6 Minutes

New biomechanical modeling suggests that a Triassic-era cynodont, Thrinaxodon liorhinus, could hear airborne sounds using an early eardrum about 250 million years ago. That timing pushes the origin of sensitive mammal-like hearing back by roughly 50 million years and reshapes our understanding of how early mammal ancestors sensed their world.

Why hearing matters in mammal evolution

The evolution of the mammalian middle ear — a system including an eardrum plus tiny ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes) — enabled detection of a wide range of airborne sounds and finer acoustic detail than bone conduction alone. For early mammal relatives, many of which were likely nocturnal, improved hearing would have offered major advantages for finding prey, avoiding predators, and navigating in low light.

Paleontologists long debated when airborne hearing first appeared in the lineage that led to modern mammals. Traditional reconstructions placed the full shift to a detached middle ear and functional eardrum well after the Triassic. The new study upends that timeline by combining fossil anatomy with engineering-grade simulations.

Turning a fossil into an engineering model

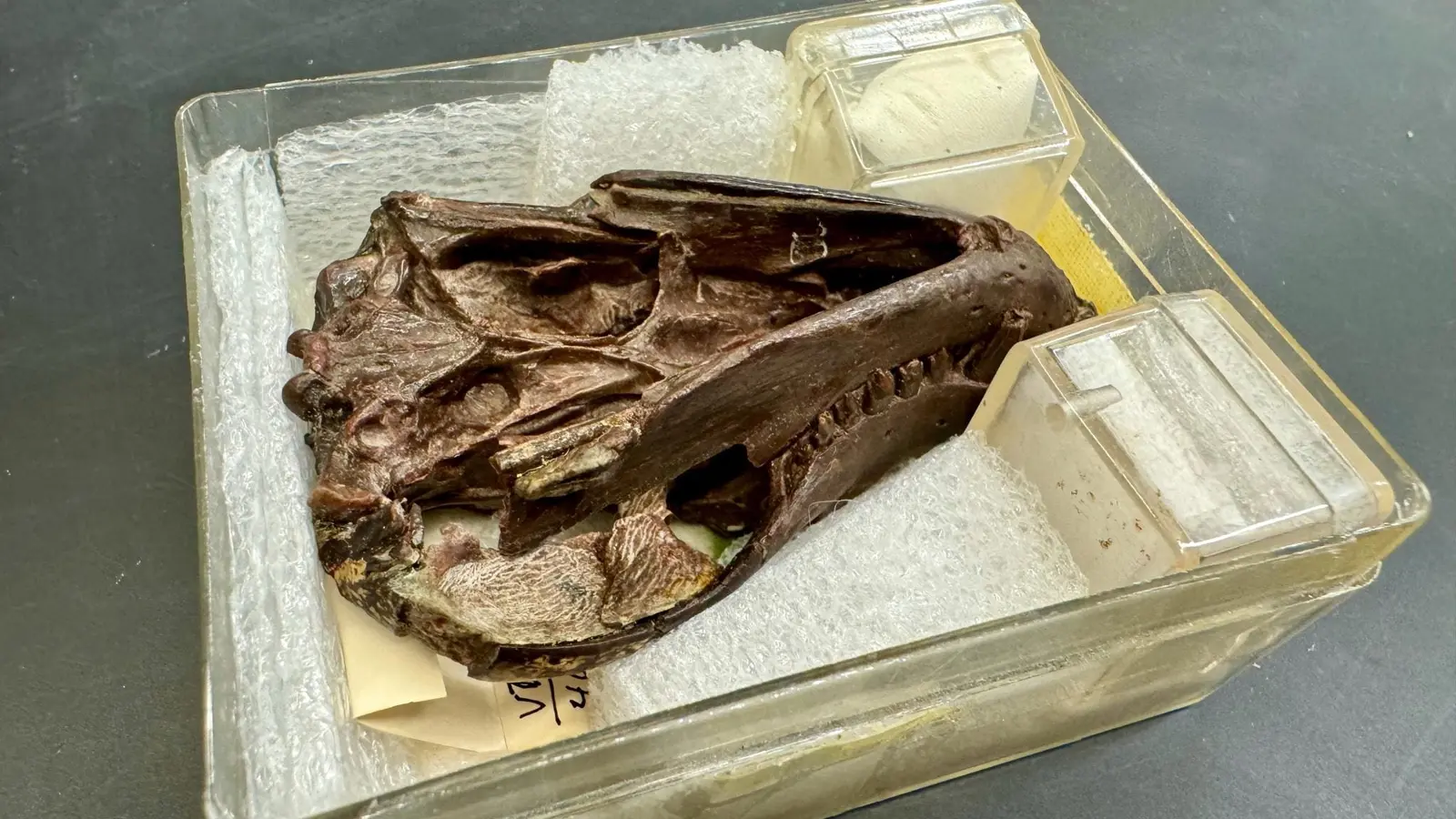

Researchers at the University of Chicago used high-resolution CT scans of a well-preserved Thrinaxodon skull and jaw housed at the University of California Berkeley Museum of Paleontology. The scans produced a detailed 3D reconstruction of the bones, curves and cavities, providing the geometric foundation for physical simulation.

