6 Minutes

A simple flash of visible light can now write functioning electrodes directly onto skin and other surfaces — no toxic solvents, no specialist lasers. Researchers in Sweden have developed a water-based method that uses light to turn specially designed monomers into conductive polymers, opening new possibilities for wearable sensors, medical monitoring and safer manufacturing of organic electronics.

From liquid ink to working electrodes: how it works

At the core of the method are water-soluble monomers — the small chemical building blocks that, when linked together, form long conductive polymer chains. Instead of relying on strong, sometimes hazardous chemical initiators or ultraviolet light, the team triggers polymerization with ordinary visible light. The result: a conductive plastic that combines the electrical behavior of metals and semiconductors with the flexibility and softness of polymers.

In practice the process is straightforward. Researchers apply a liquid solution containing the monomers to a target surface — glass, textiles or even skin. Then they use a focused light source to trace the electrode pattern. Exposed regions polymerize and become conductive; unexposed solution can be washed away, leaving only the written circuit behind. The entire reaction occurs in water and avoids toxic additives, making the process intrinsically biocompatible.

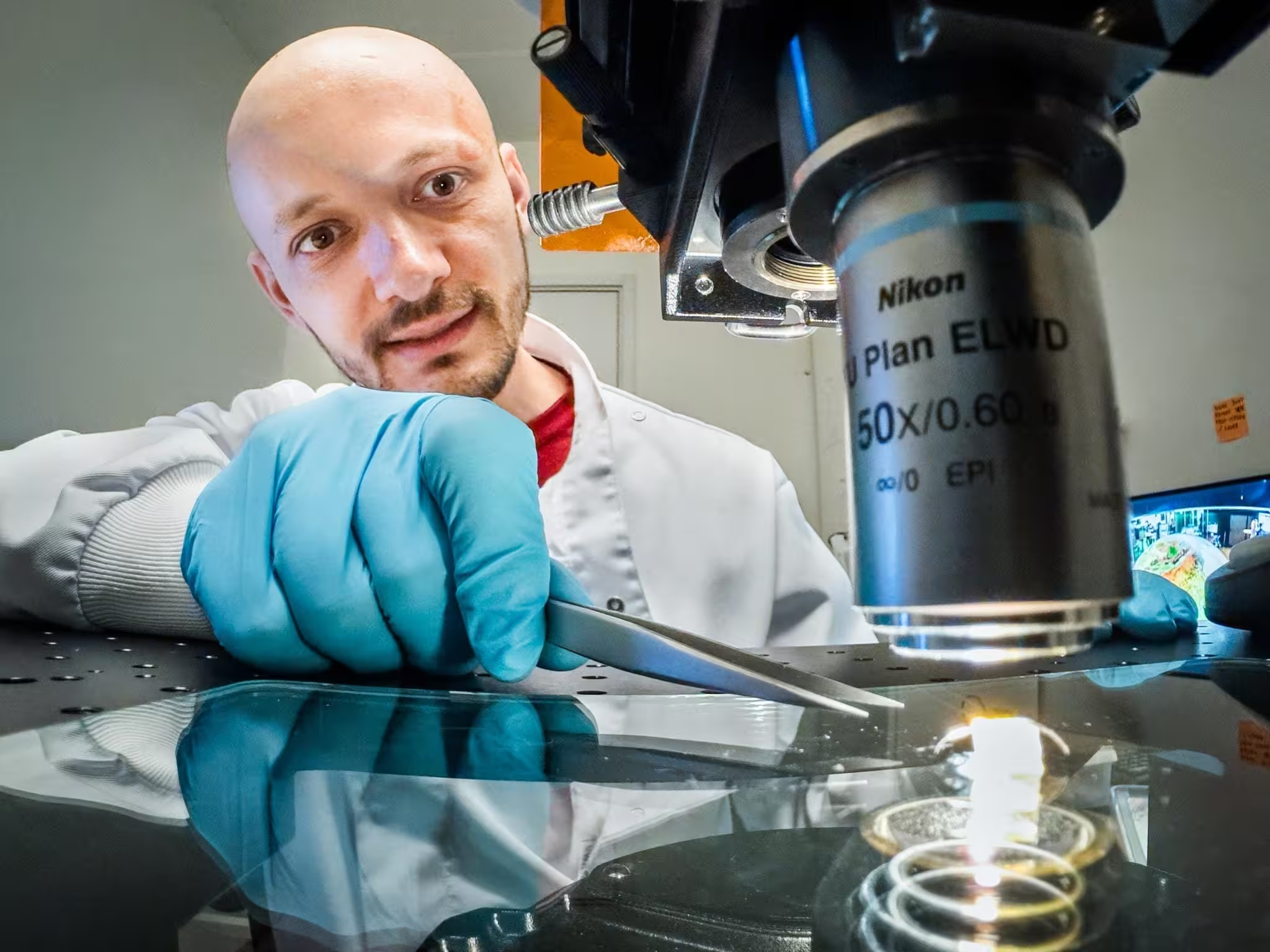

Xenofon Strakosas, assistant professor at the Laboratory of Organic Electronics, LOE, at Linköping University.

Why conductive polymers matter for medicine and wearables

Conductive polymers — also known as conjugated polymers — are attractive because they straddle the gap between rigid electronics and biological tissue. They can transport both electrons and ions, which helps them interface naturally with living systems. That soft, ion-conducting behavior is particularly valuable for biosensors, electrodes for neural recording, and wearable devices that must remain comfortable during prolonged contact with skin.

“I think this is something of a breakthrough. It’s another way of creating electronics that is simpler and doesn’t require any expensive equipment,” says Xenofon Strakosas of Linköping University’s Laboratory of Organic Electronics.

