10 Minutes

Why the Sun’s Poles Matter

The polar regions of the Sun remain among the least observed yet most influential areas in solar physics. Observations from Earth and from spacecraft in the ecliptic plane give detailed views of sunspots, active regions, flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs), but they provide only a side-on perspective. The result is an incomplete picture of the global solar magnetic field and of the sources that feed the fast solar wind and shape space weather across the heliosphere.

Understanding the poles is essential because polar magnetic fields set the large-scale dipole of the Sun, influence how and when magnetic polarity reversals occur, and are linked to the streams of high-speed solar wind that dominate much of interplanetary space. A new mission designed to achieve a high-inclination solar orbit promises to provide the first sustained, high-resolution view of these regions and help answer three enduring scientific questions about our star.

Scientific Background: The Solar Dynamo and Magnetic Cycle

The Sun’s magnetic activity waxes and wanes on roughly an 11-year timescale, marked most visibly by the rise and fall in sunspot counts. Beneath these surface changes lies the solar dynamo — a process that converts plasma flows and rotation into magnetic field. Two ingredients are central to dynamo models: differential rotation (the fact that the Sun’s equator rotates faster than its poles) and meridional circulation (poleward surface flows and equatorward return flows deeper in the convection zone) that transport magnetic flux.

Despite decades of helioseismology and modeling, the details of deep flows remain debated. Some helioseismic inversions suggest poleward flows at depths where classical flux-transport dynamos expect equatorward return flows, creating tension with traditional models. High-latitude magnetic mapping and measurements of plasma motions near the poles are therefore critical to test and refine dynamo theory. Direct polar observations can reveal how polar field buildup seeds the next sunspot cycle and why the amplitude and timing of cycles vary.

Fast Solar Wind: Origins and Acceleration Mechanisms

One of the foundational insights from the Ulysses mission (launched in 1990) was that the fast solar wind largely emanates from extensive coronal holes at high latitudes. These coronal holes are regions of open magnetic field lines that let charged particles escape into the heliosphere at supersonic speeds. Yet important questions remain: do high-speed streams emerge from dense plumes within coronal holes or from the more diffuse inter-plume plasma? What role do wave-driven processes (for example, Alfvén waves), small-scale magnetic reconnection events, or hybrid mechanisms play in accelerating and heating the wind?

Resolving these questions requires two complementary measurements: high-resolution remote sensing of the polar corona and in-situ sampling of the solar wind above the poles. Imaging in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) and X-rays can identify structures and heating events in the low corona, while in-situ instruments measure particle distributions, composition, and magnetic fields to link remote features to the actual plasma streams flowing into interplanetary space.

Space Weather Propagation and Global Context

Space weather describes how solar activity — flares, CMEs, and variable solar wind — perturbs the heliospheric environment. Extreme events can disrupt satellite operations, high-frequency radio, GNSS navigation, airline communications at high latitudes, and even terrestrial power grids. Predicting space weather reliably requires a global, three-dimensional view of how magnetic structures evolve and propagate.

From an ecliptic-bound vantage point, the projection and propagation of CMEs are difficult to disentangle. Observations from high solar latitudes provide an overhead perspective of the ecliptic plane, enabling clearer tracking of CME geometry and more accurate determination of propagation directions and expansion. Such global coverage improves models of CME impact timing and helps operational forecasting centers mitigate threats to technology and human spaceflight.

Past Efforts and the Need for a Polar Perspective

The importance of polar observations is not new. Ulysses provided the first in-situ measurements of the polar solar wind and showed how fast streams vary with solar cycle phase, but it lacked remote-sensing imagers to link wind sources to coronal structures. More recent missions, such as ESA’s Solar Orbiter, are gradually increasing their orbital inclination; Solar Orbiter will reach mid-high latitudes (around 34° and higher over time), offering unprecedented but still limited polar views.

