7 Minutes

The Moon’s largest impact basin, the South Pole–Aitken (SPA), has just revealed a surprising detail about how it was formed — and that twist could give astronauts a direct view into the Moon’s deep interior. New analysis of SPA’s shape and chemistry suggests the ancient collision came from the north, not the south, and that the southern rim targeted by Artemis missions may host material excavated from far below the crust.

A fresh look at an ancient scar

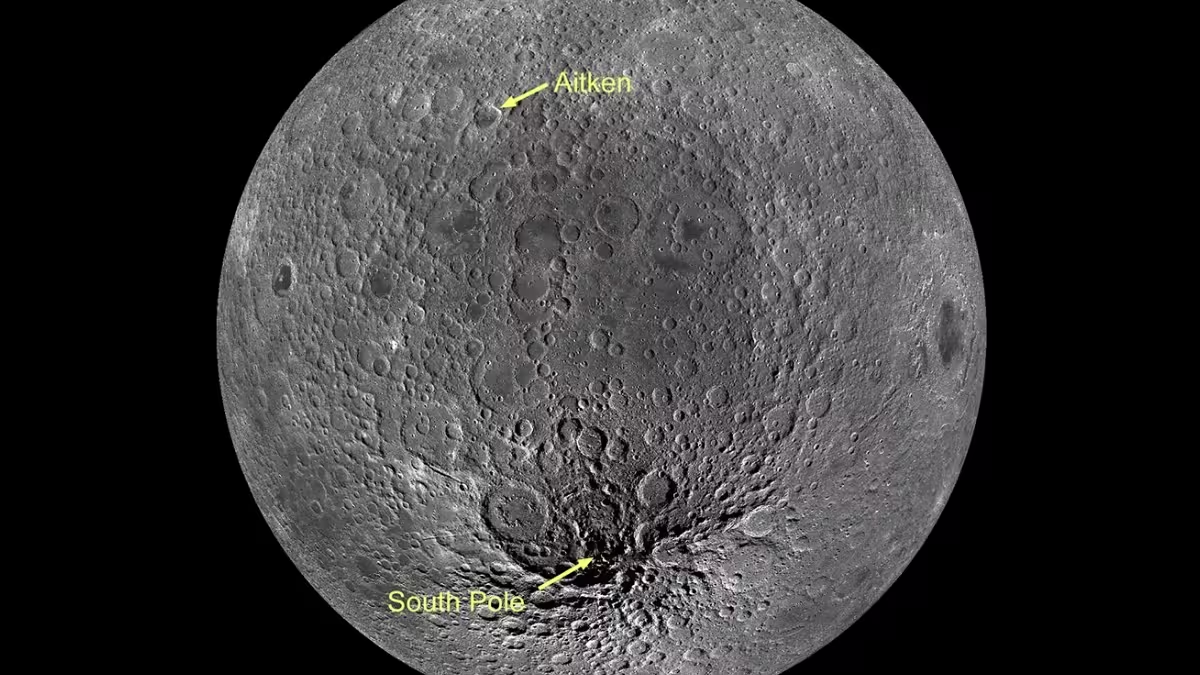

The Moon is tidally locked to Earth: it rotates once on its axis in the same time it takes to orbit our planet, which is why we always see nearly the same face. On the hemisphere that faces away lies the colossal South Pole–Aitken basin, an impact feature that stretches roughly 1,930 km north–south and about 1,600 km east–west. Formed around 4.3 billion years ago by a massive, glancing asteroid strike, SPA is one of the Solar System’s oldest and largest accessible windows into planetary interiors.

The Moon's largest impact feature, the South Pole–Aitken basin, is so named because it stretches between Aitken crater and the south pole. (NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University)

