7 Minutes

Windows are essential for daylight and views, but they are also one of the largest sources of heat loss and gain in buildings. Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have developed a nearly transparent insulating material called MOCHI that promises to slow heat transfer through glass without blocking light — potentially transforming how we heat, cool, and design energy-efficient buildings.

What is MOCHI and why it matters

MOCHI stands for Mesoporous Optically Clear Heat Insulator. It is a silicone-based gel engineered to contain a vast network of microscopic air channels, so fine that air makes up more than 90% of the material’s volume. That internal architecture lets MOCHI combine two properties that rarely appear together: excellent thermal insulation and high optical clarity.

A key advantage is visual. Unlike many insulating materials that scatter light and blur views, MOCHI transmits nearly all visible light while reflecting only about 0.2% of incoming light. For building owners and designers, that means you could add insulation to windows without losing daylight, solar views, or the visual connection to the outside.

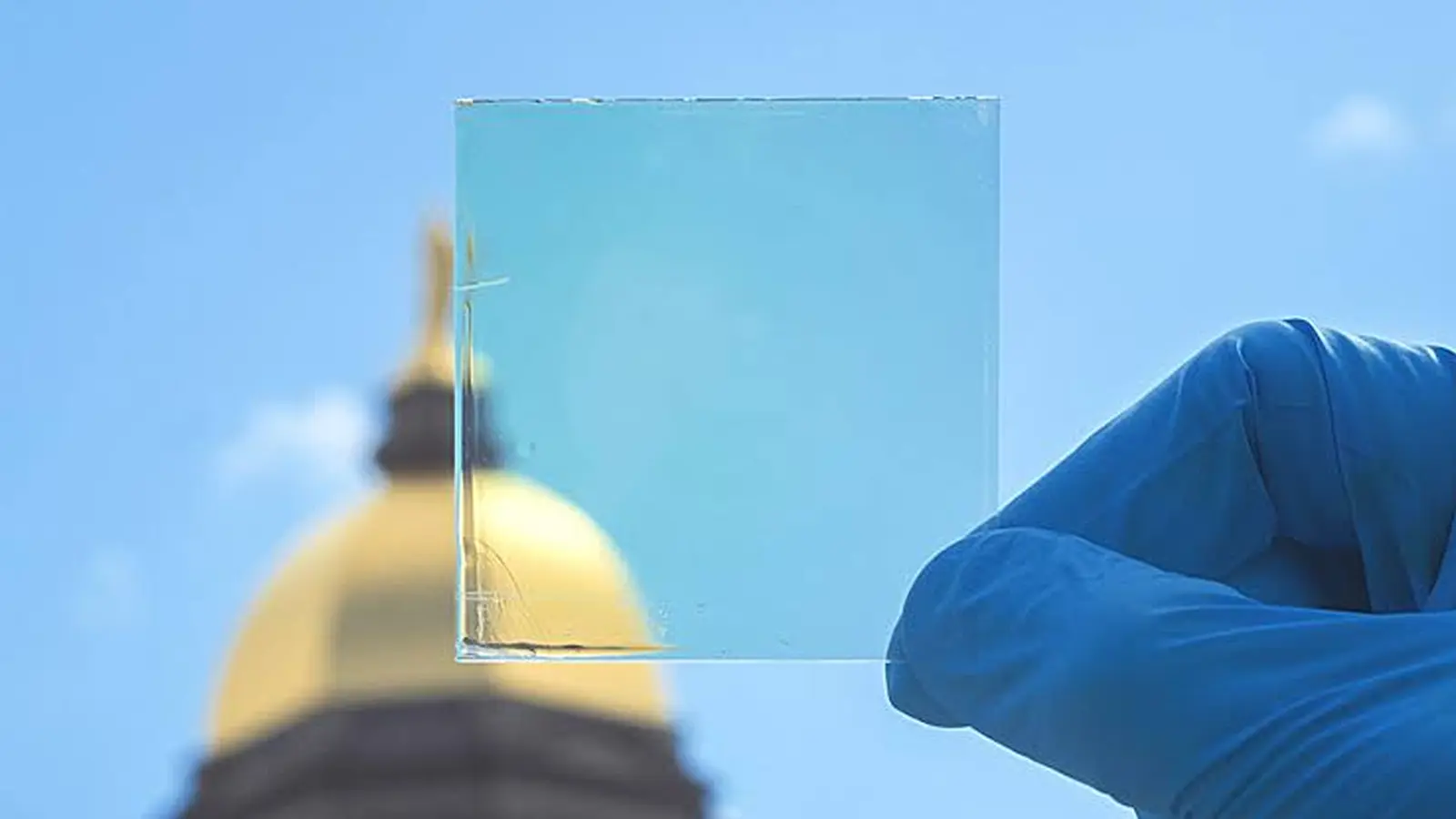

Abram Fluckiger holds up a sample panel square that has five sandwiched layers of a new material nearly transparent insulation material called MOCHI, which was designed buy CU Boulder researchers in physics professor Ivan Smalyukh’s lab.