Multiple mission concepts have been proposed to access the poles more directly: Solar Polar Imager (SPI), POLARIS, SPORT, Solaris, and the High Inclination Solar Mission (HISM). Proposed strategies include advanced propulsion such as solar sails or leveraging multiple gravity assists to tilt spacecraft orbits progressively. Each concept emphasized combining remote-sensing cameras and spectrometers with in-situ particle and field instruments to connect coronal physics with heliospheric consequences.

The Solar Polar-orbit Observatory (SPO): Mission Overview

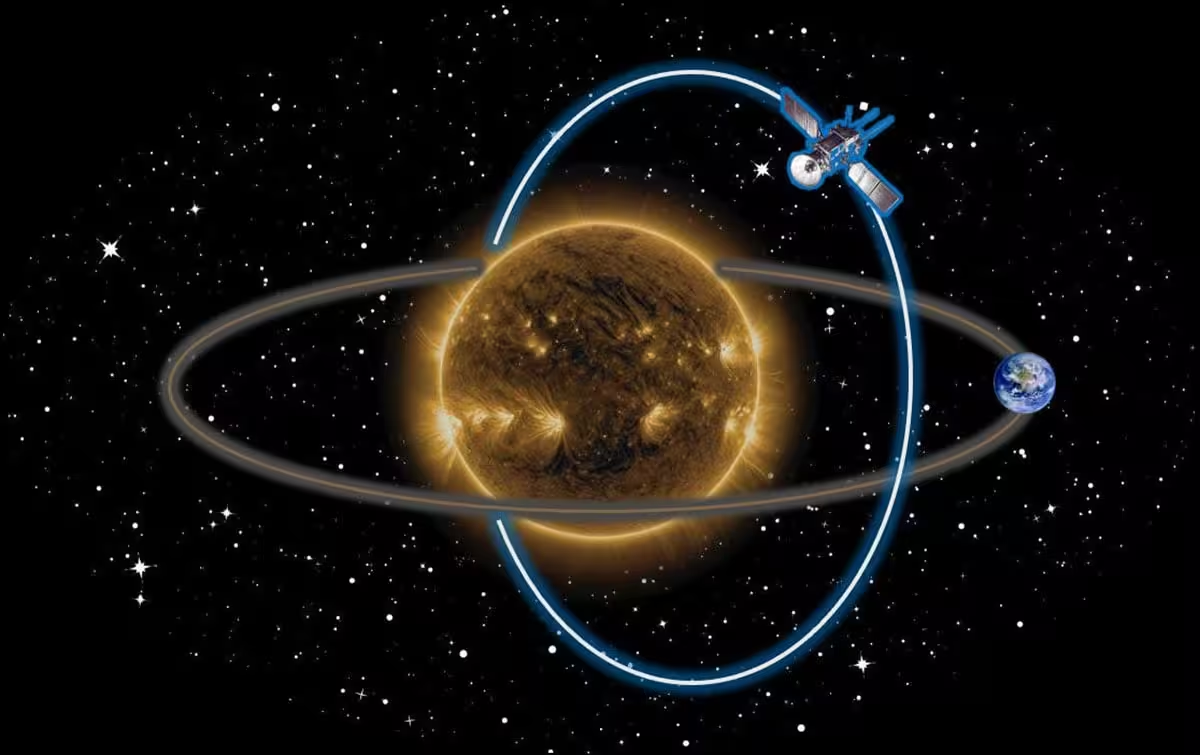

The Solar Polar-orbit Observatory (SPO) is a mission designed specifically to obtain sustained, high-latitude observations of the Sun. Planned for launch in January 2029, SPO will use a Jupiter gravity assist (JGA) following several Earth flybys to reorient its orbital plane out of the ecliptic. The nominal scientific orbit targets inclinations up to 75° with a 1.5-year orbital period and a perihelion near 1 AU. In an extended phase, SPO could climb to about 80°, delivering the most direct and prolonged polar viewing geometry achieved to date.

SPO’s planned operational lifetime is roughly 15 years, including an 8-year extended mission window. That duration is deliberately chosen to span a solar minimum and at least one solar maximum — crucially including the projected polarity reversal around the mid-2030s. Over its life SPO will execute repeated passes over both poles, with extended high-latitude observation windows totaling more than 1,000 days, enabling seasonal and cycle-dependent studies of polar magnetism and outflow.

Instruments and Measurements

To address its science goals, SPO will carry a combined suite of remote-sensing and in-situ instruments. Remote sensors include a Magnetic and Helioseismic Imager (MHI) for vector magnetic fields and surface flows, an Extreme Ultraviolet Telescope (EUT) and X-ray Imaging Telescope (XIT) to capture coronal heating and dynamics, a visible-light coronagraph (VISCOR) and a very large angle coronagraph (VLACOR) to image the outer corona and track solar wind streams to ~45 solar radii at 1 AU. The in-situ payload will feature a fluxgate magnetometer and particle detectors to sample fields, protons, electrons and heavy ions directly above polar regions.

By combining imaging of polar coronal structure with direct wind sampling and magnetic-field mapping, SPO aims to link the processes that generate and accelerate solar wind to the large-scale magnetic topology and to changes in the global dynamo.

Synergy with the Solar Fleet

SPO will not operate alone. It is expected to work as part of a multi-spacecraft solar network including STEREO, Hinode, SDO, IRIS, ASO-S, Solar Orbiter, Aditya-L1, PUNCH, and forthcoming L5 observatories such as ESA’s Vigil and China’s LAVSO. Together this ensemble will provide near-global, near-continuous coverage of the Sun — a 4π view — for the first time. SPO’s polar vantage fills a critical observational gap, enabling stereoscopic imaging and multi-point plasma measurements that refine three-dimensional heliospheric models.

Scientific and Practical Implications

A sustained polar perspective will have broad scientific and operational benefits. Improved knowledge of how polar fields form and reverse will constrain dynamo models and potentially improve solar cycle prediction — a key input to long-term planning for satellites and power-grid resilience. Clarifying fast wind sources and acceleration mechanisms will improve heliospheric models used in space weather forecasting and mission planning, affecting spacecraft design and astronaut safety. Finally, better tracking of CME propagation from an overhead polar viewpoint will reduce uncertainties in arrival time and impact estimates at Earth and throughout the inner solar system.

Expert Insight

"High-latitude observations are the missing piece in our understanding of how the Sun’s global magnetic field is assembled and redistributed," says Dr. Elena Martínez, a solar physicist familiar with polar mission planning. "SPO’s combination of continuous polar imaging and local sampling of the wind will let us directly test whether small-scale reconnection or wave heating dominates wind acceleration above coronal holes. That has huge implications for both basic physics and space weather prediction."

Related Technologies and Future Prospects

Reaching and operating at high solar latitudes pushes spacecraft navigation, thermal control and communications technologies. Gravity-assist trajectories require precise navigation and long cruise phases; higher inclinations may need innovative propulsion or sail concepts for faster transit. Onboard instrumentation must handle long-duration exposure to the heliospheric environment and provide stable, high-resolution measurements from changing solar distances.

Looking forward, SPO and similar missions could enable a new class of comparative heliophysics: studying how polar dynamics influence not only the Sun’s immediate surroundings but the broader solar system environment. As crewed and robotic missions venture beyond low Earth orbit, understanding the heliosphere’s structure and variability will become ever more important for mission planning and astronaut safety.

Conclusion

The Sun’s poles are more than remote curiosities: they are central to the processes that generate the solar magnetic cycle, launch the fast solar wind, and modulate space weather that affects Earth and technological assets across the heliosphere. The Solar Polar-orbit Observatory aims to deliver the polar observations necessary to answer long-standing questions about dynamo action, wind acceleration, and CME propagation. By filling a critical observational gap and partnering with the existing solar fleet, SPO could transform both our scientific understanding of the Sun and our practical ability to predict and mitigate space weather.

Source: scitechdaily

.webp)

Leave a Comment