6 Minutes

Spraying reflective particles into Earth’s upper atmosphere—an idea known as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI)—has re-emerged as a provocative short-cut to cool the planet. But a new analysis from aerosol researchers at Columbia University says the approach is far from a simple fix: real-world physics, manufacturing limits, and geopolitics make SAI risky, technically challenging, and practically infeasible at the scale often imagined.

Why scientists considered 'dimming' in the first place

SAI is based on a familiar natural experiment: large volcanic eruptions loft sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere and temporarily reduce global temperatures by scattering sunlight back into space. That volcanic cooling, observed after eruptions such as Mount Pinatubo in 1991, convinced some researchers that carefully controlled aerosol injections could offset human-caused warming.

Computer models have shown that, under ideal conditions, seeding the stratosphere with reflective particles could lower global average temperatures. The catch: models typically assume the perfect particle, released in precisely the right place, at exactly the right cadence. When researchers examined the logistics behind turning those idealized scenarios into an operational program, they found many hard limits.

From models to reality: hard limits and messy physics

“There are a range of things that might happen if you try to do this — and we're arguing that the range of possible outcomes is a lot wider than anybody has appreciated until now,” says V. Faye McNeill, an atmospheric chemist and aerosol scientist at Columbia University. Miranda Hack, an aerosol scientist who led the new analysis, adds that materials, supply chains, and particle behavior have been underappreciated in many previous studies.

A key technical dilemma is particle size and behavior. For aerosols to scatter sunlight efficiently they must be within a narrow size range—typically submicron. But at those scales many mineral particles tend to coagulate, or clump together, forming larger aggregates that are much less effective at reflecting sunlight. That physical chemistry effect reduces the cooling per unit mass and changes how long particles remain aloft.

Delivery altitude matters too. Launching aerosols higher into the stratosphere will keep them aloft longer, but it also raises the risk of chemically damaging the polar ozone layer. Deploying at mid-latitudes may redistribute heat in ways that alter regional climate patterns, potentially harming precipitation regimes and polar climate processes. In short: where you inject is as consequential as what you inject.

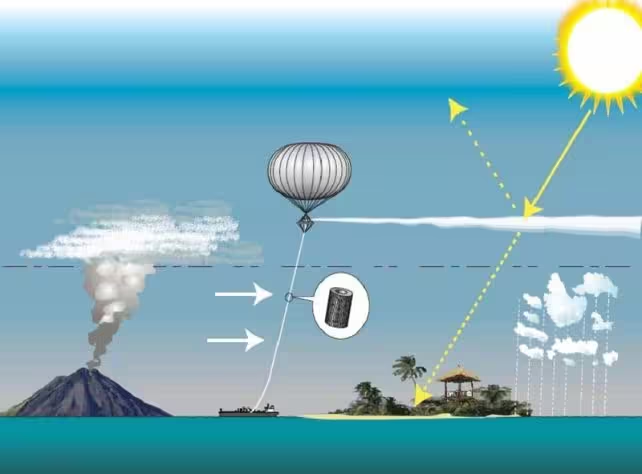

A diagram illustrating how SAI is supposed to work. High-altitude balloons (pictured here) have been considered, along with aircraft, as a method of delivering aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect the Sun's rays. (Hughhunt/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Material shortages and strained supply chains

Another blind spot in many SAI studies is the assumption that the required materials are abundant and easy to produce. Some proposals have even floated exotic ideas—diamond or zircon dust—because of their reflective properties. But the Columbia team points out that the annual mass of aerosol material required for some SAI scenarios would match or exceed current global production of those minerals. In practice, that makes such materials unrealistic.

More common candidates—sulfur or lime—are more plentiful, but manufacturing and transport at the scale needed for repeated, long-term injections would stress supply chains and energy systems. Producing, processing, and delivering millions of tonnes of material each year introduces carbon, resource, and economic costs that weaken the case that SAI is a simple or low-impact intervention.

Volcanic eruptions, like this 2015 eruption of Calbuco in Chile, release aerosols such as sulfur dioxide that can slightly cool the atmosphere for short periods. (NASA Earth Observatory)

Governance: why politics matters as much as physics

Even if engineers could solve particle chemistry and industrial bottlenecks, governance represents another formidable barrier. The researchers argue the “optimal” deployment would require a single, internationally coordinated authority to manage where, when, and how aerosols are released. That centralized governance matters because uneven or uncoordinated releases could create regional cooling disparities, changing monsoon cycles or polar heat transport in ways that might advantage some nations while harming others.

But centralized global governance for a program with such geopolitical implications is unlikely. The more realistic alternative—multiple independent actors or national programs—risks patchy implementation, conflicting objectives, and shorter-lived projects that fail to achieve the modeled benefits and exacerbate uncertainties.

What the models miss: uncertainty and the 'worst-case' envelope

Climate models remain essential tools for exploring SAI, but the new paper stresses that many simulations are ‘‘idealized’’ and do not capture supply-chain constraints, particle clumping, or governance fragmentation. These limitations push real-world outcomes away from the neat scenarios often shown in academic studies.

“A more complete understanding of 'worst-case' tropospheric climate impacts through global climate model runs that simulate aggregate injection might better contextualize these results,” the authors write, arguing for research that includes practical constraints to produce a clearer risk–risk comparison for policymakers.

Implications for climate policy and research priorities

The Columbia analysis does not deny that solar geoengineering could, in principle, lower temperatures. Instead it reframes the discussion: SAI is not a low-effort stopgap but a program that would entail long-term commitments, complex supply chains, and international governance—along with real physical risks, including ozone depletion and uneven regional impacts.

For decision-makers, the paper sends a clear message: invest in better climate mitigation and adaptation now, because large-scale geoengineering is neither a free nor a simple insurance policy. At the same time, the authors advocate targeted research on particle physics, supply feasibility, and international governance frameworks so that any future discussions are grounded in operational realism rather than idealized models.

Expert Insight

“Solar geoengineering raises powerful technical and ethical questions,” says Dr. Andrea Morales, a fictional atmospheric scientist formerly with a NASA-affiliated climate program. “From an engineering perspective, the practicalities of producing and delivering billions of kilograms of material every year are often overlooked. From a policy perspective, once you alter the global energy balance, it becomes a geopolitical issue: who decides the thermostat?”

Such commentary underlines a wider point: SAI touches on hard science, industrial capacity, and global diplomacy simultaneously. Any future exploration must be multidisciplinary, transparent, and subject to rigorous public and international scrutiny.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Armin

Wow didnt expect the mineral shortage angle. Makes SAI feel less sci-fi quick fix and more like a logistics nightmare. Cut CO2 instead, honestly

labcore

Models sound neat but real world physics and supply chains are brutal. Is spraying millions of tons even practical? ozone damage, regional losers, who decides? if thats real then…

Leave a Comment