3 Minutes

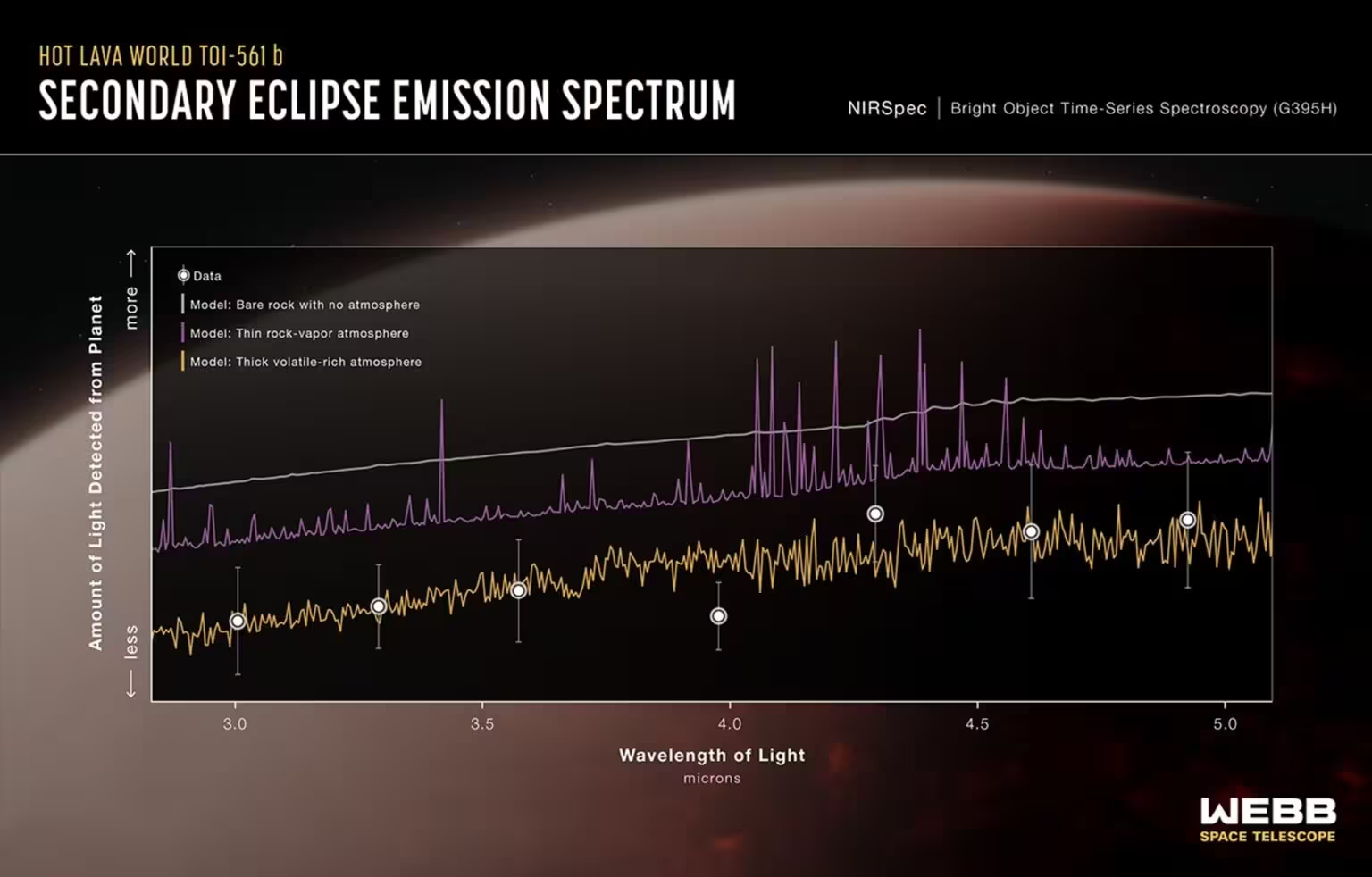

TOI-561 b is a scorching world by orbital standards — it hugs its star so closely that, without an atmosphere, its dayside temperature should soar to roughly 2,700°C (about 4,900°F). Yet thermal measurements tell a different story: the planet's dayside appears closer to 1,800°C. That mismatch hints at an unexpected, persistent atmosphere and a surprising interplay between surface and gas.

Why the dayside looks cooler than expected

When telescopes measure a planet's brightness in infrared light, they estimate a ‘‘brightness temperature’’ — the temperature a bare surface would need to emit that radiation. For TOI-561 b, observations register a brightness temperature far below the no-atmosphere prediction. Researchers suggest several atmospheric processes could explain the discrepancy.

Heat transport by winds

A thick envelope can drive strong winds that shift heat from the star-facing hemisphere to the nightside. That redistribution lowers the apparent dayside temperature when seen in infrared wavelengths.

Absorption by water vapor and other gases

Water vapor and other molecules efficiently absorb near-infrared radiation emitted from hot rock or magma. If present, these vapors can soak up outgoing light and re-radiate it at longer wavelengths, making the dayside look cooler to our instruments.

A long-lived atmosphere next to a magma ocean

One puzzle is how such a close-in planet could keep a substantial atmosphere for billions of years while being bombarded by stellar radiation that strips gases away. The leading idea links the atmosphere with a global magma ocean.

On the nightside, without atmospheric insulation, a magma ocean would freeze. But a dynamic balance may form: gases escape from the crust and magma into the atmosphere, some molecules leak into space, while the molten interior reabsorbs others. In effect, the magma ocean acts as both a source and a sink, buffering the planet's volatile inventory over geological time.

Iron, volatiles and atmospheric retention

Iron — abundant in rocky planets — might assist this exchange. Iron-rich magma can chemically trap oxygen and other volatile species, locking them in the interior or core and slowing net atmospheric loss. In this way, the same element that plays a role in Earth’s geology may help TOI-561 b hold onto an envelope of gas.

Implications for exoplanet studies

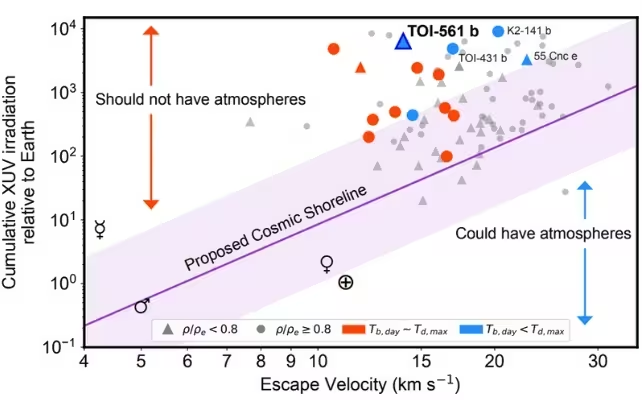

Comparative analyses of rocky exoplanets suggest a threshold: worlds with irradiation temperatures above roughly 2,000 K appear capable of replenishing volatile envelopes faster than they lose them. If TOI-561 b fits that pattern, its surprisingly cool dayside becomes a key case study for atmospheric survival under extreme irradiation.

Determining exactly why TOI-561 b retains a thick atmosphere will require more observations and refined theoretical models — especially spectroscopy that can detect specific molecules and missions that probe heat circulation on ultra-hot super-Earths. For now, the planet offers a vivid example of how surface magma and atmosphere can interact on worlds far hotter and stranger than our own.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment