8 Minutes

Discovery summary: a hidden receptor that controls bone strength

Researchers at Leipzig University have identified a previously underappreciated receptor — GPR133 — that acts as a molecular "bone switch" controlling skeletal strength. In laboratory studies using mice, activating GPR133 with a novel small molecule called AP503 increased bone density and reversed changes that resemble osteoporosis. The work points to a new biological target for therapies that could both preserve and rebuild bone, addressing a major unmet need as populations age.

Why new osteoporosis treatments are urgently needed

Osteoporosis is a chronic condition characterized by progressive loss of bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration, which increases fracture risk. In Germany alone, roughly six million people are affected, most of them women, particularly after menopause. Current treatments — such as bisphosphonates, denosumab, or anabolic agents like teriparatide and romosozumab — can reduce fracture risk but have limitations, including side effects, limited duration of use, and incomplete restoration of bone quality. There is a pressing demand for safer, long-term strategies that both prevent bone loss and restore skeletal integrity.

To find alternatives with better safety and efficacy profiles, scientists are exploring novel molecular targets in bone biology. One promising target is GPR133, an adhesion G protein-coupled receptor (adhesion GPCR) that until recently has been little studied in the context of bone remodeling.

Mechanism: How GPR133 activation remodels bone

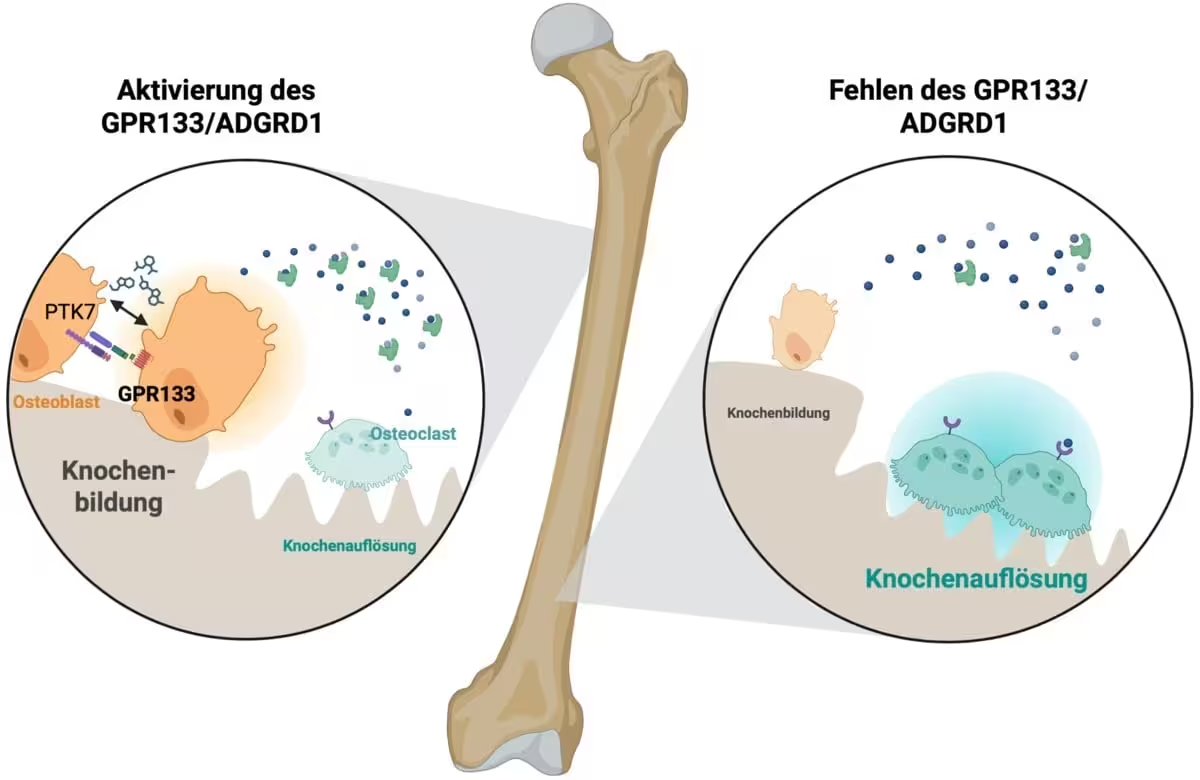

GPR133 belongs to a class of membrane proteins called adhesion G protein-coupled receptors. These molecules are activated by mechanical cues and cell–cell contacts and transduce signals inside the cell via G proteins. In bone tissue, activation of GPR133 triggers a cascade that increases activity of osteoblasts — the cells that form new bone — while simultaneously dampening the activity of osteoclasts — the cells responsible for bone resorption. By shifting the balance toward bone formation, GPR133 signaling strengthens bone structure and enhances durability.

When GPR133 is activated in bone tissue, it triggers a signal that stimulates bone-forming cells (osteoblasts) and inhibits bone-resorbing cells (osteoclasts). Credit: Biorender, Ines Liebscher

Laboratory experiments at the Rudolf Schönheimer Institute of Biochemistry showed that genetic impairment of GPR133 in mice causes early-onset reductions in bone density, a phenotype that mirrors aspects of human osteoporosis. Conversely, pharmacological stimulation of the receptor using AP503 — identified through computational screening — produced substantial gains in bone mass and improved mechanical properties of the skeleton in both healthy and osteoporotic animal models.