How the material is made and how it blocks heat

At the core of MOCHI’s performance is control of pore size and arrangement. The research team uses surfactant molecules in a liquid solution to form threadlike templates. Silicone molecules coat those threads and then the researchers remove the surfactant and replace it with air, leaving behind an intricate silicone skeleton with extremely small air-filled channels. Smalyukh described the remaining channel network as ‘‘a plumber’s nightmare.’’

Those tiny channels put the gas inside in what physicists call a mesoporous regime: pores are comparable to, or smaller than, the mean free path of air molecules. Instead of colliding freely with each other and transferring energy (heat), gas molecules inside each pore repeatedly strike the channel walls. That limits conductive heat transfer through the material in much the same way that thermal insulation works in aerogels — but with one big difference: MOCHI is engineered to minimize light scattering, so it remains exceptionally clear.

To illustrate the insulating strength, the team reports that a 5-mm MOCHI sheet can withstand a flame held against it without conducting enough heat to cause burns on the other side. That dramatic demonstration underlines how effective a highly porous, carefully structured material can be at slowing heat flow.

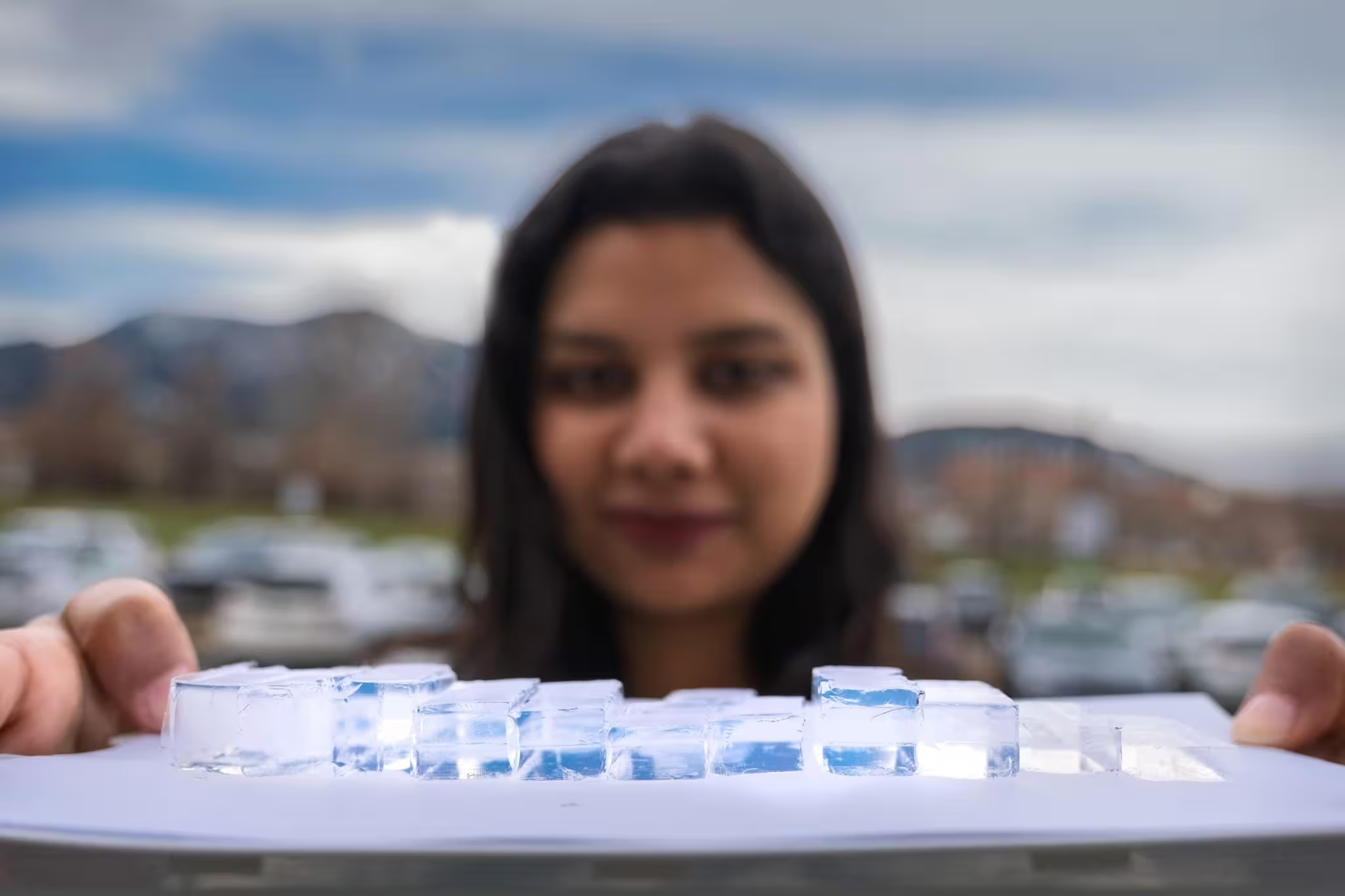

Shakshi Bhardwaj holds up blocks in different sizes of a new material nearly transparent insulation material called MOCHI, which was designed buy CU Boulder researchers in physics professor Ivan Smalyukh’s lab.

Windows, buildings, and the scale of the problem

Buildings consume roughly 40% of global energy production, and a sizable fraction of that energy is exchanged through windows. In winter, warm interior air escapes; in summer, sunlight and outside heat enter through glass. Traditional strategies to reduce that exchange include double or triple glazing, low-emissivity coatings, and insulated window frames — all effective to varying degrees but sometimes limited by cost, weight, or reduced daylight.

MOCHI targets a gap: an interior-applied panel or thin sheet that can be added to existing windows to improve thermal resistance while preserving transparency. If scalable, such an approach could reduce heating and cooling demand across residential and commercial buildings, lowering energy bills and carbon emissions without compromising daylight or views.

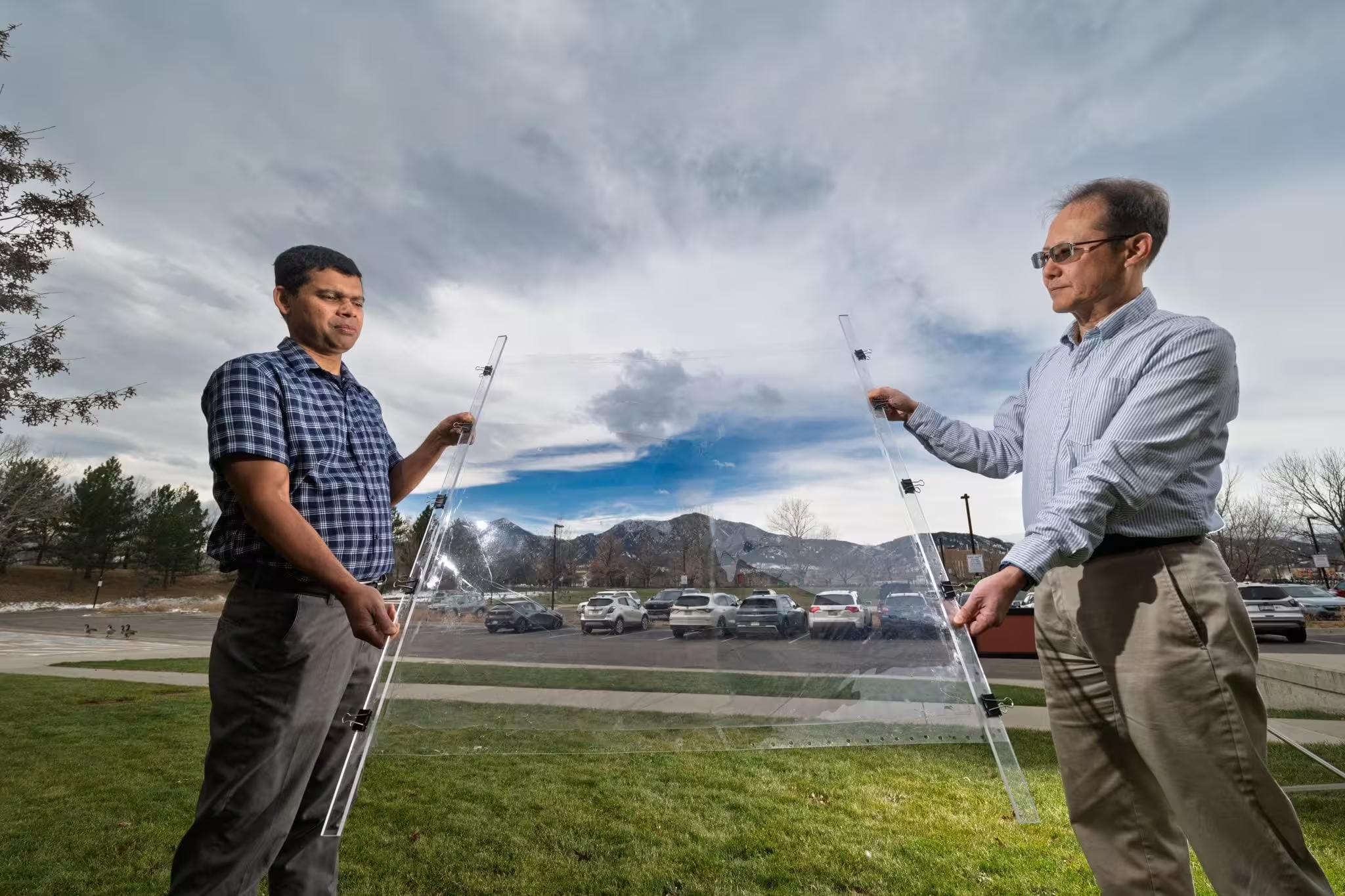

Eldho Abraham, left, and Taewoo Lee, right, hold up a new window insulation material called MOCHI affixed to a thin sheet of plastic, which was designed by CU Boulder researchers in physic professor Ivan Smalyukh’s lab.

MOCHI versus aerogels and other insulation

Aerogels are the best-known ultralight insulators and are used in niche applications including NASA’s spacecraft components. However, aerogels often appear cloudy because their pores scatter visible light. The CU Boulder team deliberately structured MOCHI’s pores to reduce scattering, achieving clarity closer to conventional glass while preserving thermal performance closer to advanced porous insulators.

MOCHI’s material chemistry — a silicone gel framework — also brings practical advantages: the raw materials are relatively inexpensive, and the product can be formed as thin sheets or thicker panels to fit different uses. That said, the current fabrication requires slow, careful laboratory work. The authors of the Science paper emphasize that scaling production and streamlining manufacturing will be essential before MOCHI reaches the marketplace.

Potential applications beyond windows

While windows are the most obvious target, MOCHI’s combination of clarity and thermal resistance opens other possibilities. The team suggests applications that harvest or manage solar heat: transparent thermal collectors, insulated skylights, or window-mounted systems that capture sunlight and convert some energy into heat for water or space heating. In cloudy conditions, partial solar capture combined with improved insulation could still yield measurable energy savings.

The researchers also note potential for use in electronics enclosures, optical instruments, and anywhere a transparent thermal barrier is valuable. Because MOCHI reflects only a tiny fraction of visible light, it could be integrated into façade systems and retrofit products without dramatically altering building appearance.

Challenges on the path to commercialization

Despite promising lab results, there are hurdles. Current synthesis is time-consuming and optimized for small samples; long-term durability and UV stability under real-world weather must be validated; and manufacturing processes will need to be adapted for large-area, cost-effective production. Nevertheless, the team is optimistic that process simplifications and roll-to-roll or castable approaches could eventually make MOCHI a practical retrofit or factory-installed option.

Expert Insight

"MOCHI demonstrates how microstructure design can reconcile two competing demands — optical clarity and thermal resistance," says Dr. Maya Ortega, a materials scientist who studies porous insulators (fictional expert). "If the team can translate lab methods into continuous manufacturing, this could be a game-changer for retrofit strategies in both existing buildings and new construction. The key will be durability and cost at scale."

Ivan Smalyukh, senior author and professor of physics at CU Boulder, framed the goal simply: "No matter what the temperatures are outside, we want people to be able to have comfortable temperatures inside without having to waste energy." The paper reporting MOCHI appeared in Science on December 11, signaling peer-reviewed validation of the core concept while leaving the engineering and commercialization work ahead.

Researchers and building professionals will be watching how MOCHI progresses from striking lab demonstration to practical product. If it crosses that bridge, the material could allow clearer, more energy-efficient windows that keep views and daylight — and greatly reduce the energy needed to heat and cool buildings.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

atomwave

Is this even true? Seems too good: clear AND insulating. what's the catch, cost, lifespan, manufacturing scale? also, how does it stick to old frames?

labcore

wow this MOCHI thing sounds like sci-fi but real, if it scales windows could totally change. curious about UV aging tho, hope they test it long term

Leave a Comment