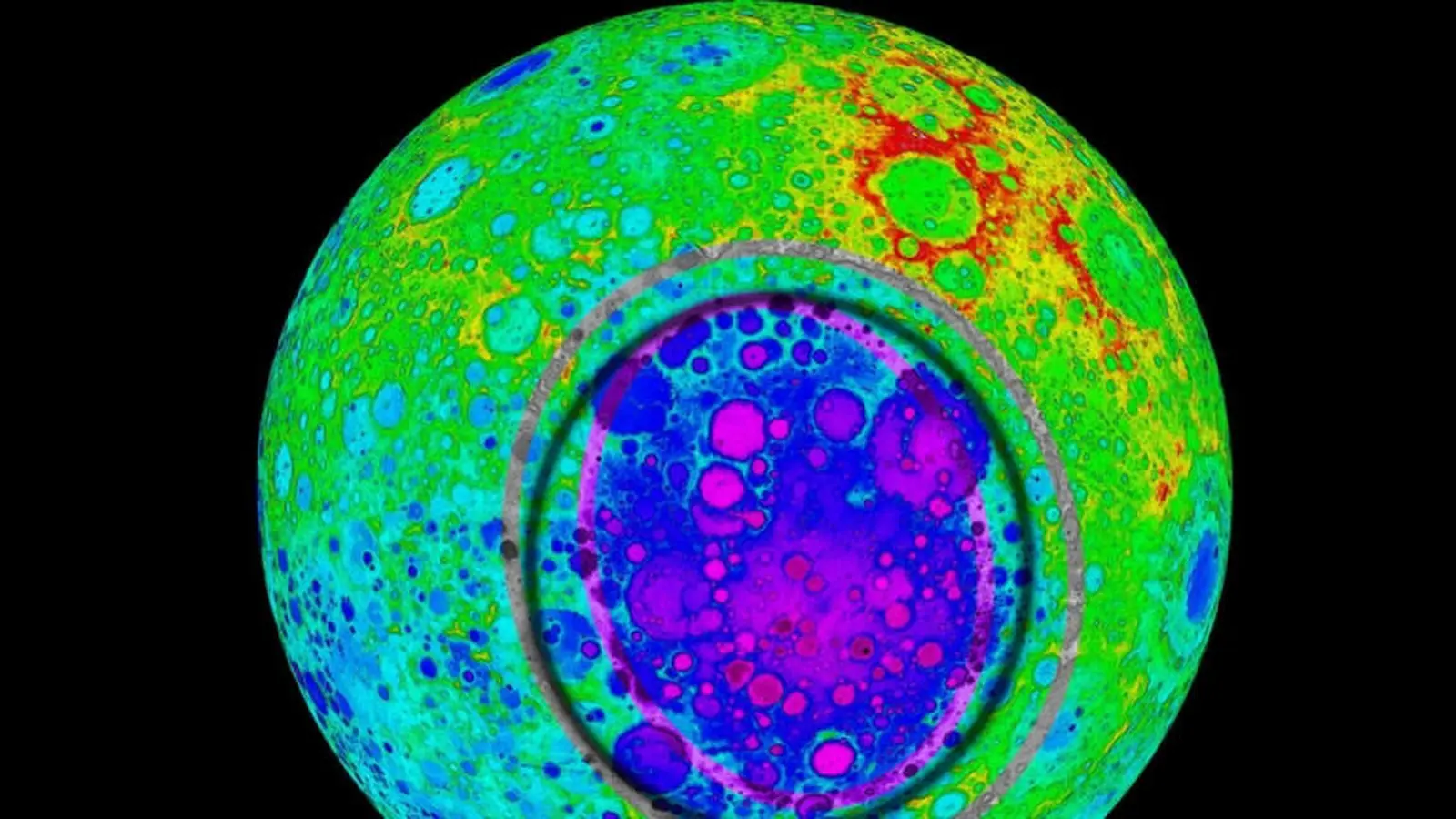

Researchers led by Jeffrey Andrews‑Hanna at the University of Arizona revisited the basin’s geometry and found a subtle but important asymmetry: SPA narrows toward the south. Across the Solar System, very large impact basins commonly show a teardrop shape oriented in the downrange direction of the incoming impactor. Prior work had assumed SPA’s narrow end pointed north, implying a south-to-north impact. The new analysis reverses that interpretation: SPA’s narrow end is to the south, indicating the asteroid came from the north.

Why impact direction matters for lunar samples

Impact mechanics don’t distribute excavated rocks evenly. In a low-angle, oblique collision, the downrange (narrow) end of a basin typically receives a deep blanket of ejecta — material scoured from great depths and then redeposited. The uprange end, by contrast, tends to be less buried and can expose deeper source rocks at the rim.

Craters Messier (left) and Messier A (right) on the Moon, in Mare Fecunditatis captured by Apollo 11. A great example of craters formed by low angle-impactors (NASA)

This geometry has immediate consequences for Artemis: because the impact likely arrived from the north, the southern rim is in the uprange zone. That makes the southern rim a prime sampling site where astronauts could collect material that originated deep in the lunar interior — essentially a cut that troubleshoots the need for deep drilling.

KREEP, crust thickness, and a lopsided Moon

To understand the full significance, we need a quick primer on lunar chemistry. Early in its history the Moon was blanketed by a global magma ocean. As the ocean cooled, minerals crystallized and separated by density: heavy phases sank to form the mantle, light minerals floated to build the crust. But some elements — potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus — remained in the last, most evolved liquids. This potassium-rare-earth-phosphorus assemblage is known by the shorthand KREEP.

