5 Minutes

People often chalk up forgetfulness to "just getting older." But what if aging is less a single culprit and more a chorus of slow, interacting changes across the brain?

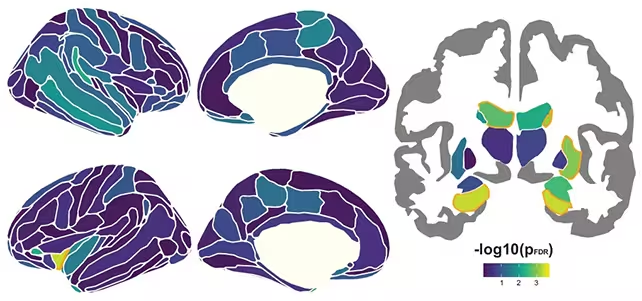

Scientists led from the University of Oslo have pushed that question beyond anecdote by pooling a massive collection of clinical data: thousands of healthy volunteers, more than 10,000 MRI scans and well over 13,000 cognitive tests. The result is one of the clearest, most detailed pictures yet of how structural brain changes over decades relate to episodic memory — the faculty that lets you recall events, places and moments.

The study and the data

The analysis combined records from 3,737 cognitively healthy participants tracked across multiple long-standing research cohorts. That scale matters. Small studies can hint at patterns; this one stitches dozens of cohorts together to reveal how brain anatomy and memory performance co-evolve across the adult lifespan.

Unsurprisingly, the hippocampus — long known as a memory hub — stood out. But the headline shouldn’t be "hippocampus only." Shrinkage in multiple brain regions correlated with worse episodic memory, and those correlations strengthened with advancing age. In other words, brain volume loss becomes more consequential for memory as people move past about 60 years old, and changes in many regions, not a single hotspot, shape that decline.

Genetics also play a role. Carriers of the APOE ε4 allele — a variant linked to higher Alzheimer's risk — showed faster tissue loss and steeper memory decline on average. Yet the overall trajectory across the whole sample was consistent: the same anatomical processes were at work, only accelerated in APOE ε4 carriers. As neurologist Alvaro Pascual-Leone noted, "By integrating data across dozens of research cohorts, we now have the most detailed picture yet of how structural changes in the brain unfold with age and how they relate to memory."

Anatomy of decline and what it means

So what should we take from this? First, memory loss in later life is seldom the product of a single failing region. It reflects a broad biological vulnerability: a pattern of gradual atrophy that accumulates over decades. Second, timing matters. The same degree of regional shrinkage seems to matter more after midlife, implying that small losses earlier on can cascade into bigger functional consequences later.

That has practical consequences for research and therapy. Treatments aimed at preserving memory are unlikely to succeed if they target only one structure. Effective interventions will probably need to address multiple brain networks — protecting tissue, supporting synaptic health, and reducing inflammation or vascular damage where relevant. The study’s authors suggest that early intervention will be more beneficial than waiting until clear cognitive decline appears.

There is a sliver of encouraging news. Because the patterns are broadly shared between people with and without APOE ε4, many therapeutic strategies could benefit both groups. In other words: the same underlying mechanisms appear to be at play, just at different speeds.

Future directions and tools

Large-scale MRI datasets like this one are a boon for predictive models of cognitive aging. Machine learning tools, combined with longitudinal imaging and repeated memory testing, could help identify individuals at higher risk years before symptoms emerge. That opens the door to precision prevention — personalized lifestyle or pharmacological strategies tuned to someone's anatomical trajectory.

Still, questions remain. What drives variation between individuals? How do vascular health, inflammation, lifestyle, and education intersect with genetics to shape these brain trajectories? And crucially: which interventions actually change the slope of decline rather than merely slowing a symptom?

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Reynolds, a cognitive neuroscientist and aging specialist, comments: "This kind of integrative work reframes how we think about memory loss. It's not an isolated failure but a system-level vulnerability. That shifts our focus from single-target drugs to multidimensional strategies — from vascular risk control and exercise to sleep health and targeted neuroprotection. Early assessment and sustained interventions could make a real difference decades down the line."

As researchers dig deeper into the biological pathways behind brain atrophy and episodic memory decline, the pathway to intervention becomes clearer: detect early, treat broadly, and tailor efforts to individual risk profiles. The hope is to change aging from an inevitable slide into forgetfulness into a process that can be managed and, in many cases, substantially delayed.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Marius

Is this for real? huge MRI sample, cool. but causation vs correlation? vascular health, education, lifestyle could explain a lot. need trials, pronto

datapulse

wow didnt expect memory loss to be such a chorus across the brain. kinda scary but hopeful if early action helps, need more on lifestyle tho

Leave a Comment