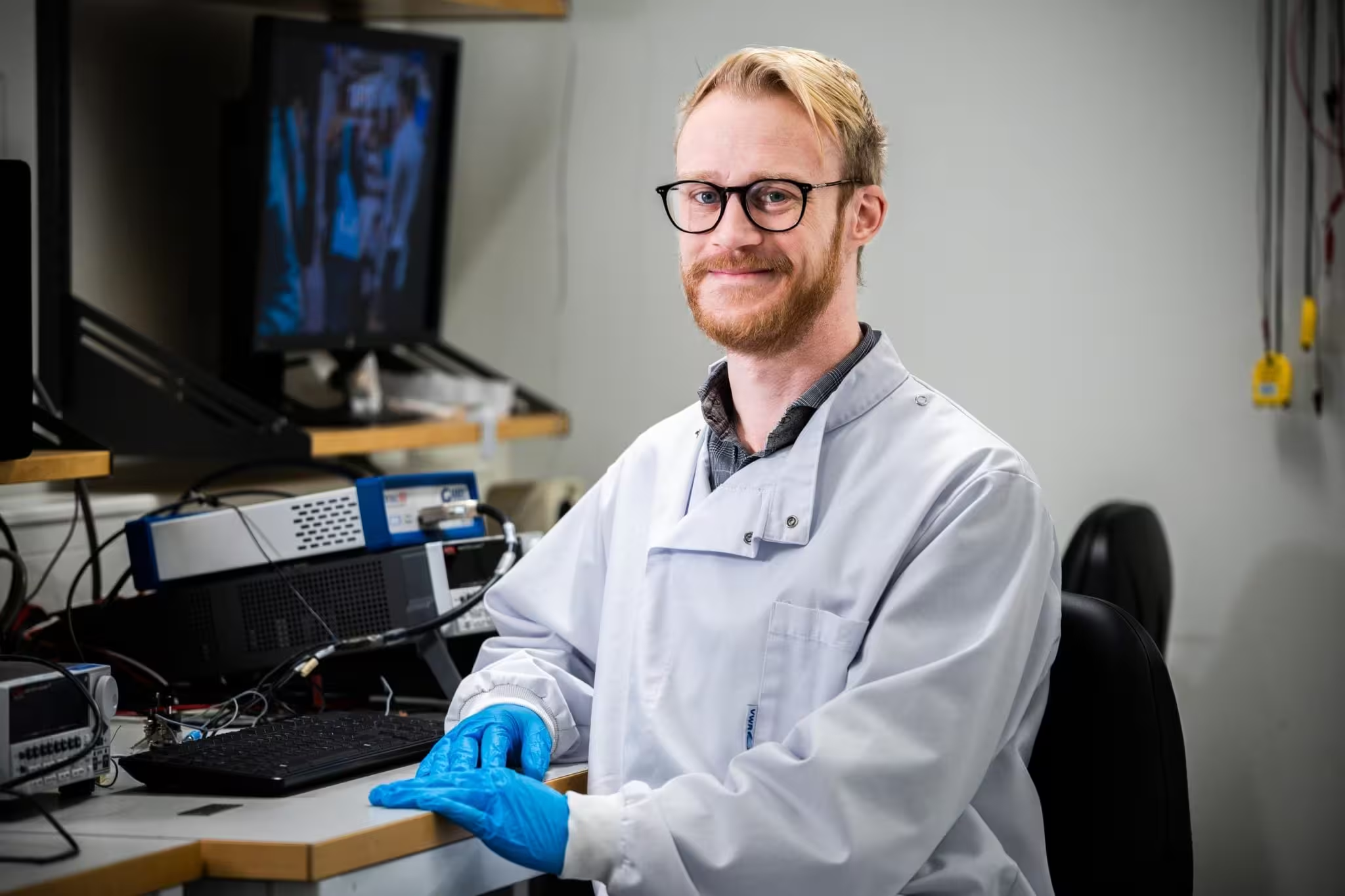

Tobias Abrahamsson, researcher at Linköping University

Real-world test: recording brain signals on skin

To demonstrate the method’s potential for medical monitoring, the team patterned electrodes directly onto the skin of anaesthetized mice and compared their signals with those recorded using conventional metal EEG electrodes. The printed conductive-polymer electrodes recorded low-frequency brain activity with greater clarity than traditional metal contacts, suggesting an improved signal interface between soft electronics and biological tissue.

According to Tobias Abrahamsson, the study’s lead author, the gentle chemistry of the polymer and its ability to carry ionic signals are crucial: "As the material can transport both electrons and ions, it can communicate with the body in a natural way, and its gentle chemistry ensures that tissue tolerates it — a combination that is crucial for medical applications."

