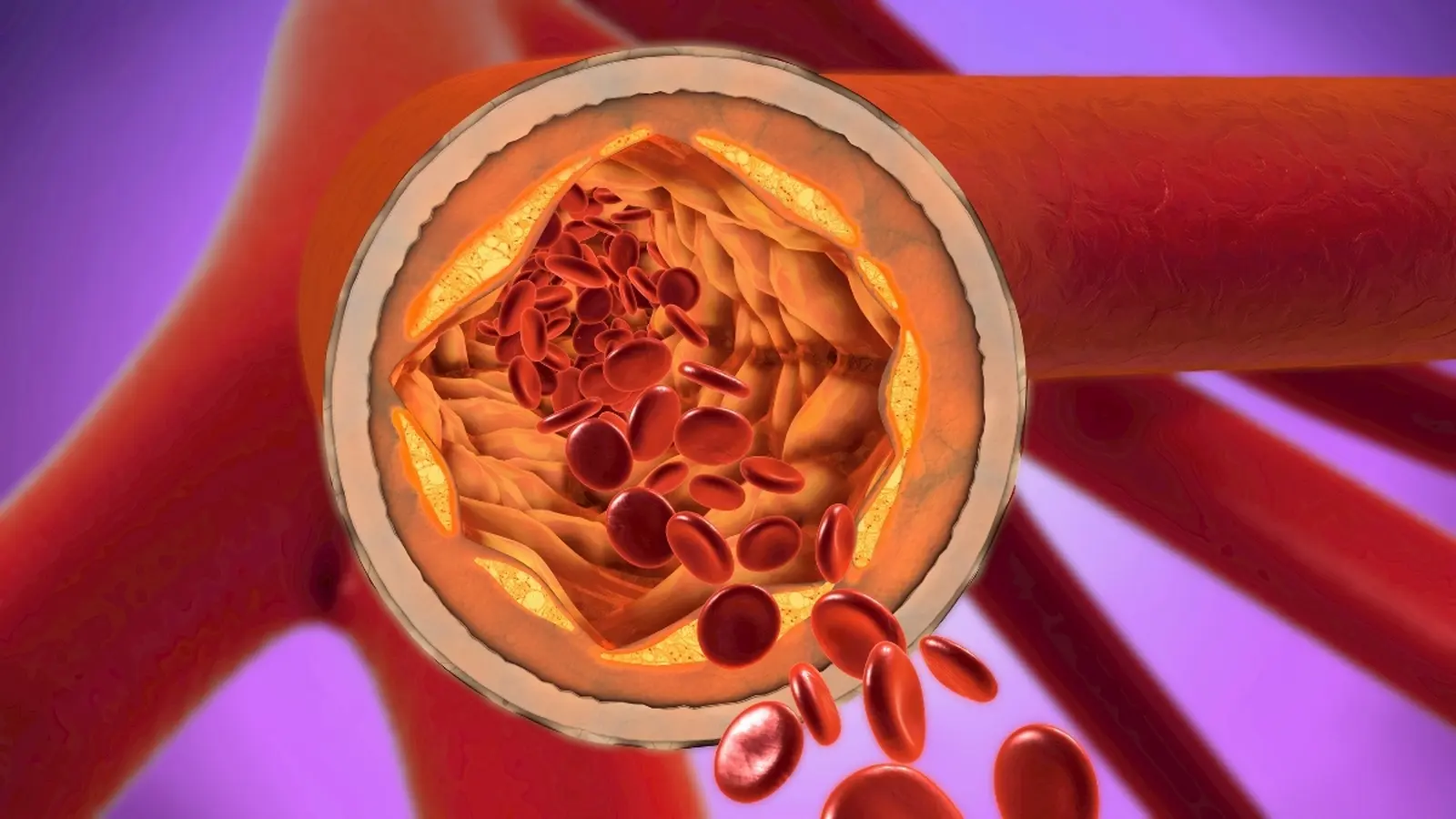

Fatty plaque buildup in the arteries causes a blockage that starves tissues of oxygen and can lead to a heart attack or stroke.

Inflammation: the missing piece in cardiovascular risk

Atherosclerosis is not just a story of cholesterol piling up in vessel walls. It’s an inflammatory process from beginning to end. When a blood vessel is damaged by high blood sugar, smoking, or other stresses, immune cells rush to the site and begin to engulf circulating cholesterol particles. Over years this immune activity builds the fatty plaques that narrow arteries.

CRP is a protein produced by the liver in response to immune activation. Clinically, cardiologists or primary care physicians use a high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) blood test to detect low-grade chronic inflammation that might otherwise be invisible. A level below 1 mg/dL generally indicates low cardiovascular inflammation and lower risk, while levels above 3 mg/dL are associated with increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Recent analyses show that CRP predicts heart events more reliably than LDL cholesterol alone, and in some studies performs comparably to blood pressure as a risk indicator.

How CRP testing changes the risk conversation

In September 2025 the American College of Cardiology recommended universal screening of CRP alongside cholesterol testing. The rationale is straightforward: measuring both inflammation and lipid status provides a richer, more actionable risk profile. Two people can have the same LDL cholesterol value but very different risks depending on their inflammatory state and the number of cholesterol particles in circulation.

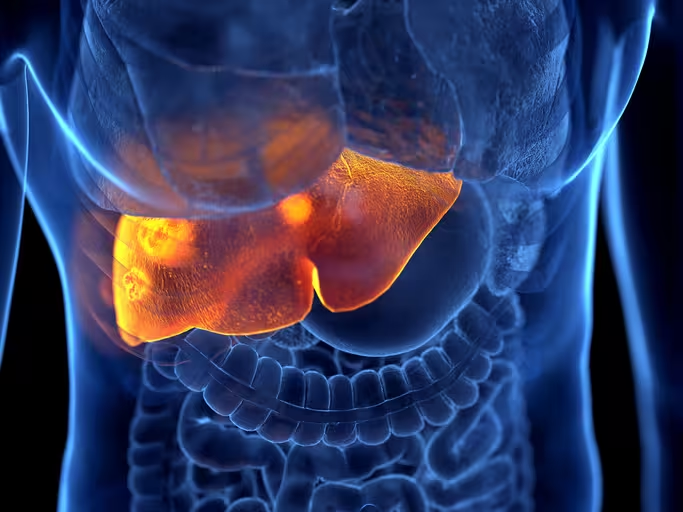

The liver produces C-reactive protein

Practical implications follow. A patient with moderately elevated LDL but low CRP may be managed differently than someone with similar LDL and high CRP. Likewise, discovering an elevated CRP can prompt clinicians to investigate and treat underlying drivers of inflammation — obesity, uncontrolled diabetes, chronic infection, poor oral hygiene, or autoimmune disease — rather than focusing narrowly on dietary cholesterol alone.

Beyond LDL: apolipoprotein B and lipoprotein(a) add clarity

Cholesterol levels still matter, but how they matter has nuance. LDL mass (the standard LDL-C measurement) is not the whole story. The number of LDL particles is a superior predictor of risk: more particles mean more opportunities for particles to penetrate damaged endothelium and fuel plaque growth. Apolipoprotein B (apoB) is a blood test that counts those particles and often outperforms LDL-C in predicting events.

Another important marker is lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). This molecule sits on the surface of LDL particles and makes them stickier, increasing the likelihood they will lodge in artery walls. Unlike CRP and apoB, Lp(a) is largely genetically determined and rarely changes with lifestyle; a single lifetime measurement can be informative.

Taken together — LDL-C, apoB, Lp(a), and hs-CRP — clinicians can assemble a more complete risk profile. This multimarker approach helps personalize prevention strategies and clarifies who might benefit most from medications like statins or newer anti-inflammatory therapies now being studied for cardiovascular protection.

How lifestyle alters CRP and particle numbers

The good news for patients is that many drivers of CRP and apoB are modifiable. Weight loss, regular physical activity, and smoking cessation reliably lower CRP. Diet matters: fiber-rich foods (beans, vegetables, whole grains), nuts and seeds, berries, olive oil, fatty fish (omega-3s), green tea, chia and flaxseeds are associated with reduced inflammation. Conversely, high added-sugar intake correlates with higher numbers of cholesterol particles and increased cardiovascular risk.

These lifestyle shifts work on multiple fronts: they can reduce chronic inflammation, lower the number of atherogenic particles, improve blood pressure and blood sugar — and together they shrink lifetime cardiovascular risk.

What this means for prevention and clinical care

Heart disease results from many interacting risk factors accumulated over a lifetime. Screening that pairs hs-CRP with traditional lipid panels and, when indicated, apoB and Lp(a), gives patients and clinicians a more complete map of that risk. That map can motivate targeted interventions: lifestyle changes, tighter control of diabetes or hypertension, dental care to address chronic oral inflammation, and pharmacologic therapy when appropriate.

Importantly, elevated CRP is not a single-disease sentence — it’s a signal that something in the body is chronically activating the immune system. Identifying and addressing that cause can reduce cardiovascular risk and often improves general health.

Expert Insight

"Measuring inflammation has been the missing lens in cardiovascular prevention for too long," says Dr. Elena Morales, a cardiometabolic specialist. "CRP gives us an early, inexpensive indicator that something systemic is contributing to atherosclerotic risk. When combined with apoB and Lp(a), we can move from generic advice to specific, evidence-based plans for patients."

Dr. Morales adds, "Screening is only valuable if it changes management — and in many cases it does. A raised CRP can strengthen the case for earlier lifestyle intervention or even medication in patients who otherwise fall into a gray area."

How to act on your numbers

- Ask your doctor for an hs-CRP test alongside routine cholesterol screening, especially if you have family history or other risk factors.

- Consider apoB and a one-time Lp(a) test if your risk is unclear or if early heart disease runs in your family.

- Prioritize weight management, consistent exercise, a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fiber, nuts and oily fish, and reduce added sugars and smoking.

- Address chronic conditions — diabetes, hypertension, dental infections — that drive inflammation.

By measuring both inflammation and lipids, patients and clinicians gain a clearer, more actionable view of cardiovascular risk. That clarity can change the conversation from chasing a single number to reducing the lifelong interactions that create heart disease.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

Had high hs-CRP despite normal cholesterol, lost 15 lbs and CRP dropped alot. Diet + daily walks actually helped, surprised me

bioNix

Wait so hs-CRP beats LDL alone? Sounds promising, but where's long term outcome data, and what about false positives? curious

Leave a Comment