KREEP is radiogenic and generates heat; its concentration on the near side is thought to have driven the intense mare volcanism that formed the dark plains visible to Earth. The far side, by contrast, stayed thicker-skulled and heavily cratered, with far fewer volcanic plains.

One longstanding puzzle: why did KREEP end up asymmetrically concentrated on the near side? The new SPA analysis supports a model where the far-side crust became substantially thicker early on. That thickening squeezed residual magma — enriched in KREEP — toward the thinner near side, leaving only patchy KREEP deposits beneath some far-side crust. The SPA impact appears to have sliced through one of these boundary zones.

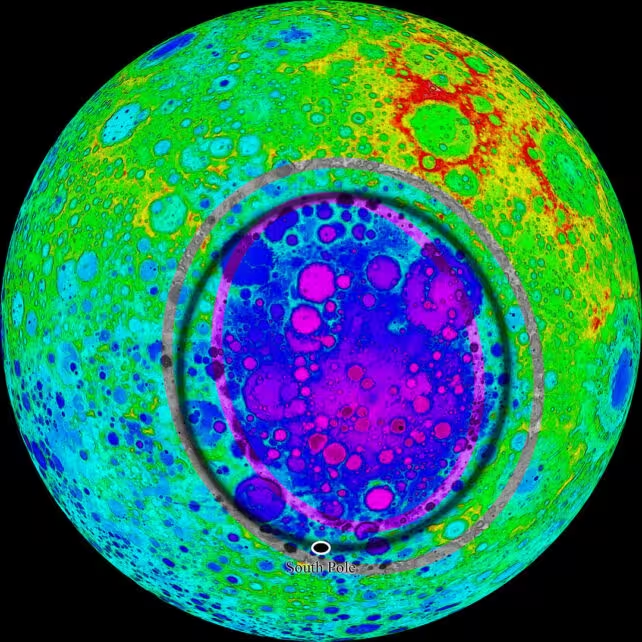

South pole Aitken basin on the Moon, from JAXA's Kaguya data. Viewed at -45 degrees. The black ring is an old approximation; the elliptical purple and grey rings trace the inner and outer ring of the crater (Ittiz/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Remote sensing data reveal a chemical asymmetry across SPA: the western flank shows elevated thorium — a tracer for KREEP — while the eastern side does not. That contrast is consistent with the basin cutting across the transition between KREEP-rich pockets and more typical far-side crust. If Artemis teams collect and return samples from the southern rim, laboratory analysis on Earth could directly test whether the basin excavated KREEP-rich or deeper mantle material.

Why Artemis landing sites are a geological jackpot

NASA’s Artemis architecture aims to return humans to the lunar surface and bring samples back to Earth. Landing near SPA’s southern rim could be especially rewarding: astronauts on EVAs could collect varied lithologies — impact melt, melt breccias, and mantle-derived rocks — that together tell a tightly constrained story of the basin-forming event and the Moon’s early differentiation.

Artemis I successfully launched from the Kennedy Space Center on 16 November 2022. (Bill Ingalls)

Those returned specimens would allow geochemists to measure KREEP abundances, isotopic clocks, and shock histories — transforming theoretical models of crustal growth, magma ocean evolution, and hemispheric asymmetry into testable science. In other words: samples from SPA could finally answer how the Moon evolved from a molten sphere to the two-faced world we know today.

Expert Insight

“Finding that the impact likely approached from the north reframes SPA as not just an ancient scar, but as a natural drill bit that exposed deeper material,” says Dr. Elena Vargas, a lunar geophysicist at the fictional Planetary Materials Lab. “If Artemis crews collect rocks from the southern rim, we may obtain the first direct samples of the Moon’s lower crust or even upper mantle — material that has been inaccessible since the basin formed over four billion years ago.”

That combination of updated basin geometry, remote geochemical signatures, and forthcoming human missions makes SPA one of planetary science’s most promising targets. As sample return plans move from blueprints into hardware and human crews prepare to walk the lunar far side’s greatest depression, the Moon may soon yield answers that have been locked in rock since the Solar System’s formative era.

This research was published in Nature.

Artemis I successfully launched from the Kennedy Space Center on 16 November 2022. (Bill Ingalls)

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

hmm is this even true? could the shape be misread from old data or imaging bias? need samples asap, idk

astroset

wait, so the asteroid came from the north? mind blown. If Artemis finds mantle rocks that'll be epic, but skeptical lol

Leave a Comment