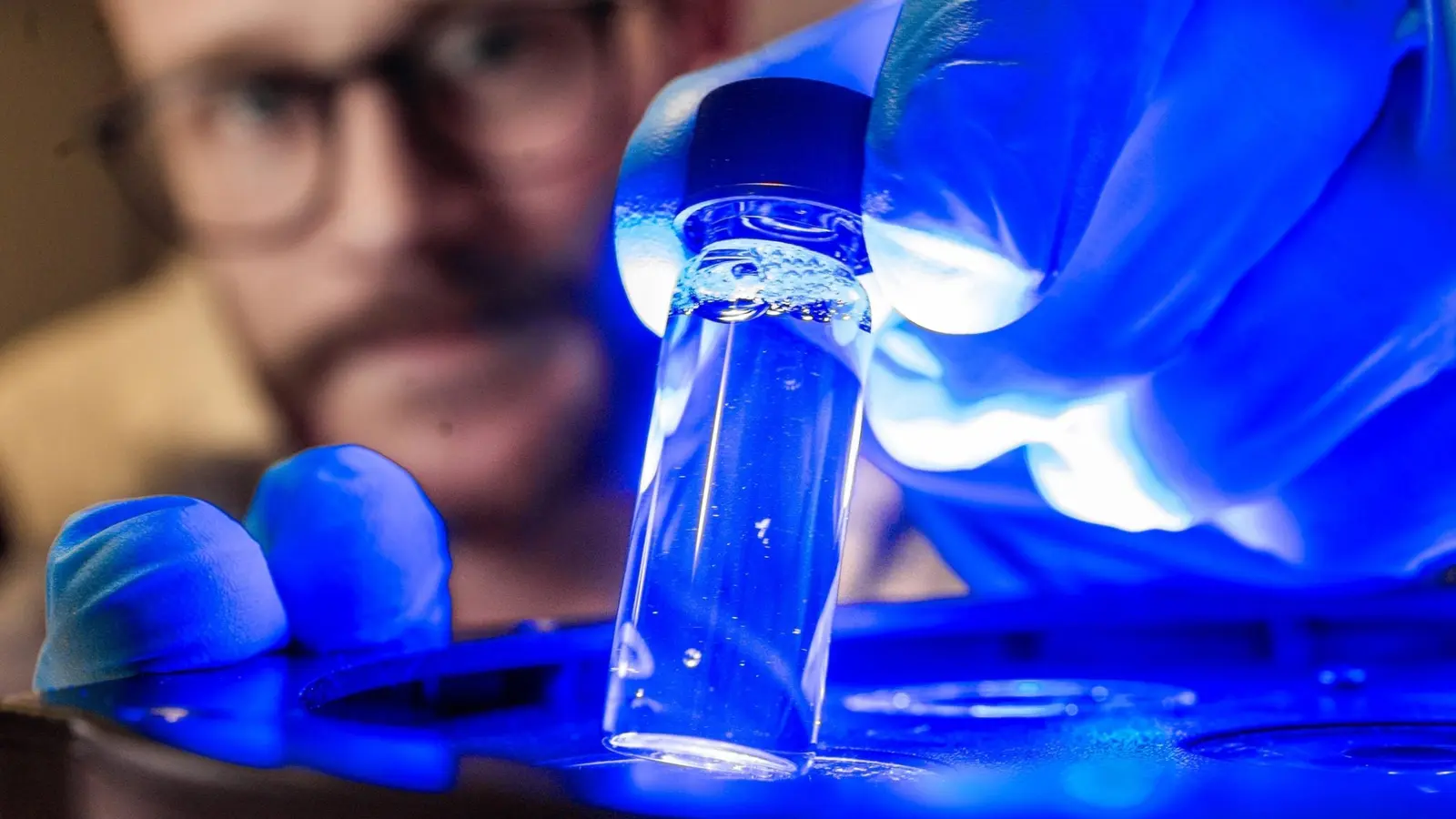

Visible light polymerization in water: The longer the monomer is exposed to light, the bluer and darker the solution becomes as it transforms into a conductive polymer material. Polymerization takes place directly in water, completely without toxic additives, making the process biocompatible. Credit: Thor Balkhed

Scaling up: textiles, mass production and safer fabrication

Because the approach works on diverse substrates, it can translate to a host of applications. Imagine sensors printed directly onto garments, disposable health patches produced without harmful solvents, or large-area organic electronic circuits manufactured with simpler tooling. The absence of dangerous chemicals and the use of visible light rather than UV or high-power lasers lower both safety risks and technical barriers for industry adoption.

The research team, a collaboration between Linköping University, Lund University and partners in New Jersey, emphasizes the flexibility of the technique. A modest LED lamp can trigger polymerization, meaning costly optical systems are unnecessary for many use cases. That accessibility could accelerate deployment in low-resource settings and bring new wearable health technologies to market faster.

What challenges remain?

Despite promising early results, several hurdles must be addressed before clinical or commercial roll-out. Long-term biocompatibility over days or weeks of continuous wear, adhesion and durability on moving skin, and standardization of electrical performance under sweat and motion are among the next questions researchers will tackle. Regulatory approval for medical devices adds another layer of testing and documentation.

Still, by removing toxic solvents and simplifying fabrication, visible-light-driven polymerization is poised to lower barriers and expand the kinds of organic electronics that can be made at scale.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Lin, a biomedical engineer focused on wearable neurotechnology, commented: “This approach is exciting because it combines material compatibility with a low-tech fabrication pathway. Soft, ion-conducting electrodes printed in situ could reduce impedance and improve comfort for long-term monitoring. The next step is to prove stability in real-world conditions — sweat, motion and repeated wear — but the concept is strong and practical.”

The study — published in Angewandte Chemie — presents a compelling proof of concept that visible light and carefully designed water-soluble monomers can produce biocompatible, flexible electrodes suitable for sensitive biological measurements. If subsequent work confirms durability and safety, this technique could reshape how we manufacture wearable medical electronics and organic circuits.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

blockDelta

Is this even true? Seems almost too easy, what's the catch, lifetime stability, skin reactions? also how pricey are the monomers

labSigma

Wow ok this is wild. Printing electrodes on skin with just water and visible light? If it's safe longterm, could change wearables big time. Curious about adhesion, sweat etc though

Leave a Comment