5 Minutes

Imagine a chip where the material itself can store, process and adapt — not because of circuit design, but because of its chemistry. Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) have built molecular devices whose electronic behavior changes on demand, blurring the line between hardware and a living, learning system.

Researchers have created molecular devices that can change their electronic role on the fly, behaving like memory, logic, or even artificial synapses. By designing adaptable chemistry at the molecular level, they bring computing closer to how the brain actually works.

Why molecular electronics matters now

For decades the computing industry has relied on silicon transistors. But as devices shrink and energy costs rise, researchers are hunting for fundamentally different approaches. Molecular electronics promised a dramatic leap: build components from single molecules or thin molecular films and exploit chemistry to perform computation. In practice, though, molecules in a device don’t behave like isolated textbook parts — they interact, move ions, change oxidation states and produce nonlinear responses that are hard to predict or control.

At the same time, neuromorphic computing — hardware inspired by the brain — is searching for materials that can both compute and learn in the same physical substrate. Existing neuromorphic devices often emulate synapses through engineered switching in oxides or filaments, but these systems mimic learning rather than embed it naturally in the material response.

How IISc’s team merged chemistry with computation

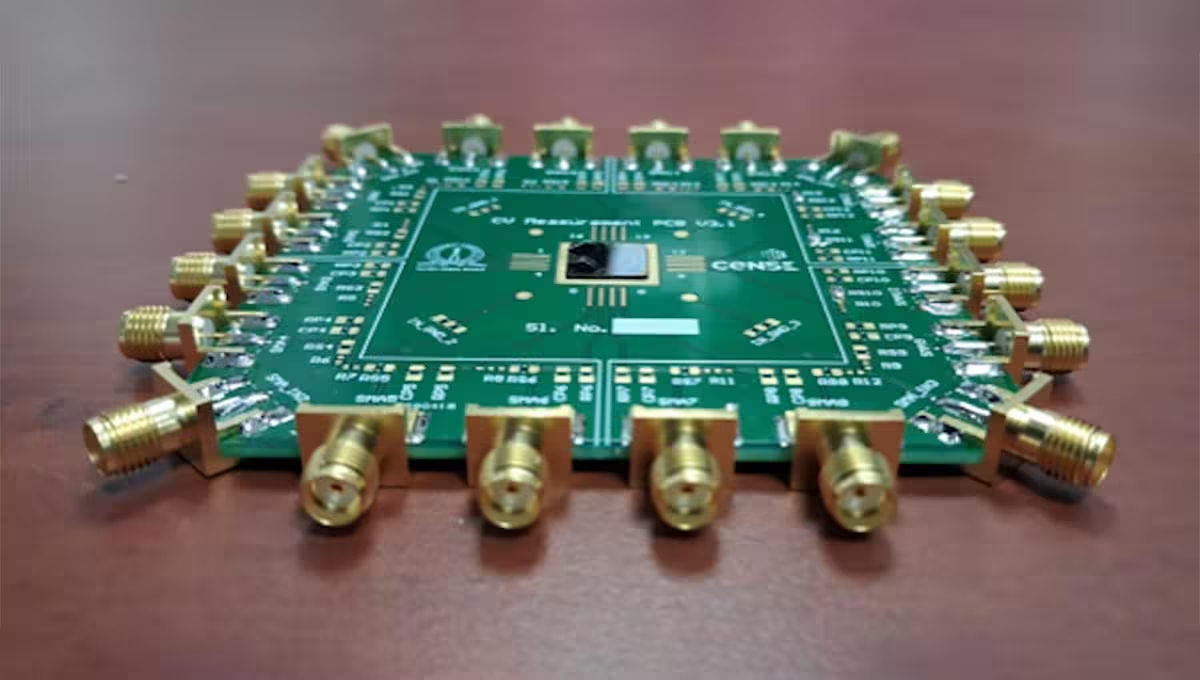

A multidisciplinary team at IISc led by Sreetosh Goswami set out to unify these two challenges. The result is a set of tiny molecular devices built from ruthenium complexes that can be tuned to perform radically different functions depending on how they are driven. With a single molecular architecture, the device can act as memory, a logic gate, a selector, an analog processor or an electronic synapse — including shifting between digital and analog behavior across broad conductance ranges.

That adaptability comes from chemical design. The team synthesized 17 ruthenium-based complexes and systematically varied ligands and the ionic environment. Small changes in molecular shape or nearby counterions altered how electrons transport through the film, how molecules oxidize and reduce, and how ions drift in the matrix. Those microscopic processes collectively determine switching times, relaxation behavior and the stability of each state.

From experiment to predictive theory

One of the study’s major advances is combining experiment with a rigorous theoretical framework. The researchers developed a transport model grounded in many-body physics and quantum chemistry that links a molecule’s structure to macroscopic device function. Instead of treating switching as an empirical quirk, the theory explains how correlated electron motion, ion dynamics and molecular redox events produce memory, logic and synapse-like plasticity.

That predictive capability is important: it means chemists can design molecular motifs to yield specific electrical responses rather than relying on trial-and-error. In practical terms, this turns chemistry into an architect of computation — a material-level route to devices that learn intrinsically.

What this could mean for neuromorphic AI hardware

By embedding storage, computation and adaptive learning inside the same material, these ruthenium complexes point toward neuromorphic hardware that is more compact and energy efficient than current transistor-based approaches. Instead of moving data between memory and processors, a single molecular layer could perform both roles, cutting latency and power use — a major advantage for AI at the edge and other low-energy applications.

The IISc team is already working to integrate these molecular films onto silicon platforms, aiming to build prototype hardware that blends the reliability of chips with the intrinsic intelligence of adaptive materials. If successful, such hybrid systems could accelerate next-generation AI accelerators and sensor nodes that learn from local data in real time.

Practical challenges and the road ahead

Important hurdles remain. Scalability, long-term stability, reproducible fabrication and compatibility with existing manufacturing workflows must all be demonstrated. The interplay of ions and electrons that gives these materials their capabilities can also cause drift or variability over long periods, so engineering for endurance will be critical.

Still, the study’s combination of chemical design, experimental validation and predictive theory provides a clear roadmap. Instead of treating chemistry as a supply chain for materials, the approach treats chemical structure as the design space for computation itself.

Expert Insight

“This work is a reminder that computation need not be confined to rigid circuits,” says Dr. Laura Chen, a neuromorphic hardware researcher at the Institute for Advanced Systems. “Embedding memory, logic and plasticity in a single material layer could radically reduce the energy and latency of AI systems. The key will be translating these promising molecular responses into reproducible, chip-compatible processes.”

Whether these shape-shifting molecular devices replace transistors is less important than the new paradigm they open: materials that compute by design. For researchers and engineers, the next steps are clear — integrate, scale and test these molecular layers in real-world AI tasks, and measure whether the chemistry-driven adaptability can deliver the efficiency and robustness modern applications demand.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

skyspin

is this even true? molecules as synapses sounds cool but repeatability, temps, long term drift, fab steps??

labcore

wow, chemistry as hardware? mind blown. if they can scale this, edge AI could be tiny and hungry for power no more… but durability tho

Leave a Comment