Activation modes: mechanical strain and cell interactions

GPR133 is responsive to mechanical strain and to signals arising from direct interactions among bone cells. This dual sensitivity suggests the receptor functions as a physiological integrator of both physical load (exercise, weight-bearing) and local intercellular signaling, translating those cues into anabolic (bone-building) responses.

Study findings and experimental details

In the Leipzig study, investigators used a combination of molecular genetics, cell biology, and in vivo pharmacology. Key findings include:

- Mice with reduced function of GPR133 developed low bone mass at young ages, indicating the receptor is required for normal bone accrual and maintenance.

- AP503, a small-molecule agonist discovered by high-throughput computational screening, selectively stimulated GPR133 and reproduced its natural anabolic signalling in bone.

- Treatment with AP503 increased bone mineral density, improved microarchitecture, and reversed osteoporosis-like changes in treated mice.

These preclinical results support the concept that targeting GPR133 could both prevent age-related bone loss and actively rebuild bone that has already been lost. Notably, previous work by the same group showed AP503 also strengthens skeletal muscle, raising the possibility of coordinated benefits for musculoskeletal health — a desirable feature for interventions aimed at frail, older adults.

Clinical implications and development challenges

The identification of GPR133 and AP503 opens a translational pathway but also presents typical challenges:

- Safety and specificity: AP503’s selectivity for GPR133 and off-target profile must be thoroughly characterized. Long-term modulation of GPCR signaling requires careful toxicology studies.

- Pharmacokinetics and delivery: Chemical optimization may be needed to ensure oral bioavailability, metabolic stability, and suitable dosing for humans.

- Efficacy in larger mammals and humans: Mouse models are informative but do not fully capture human bone remodeling dynamics. Larger-animal studies and ultimately phased clinical trials will be required to evaluate fracture risk reduction and functional outcomes.

Because current standard-of-care drugs already reduce fracture risk, any new therapy must demonstrate either superior efficacy, better safety for long-term use, or unique benefits such as simultaneous muscle strengthening. The potential to both prevent bone loss and regenerate bone makes GPR133 a highly attractive target for pharmaceutical development.

Background and research context: a decade of GPCR study in Leipzig

Leipzig University has invested more than a decade into the structural and functional study of adhesion GPCRs through Collaborative Research Centre 1423, "Structural Dynamics of GPCR Activation and Signaling." This long-term, focused effort has made the university an international center for adhesion GPCR research and enabled the multidisciplinary approaches that uncovered GPR133’s role in bone biology.

"If this receptor is impaired by genetic changes, mice show signs of loss of bone density at an early age – similar to osteoporosis in humans. Using the substance AP503, which was only recently identified via a computer-assisted screen as a stimulator of GPR133, we were able to significantly increase bone strength in both healthy and osteoporotic mice," explains Professor Ines Liebscher, lead investigator of the study from the Rudolf Schönheimer Institute of Biochemistry at the Faculty of Medicine.

Expert Insight

Dr. Martin Keller, fictitious translational pharmacologist and senior R&D advisor with experience in musculoskeletal drug development, comments: "Targeting adhesion GPCRs such as GPR133 is a smart strategy because these receptors lie at the interface between mechanical stimuli and cellular response. A compound that can safely emulate exercise-induced signalling and tilt remodeling toward bone formation could transform long-term treatment for osteoporosis — especially for patients who cannot tolerate current therapies. The path from mouse to market is long, but the dual muscle-and-bone benefit reported here is particularly compelling for geriatric care."

Next steps and future prospects

The Leipzig team is pursuing several follow-up projects to define AP503’s mechanism in more detail and to test the receptor’s role in other disease models. Important next steps include:

- Dose-response and chronic administration studies to evaluate sustained effects and safety.

- Structural studies to understand how AP503 binds and activates GPR133, facilitating rational optimization of drug-like properties.

- Studies in larger animal models to better predict human pharmacology.

- Early-stage clinical development, if preclinical safety and efficacy are confirmed.

If these paths advance successfully, GPR133 agonists could join the next generation of osteoporosis therapies, particularly for postmenopausal women and older adults at high risk of fragility fractures.

Conclusion

The discovery of GPR133 as a regulator of bone strength and the demonstration that a small-molecule activator, AP503, can increase bone density and reverse osteoporosis-like changes in mice represent a promising advance in bone biology. Building on a decade of adhesion GPCR research at Leipzig University, this work provides both a fresh therapeutic target and a conceptual framework for interventions that integrate mechanical and cellular signals to rebuild and preserve skeletal health. While translation to human treatments will require extensive follow-up, the combined potential to strengthen bone and muscle positions GPR133 modulation as a high-priority avenue for addressing age-related musculoskeletal decline.

Scientists found a “bone switch” that could stop osteoporosis and keep bones strong with age. Credit: Shutterstock

When GPR133 is activated in bone tissue, it triggers a signal that stimulates bone-forming cells (osteoblasts) and inhibits bone-resorbing cells (osteoclasts). Credit: Biorender, Ines Liebscher

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment