3 Minutes

A fossil jawbone unearthed in a cave on Hispaniola has preserved an unexpected record of insect behavior: multiple generations of solitary bees nested inside the tooth sockets of an extinct rodent. The discovery, described in Royal Society Open Science, shows how tiny animals can leave outsized traces of their lives—and how modern imaging can read those traces.

From owl prey to bee housing: the surprising chain of events

Paleontologists identify the jawbone as belonging to Plagiodontia araeum, a capybara-like rodent once native to the Caribbean. Researchers infer that an owl delivered the rodent remains into the cave after feeding, leaving the jawbone to be slowly buried in fine silt where its teeth loosened and fell out. The empty dental alveoli—natural cavities that previously held teeth—became real estate.

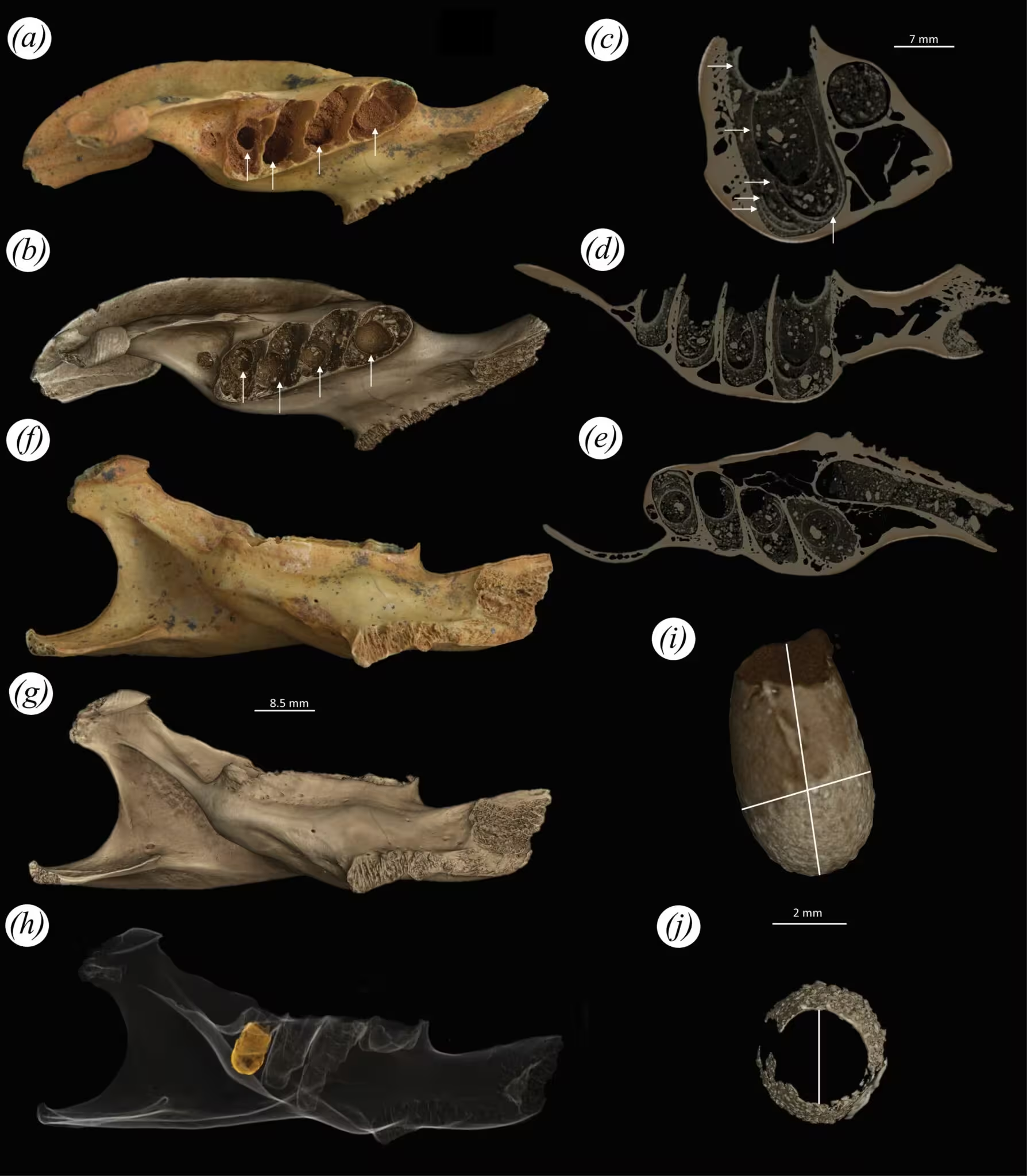

Rather than finding insect bodies, scientists found trace fossils: the carved, smoothed surfaces and packed cells within those alveoli that record nesting activity. The team named the ichnofossil Osnidum almontei for the burrowing bee traces preserved in the deposit.

How researchers decoded multi-generational nesting

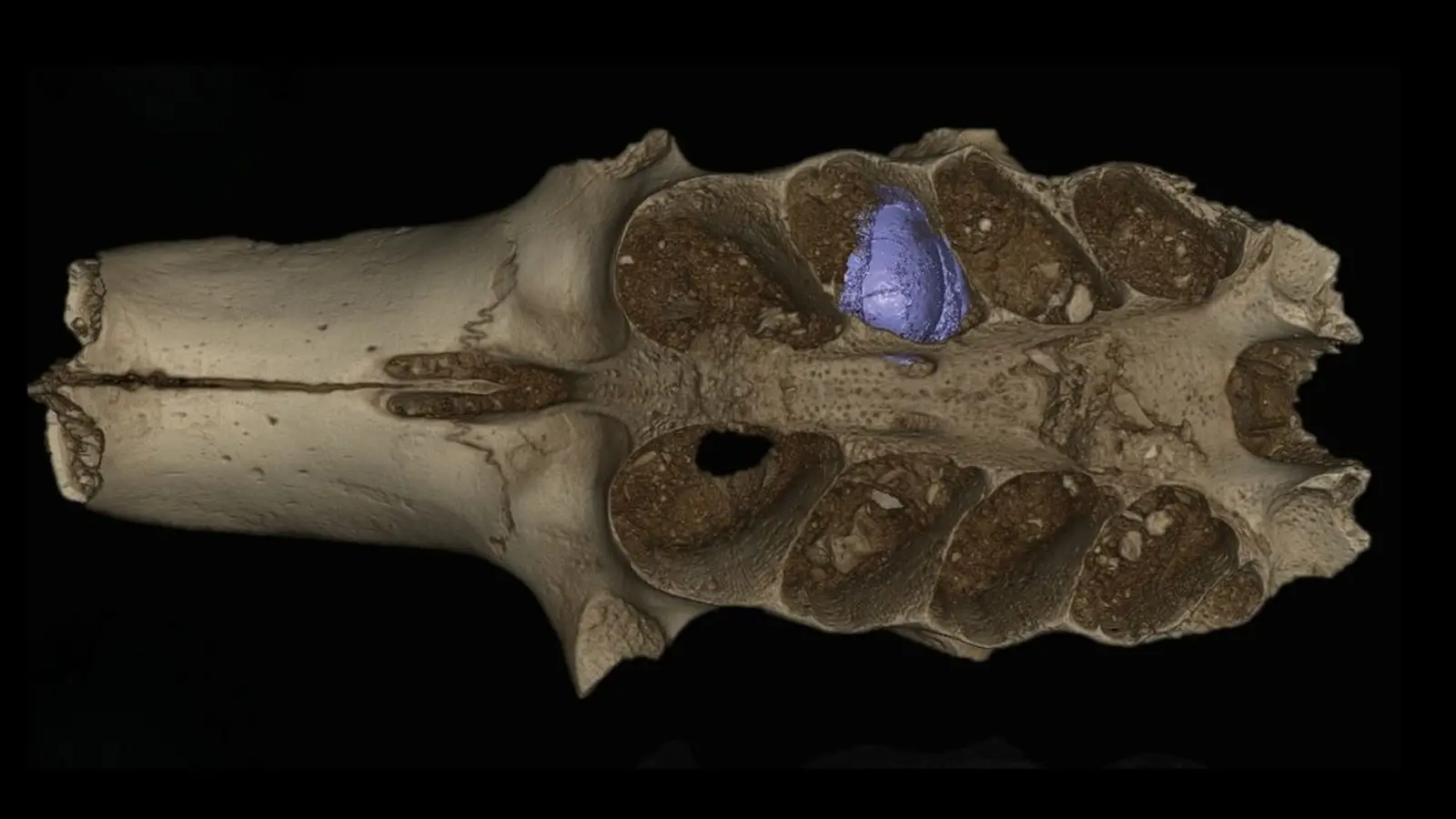

Lead paleontologist Lázaro Viñola Lopez and colleagues used micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) to examine the interior of bones without destroying them. The scans revealed repeated occupation of the same cavities across generations.

"Micro-computed tomography scans of the host bones show multi-generational use of the same cavity, suggesting repeated use and some degree of nest fidelity," Viñola Lopez and his colleagues explain in their published paper. "Fidelity in the nesting behaviour of bees is linked to the consistency or specificity with which a bee species or individual selects and uses particular nesting sites or materials."

Once aware of the pattern, the team recognized numerous similar cells in bones across the sediment matrix, including at least one within a sloth jawbone. The nests appear opportunistic—Osnidum almontei occupied any bony chamber available—and densely concentrated, indicating the cave served as a long-term nesting aggregation area for this solitary bee.

Why this matters to paleontology and ecology

These ichnofossils provide behavioral evidence rarely preserved in the fossil record. Instead of just cataloguing species, paleontologists can start to reconstruct interactions: predator-prey transport by owls, subsequent burial, and opportunistic nesting by bees. The finding expands our understanding of how ecosystems rearrange and reuse biological materials over time, and it highlights micro-CT as an essential tool for detecting subtle trace fossils.

CT scan and photograph images of left dentary of Plagiodontia araeum and type specimen of the ichnofossil, Osnidum almontei.

Beyond its novelty, the discovery raises questions about the diversity and behavior of extinct Caribbean insects and about preservation biases in paleontological deposits. Could other caves and bonebeds hide similarly informative ichnofossils? The study suggests paleontologists should start looking not just at bones for mammals, birds and reptiles, but for the small, repeated signatures left by insects that used those bones as homes.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment