6 Minutes

Anxiety might not be driven solely by neurons. New research in mice suggests a tug-of-war between two distinct groups of brain immune cells — microglia — can flip anxious behavior on or off. This discovery reframes how scientists think about the biological roots of anxiety and points toward immune-focused strategies for future treatments.

Researchers discovered that two competing groups of brain immune cells help determine anxiety levels. The balance between these cells may explain why anxiety can spiral out of control.

Immune cells, not just neurons: a surprising place to look

For decades, anxiety research has focused on neuronal circuits, neurotransmitters and synapses. But the brain also contains its own resident immune cells — microglia — that monitor and maintain neural tissue. These cells prune synapses, respond to injury and shape inflammatory signals. The University of Utah team found that two microglial subpopulations behave like opposing controls: one acts as an "accelerator," promoting anxiety-like behaviors, while the other functions as a "brake," suppressing them.

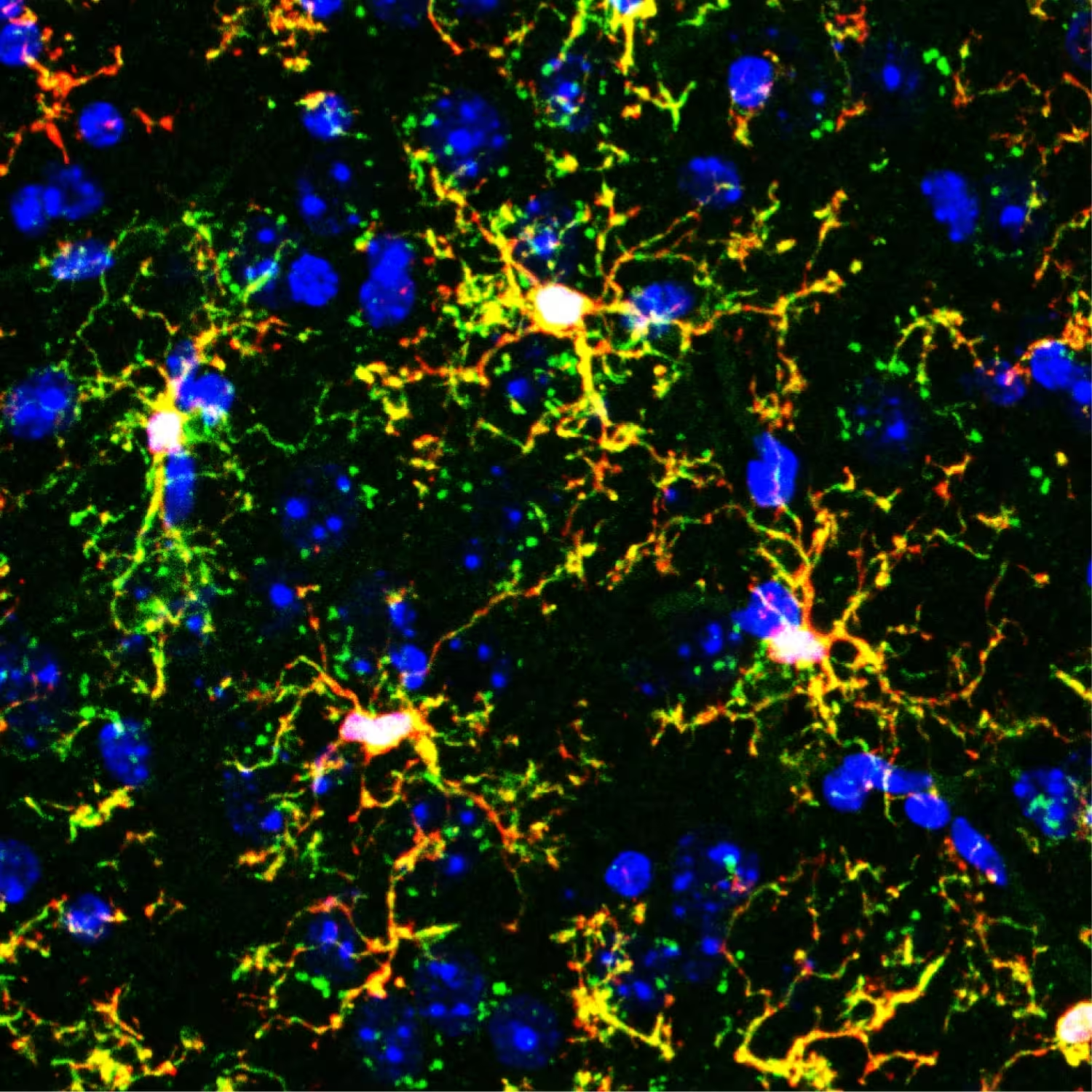

Fluorescent microscope image of transplanted microglia (branching yellow shapes) in a mouse brain. Red marks gene-edited transplanted microglia, green marks immune cells called macrophages, and blue marks cell nuclei.

How the researchers untangled the microglial tug-of-war

The study, reported in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, began with a puzzling observation. When researchers selectively disrupted a subgroup of microglia known as Hoxb8 microglia, mice developed anxiety-like behaviors: increased grooming and avoidance of open spaces. Yet when all microglia were suppressed at once — including both Hoxb8 and non-Hoxb8 cells — the animals behaved normally.

That contradiction suggested the two populations might have opposite roles. To test this, investigators used a bold experimental strategy: they created mice lacking microglia entirely, then transplanted back specific microglial populations to see how each shaped behavior.

Accelerators and brakes, isolated

When mice received only non-Hoxb8 microglia, they showed clear signs of heightened anxiety — the behavioral equivalent of flooring the gas pedal. Excessive grooming and aversion to open areas became pronounced. Conversely, mice that received only Hoxb8 microglia remained calm, indicating a dominant inhibitory influence. Importantly, mice with both populations restored a balanced behavior: the brake countered the accelerator, preventing chronic anxiety responses.

These results led senior author Mario Capecchi, PhD, to conclude that the two microglial populations set the appropriate level of anxiety in response to environmental conditions. “Together, they set just the right levels of anxiety in response to what is happening in the mouse’s environment,” Capecchi said.

Donn Van Deren, PhD, lead author on the study

Why this changes how we think about anxiety biology

Most psychiatric drugs target neuronal signaling pathways. The new findings suggest immune cells within the brain are not passive bystanders but active regulators of behavior. If similar microglial subtypes and circuits exist in humans — and the team notes humans appear to have comparable microglial diversity — then some forms of anxiety could stem from imbalances in these immune populations rather than from classic neurotransmitter defects.

That doesn’t mean microglia replace neurons as the central actors in mood regulation, but it adds a new layer: immune–neural interactions that fine-tune behavioral responses. It also provides a plausible mechanism for why anxiety can abruptly escalate in some people — a loss of braking microglia or an overactive accelerator population could tip the system into persistent hypervigilance and avoidance.

Potential paths for therapies and diagnostics

Translating this into human treatments will take time. But the conceptual implications are large. Therapies could aim to bolster the brain’s braking microglia, suppress overactive accelerator microglia, or shift signaling between these subtypes. Approaches might include small molecules that change microglial function, targeted immunotherapies, or even cell-based strategies in the distant future.

“We’re far from the therapeutic side,” said Donn Van Deren. “But in the future, one could probably target very specific immune cell populations in the brain and correct them through pharmacological or immunotherapeutic approaches. This would be a major shift in how to treat neuropsychiatric disorders.”

Scientific context and open questions

- The mechanisms by which Hoxb8 and non-Hoxb8 microglia exert opposite effects remain to be clarified: are they secreting distinct signaling molecules, pruning different synapses, or engaging different neural circuits?

- How do environmental stressors and developmental factors influence the balance between these microglial populations?

- Can peripheral immune events (infection, inflammation) reshape the microglial accelerator–brake balance and thereby trigger or worsen anxiety?

Addressing these questions will require molecular profiling, circuit mapping and human tissue studies to confirm parallels between species.

Expert Insight

"This study reframes anxiety as an emergent property of neural and immune crosstalk, not solely a neuronal misfire," says Dr. Laura Mendes, a fictional neuroimmunologist and science communicator. "If we can map which synapses each microglial subtype targets and how they modulate neurotransmitter systems, we might design highly specific interventions that restore balance with fewer side effects than broad-acting drugs."

Mario Capecchi, PhD, senior author on the study, annotates a whiteboard with diagrams of microglia in the brain.

What this means for patients and researchers

For people living with anxiety disorders, these findings are an early but hopeful step. They suggest new biomarkers and treatment targets outside the traditional neurotransmitter framework. For researchers, the study opens a promising line of inquiry at the intersection of immunology, genetics and behavioral neuroscience.

As the field moves forward, combining genetic tools, single-cell profiling and behavioral assays will be key to turning this conceptual advance into practical diagnostics or therapies. Until then, the discovery stands as a reminder that the brain’s immune system plays a dynamic, and sometimes decisive, role in shaping how we feel and react.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

Whoa! brain immune cells calling the shots? that's wild. Imagine targeted treatments, but also kinda scary, tinkering with microglia could have big side effects…

labcore

hmm so microglia might flip anxiety on/off? if true this changes the map, but mice arent humans, need more proof. still, cool idea kinda mindblown

Leave a Comment