Next, the team applied finite element analysis (FEA) using Strand7 software — a computational method widely used in engineering to predict how structures respond to forces and vibrations. By assigning realistic material properties drawn from living mammals (bone density, ligament stiffness, soft-tissue thickness), the model could estimate how sound pressures of different frequencies would make parts of the jaw and a hypothesized membrane vibrate.

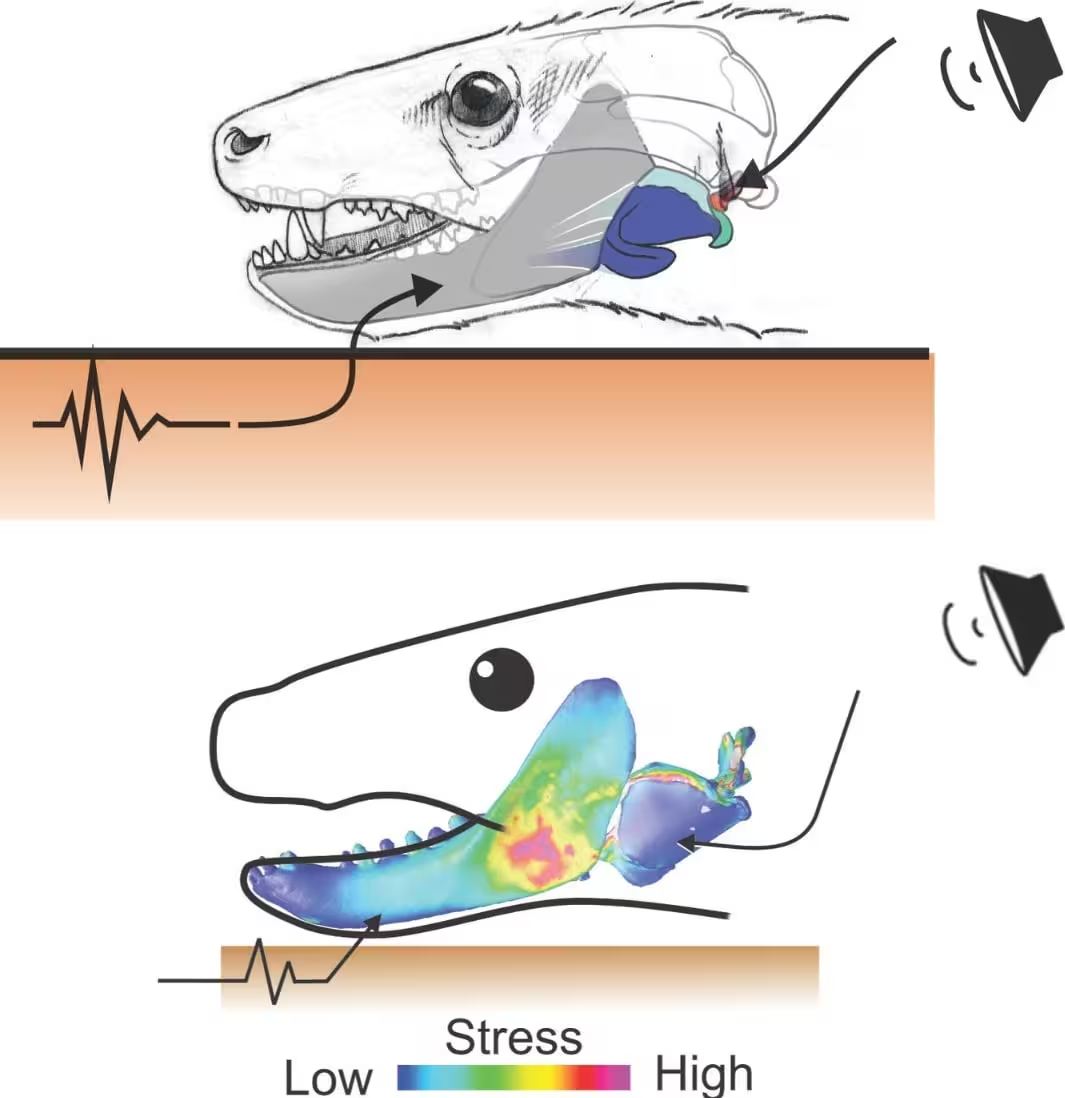

Simulations showed that sound waves applied to the eardrum of Thrinaxodon (top) would have enabled it to hear much more effectively than through bone conduction alone (bottom).

Evidence that an eardrum was already doing the heavy lifting

The simulations returned a clear result: a membrane positioned in a natural recess along Thrinaxodon’s lower jaw would have transmitted airborne sound efficiently to the chain of ear bones, producing vibrational amplitudes sufficient to stimulate auditory nerve endings. While some degree of jaw-based, bone-conducted hearing likely persisted, the modeled eardrum accounted for most of the animal’s effective hearing across relevant frequency ranges.

Historically, many scientists assumed these early cynodonts relied mainly on bone conduction or "jaw listening," where vibrations travel through bone to the inner ear. About 50 years ago, Edgar Allin proposed that a membrane stretched across a curved section of the jaw could function as an early tympanic membrane. Until now, biomechanics to test that idea were limited; modern CT imaging plus FEA allowed direct, quantitative testing of Allin’s suggestion.

3D models of the jaw and associated middle ear bones of the Triassic mammal ancestor Thrinaxodon show that the switch to mammal-like hearing with an eardrum evolved much earlier than previously thought.

What the findings mean for paleontology and sensory evolution

Placing airborne hearing this early implies that several mammal-like soft-tissue and behavioral traits may have emerged sooner than assumed. If Thrinaxodon and close relatives possessed a working eardrum and a functional ossicle chain connected to that membrane, then natural selection could have refined auditory sensitivity and frequency discrimination in deep time while these animals coexisted with early archosaurs and other reptilian lineages.

Practically, the study demonstrates how modern computational tools allow paleontologists to turn morphological questions into testable engineering problems. By integrating fossil geometry with empirically grounded material parameters, researchers can move beyond conjecture to quantitative assessments of sensory function in extinct organisms.

Zhe-Xi Luo (left) holds the fossil specimen of Thrinaxodon, while Alec Wilken (right) holds a 3D printed model of the inner ear of a modern opossum for comparison.

Testing old hypotheses with new tools

Alec Wilken, the graduate student who led the project, and his advisors Zhe-Xi Luo and Callum Ross translated a classic paleontological question into a computational experiment. By combining CT-derived geometry, comparative tissue-property data, and FEA, they demonstrated that the jaw recess could support a tympanic membrane capable of airborne hearing. In short, the eardrum idea that intrigued researchers for decades is supported when examined with modern biomechanical methods.

The implications extend beyond Thrinaxodon: if similar jaw geometries and soft-tissue reconstructions are validated in related cynodonts, the origin of mammal-like hearing may have been a gradual process with functional stages already present in the Early Triassic.

Expert Insight

Dr. Helena Márquez, a comparative auditory biologist (fictional), commented: "This research is a great example of interdisciplinary science. Fossils give us shape, engineering gives us function. The finding that an eardrum could operate effectively in a jaw-linked system changes how we read the fossil record for sensory evolution. It suggests acoustic adaptations were part of these animals' toolkit far earlier than we thought."

She added, "Careful work remains to confirm how widespread this design was across cynodonts, but the method is powerful: it lets us ask not just what bones looked like, but how extinct animals actually experienced their environments."

Broader technologies and future directions

The study highlights several modern tools reshaping paleontology: micro-CT scanning for non-destructive internal imaging, 3D printing for physical comparisons, and finite element modeling for biomechanical inference. Future work may expand simulations to include soft-tissue variability, different environmental soundscapes, and comparisons across multiple cynodont taxa to map the pace and sequence of auditory innovations.

Additionally, combining biomechanical models with fossil sites that preserve delicate anatomy could identify other sensory adaptations — for example, olfactory or visual changes — that co-evolved with early mammalian hearing.

By bringing engineering rigor to evolutionary questions, the research team has opened a new pathway to test long-standing hypotheses about the sensory lives of long-extinct species.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

pumpzone

Is this even true? Simulations are cool but assumptions about soft tissue, ligament stiffness etc could sway the outcome. Need more fossils, not just one

bioNix

Wait, hearing 250M yrs ago? mind blown. The CT+FEA combo is clever, but I wanna see results across more cynodonts, still, wow

Leave a Comment